Everyone is a theologian, R. C. Sproul rightly observed. Anyone with ideas or beliefs about God is doing theology. It may be poorly considered, but it’s theology nonetheless.

By the same token, it might be said that everyone has an ecclesiology, a doctrine of the church. We all have beliefs or assumptions about what the church is, why it exists, and how it ought to function. Rarely do we pause, though, to think deeply about these things. Even among pastors, the incessant demands of ministry often pull us toward fixing urgent problems while neglecting larger questions. What does healthy pastoral ministry look like? What matters most in the life of my church? Am I shepherding God’s flock in a way that pleases him?

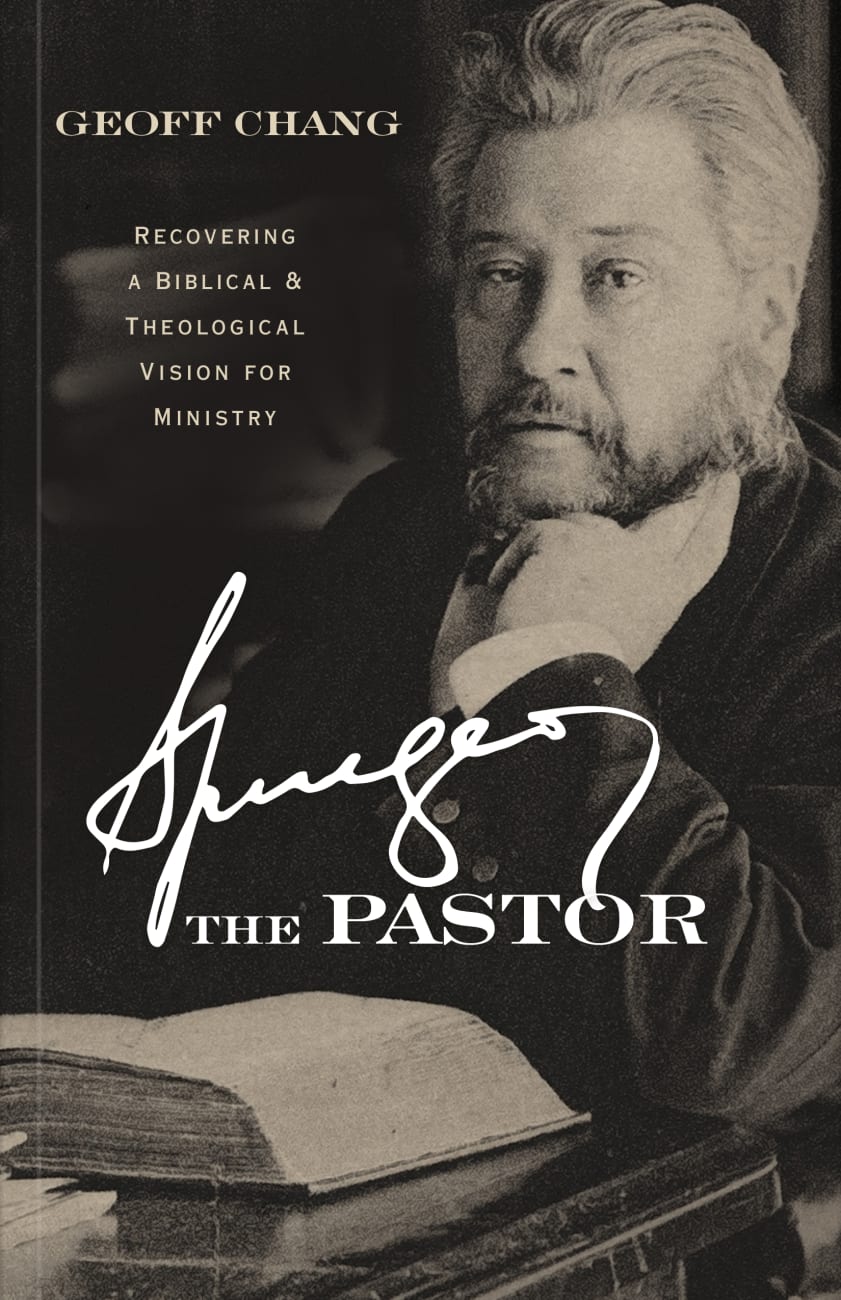

In Spurgeon the Pastor: Recovering a Biblical and Theological Vision for Ministry, Geoffrey Chang shows why the 19th-century Baptist expositor should be regarded as more than “the Prince of Preachers”—he should be studied as an example of a faithful pastor. Chang—assistant professor of church history and historical theology and curator of the Spurgeon Library at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary—contends there’s “no better model of faithful pastoral ministry and commitment to the local church” than Spurgeon (2).

Spurgeon the Pastor: Recovering a Biblical and Theological Vision for Ministry

Geoffrey Chang

Spurgeon the Pastor: Recovering a Biblical and Theological Vision for Ministry

Geoffrey Chang

In Spurgeon the Pastor, Geoff Chang, director of the Spurgeon Library at Midwestern Seminary, shows how Spurgeon models a theological vision of ministry in preaching, baptism and the Lord’s supper, meaningful church membership, biblical church leadership, leadership development, and more.

In 10 topical chapters, Chang considers various facets of Spurgeon’s ministry at the Metropolitan Tabernacle in London, ranging from church leadership and congregationalism to the ordinances and membership. He invites us to study Spurgeon as one who thought deeply about the local church and who therefore “remains a valuable conversation partner for pastors today” (5).

First Things First

We have a fascinating propensity to overcomplicate things. Just as Naaman couldn’t fathom that his leprosy would be healed by bathing in the appointed waters (2 Kings 5), we can have a lurking suspicion there must be more to church than a covenant community preaching the gospel and practicing the ordinances.

When we doubt the sufficiency of God’s appointed means for ordering his church, we begin to seek out every manner of man-made scheme to make up for what’s lacking. The result is churches who will try everything except the relatively few things most essential to a biblically healthy church. Is it possible that our never-ending church innovations and strategic ministry “breakthroughs” reveal a lack of faith in God’s own design for his church?

Spurgeon never tired of the simplest strategies, because he believed they were biblically warranted: corporate prayer, congregational singing, and the reading and preaching of God’s Word. He was convinced that people’s primary need is to hear the gospel—and that preaching is the primary means by which it happens.

Shepherding the Masses

None of this means a stripped-down, simplified approach is always best. Sunday-morning attendance at the Metropolitan Tabernacle numbered in the thousands, and weekly church life was remarkably busy. By his 50th birthday, Spurgeon’s congregation supported some 66 entities. The busyness wasn’t in spite of Spurgeon’s straightforward ecclesiology but a natural byproduct of it.

One of the more striking features of Spurgeon’s ministry is how his church was able to maintain meaningful church membership despite its large size and transient population. Spurgeon believed the church isn’t a building or a loose collection of people but a community of regenerate believers bound in covenant commitment. This was no abstract theory; it was a guiding principle.

One of the more striking features of Spurgeon’s ministry is how his church was able to maintain meaningful church membership despite its large size and transient population.

Over the course of his ministry, Spurgeon’s church took in 13,797 members and removed 9,281. The membership process wasn’t a matter of record keeping but pastoral engagement. Every meeting with a newcomer—and every conversation with an outgoing member—presented a chance to shepherd an eternal soul.

Church membership, some might assume, suggests exclusivity and inhibits growth. Others assume membership—if it must be employed—works only in smaller congregations. But Spurgeon discovered that the larger the church grew, the more critical an intentional membership process became. With thousands of attendees and scores of weekly visitors, for whom was Spurgeon spiritually responsible as a pastor? How was he to know who grasped the gospel and was committed to the church, and who was merely a nominal believer or casual observer? Church membership offered the answer.

Even though he shared the pastoral load with a plurality of elders, Spurgeon bore much of the burden of interviewing candidates for membership. In a sermon three decades into his ministry, he recounted a day “on which I lately saw 40 persons one by one, and listened to their experiences and proposed them to the church [for membership]” (120). Exhausting though it was, Spurgeon found a robust membership process indispensable to pastoral ministry.

Spurgeon found a robust membership process indispensable to pastoral ministry.

As to the charge that church membership seems exclusive, Spurgeon might respond that this is kind of the point. As Chang summarizes, meaningful membership “makes the distinction between the church and world visible. . . . The church exists as a warning to the world and a comfort to God’s people that Christ knows those who are his” (110).

Nothing New

For many of our churches, as the COVID-19 pandemic waned and churches returned to “normal,” ecclesiology invariably rose to the surface. One of the more novel (or so it seemed) challenges facing churches was whether or not to live stream worship gatherings.

Spurgeon, it turns out, can help answer the question. A century and a half ago, he addressed those prone to stay home on Sundays rather than gather with Christ’s people:

There are some who even make a bad use of what ought to be a great blessing, namely, the printing press and the printed sermon, by staying at home to read a sermon because, they say, it is better than going out to hear one! Well, dear friend, [even] if I could not hear profitably, I would still make one of the assembly gathered together for the worship of God. It is a bad example for a professing Christian to absent himself from the assembly of the friends of Christ. (46)

Something unique happens, Spurgeon believed, when members of a church physically gather to worship as one body. A printed sermon—or indeed, a live-streamed one—is no substitute for the in-person assembly of God’s redeemed.

Timeless Approach

Spurgeon’s approach to church is timeless because it was rooted in biblical conviction, not convenience. “At the heart of his pastoral strategy,” Chang observes, “was the belief that the Bible is sufficient and speaks to how the church is to be led” (8). Though this book is written especially with pastors in mind, any Christian will benefit from letting Spurgeon shape his or her conceptions of church.

Spurgeon’s approach to church is timeless because it was based on biblical conviction, not convenience.

What might it look like if we reclaimed a confidence that God works in extraordinary ways through the very ordinary means he’s established? What if pastors concerned themselves primarily with carefully explaining and applying the Scriptures at every turn? What if church members took seriously their covenant commitment to one another rather than being content with casual attendance whenever their schedules happen to be free?

Not every faithful ministry will bring in thousands of worshipers like the Metropolitan Tabernacle experienced. But God’s blueprint for his church offers divine guidance for every congregation, large or small.