“You have seen the torches grow pale when men open the shutters and broad summer morning shines in?”

Good news is really good only when the original news is really bad.

I realized this again while recently re-reading C. S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces. I had read it 30 years ago in college and missed its depth. As a literature major, I kept fretting with the mechanics of the metaphor. I caught the intellectual point, but my heart was unmoved.

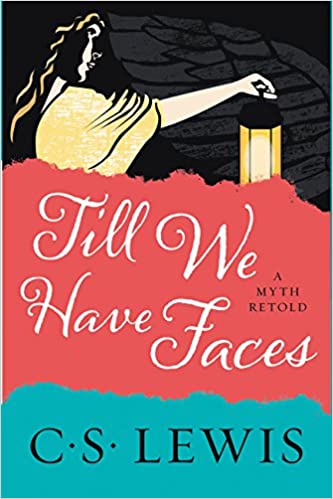

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold

C. S. Lewis

C. S. Lewis—the great British writer, scholar, lay theologian, broadcaster, Christian apologist, and bestselling author of Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, The Chronicles of Narnia, and many other beloved classics—brilliantly reimagines the story of Cupid and Psyche. Told from the viewpoint of Psyche’s sister, Orual, Till We Have Faces is a brilliant examination of envy, betrayal, loss, blame, grief, guilt, and conversion. In this, his final—and most mature and masterful—novel, Lewis reminds us of our own fallibility and the role of a higher power in our lives.

But several years ago, I picked it up again, this time reading it in one sitting on a plane flight. I had learned of a sudden and tragic event in a close friend’s life just a few days earlier. On this reading of Lewis’s novel, I was in no mood for academic exercises. I just wanted some authentic light in a dark moment.

On this reading of Lewis’s novel, I was in no mood for academic exercises. I just wanted some authentic light in a dark moment.

Till We Have Faces is the last novel Lewis wrote, published in 1956. It was written with the input of his wife, Joy Davidman, who later that year discovered she had bone cancer. She would be dead by 1960. Lewis would be dead by 1963.

Initially, it’s not a novel of youth, spring, or new things. It’s a novel of hindsight and old age—the wintertime of life. The narrator queen is like a pagan Solomon—a cynical monarch who has seen it all and, at the very last, finds redemption.

Brilliant—and Bitter—Narrator

Expressly, Till We Have Faces is a retelling of the ancient myth of Cupid and Psyche. However, the book is also the account of the life and reign of Psyche’s sister, Orual, who’s telling her own tale as the aged monarch of an ancient kingdom. She’s an insular and pragmatic personality, acerbic and capable in the world she rules.

Telling her strange story for posterity, this old queen presents a body of evidence, for her goal is to make a case against the divine. She details her complaints against the gods—their cruelty, hiddenness, jealousy, and trickery. But as she tells the story of hurt and injustice, something else develops. She realizes her case is, in reality, a case against herself.

Indignant, she discovers that, after all, she was the cruel and unjust one. Logical and learned, she discovers that, after all, she was the liar and deceiver. (The worst lies she tells are to herself.) Pragmatic and effective, a ruler who has built a solid and abiding empire, she discovers that, after all, her kingdom will be given to a distant relative she hardly knows.

Meanwhile, the one behind the stories was always drawing this queen to meet him, to show her that abiding satisfaction and truth never was found in the usual places—in shrines and magic, in book learning, or in politics. It was always, only, and forever found in him. Not found in a “what” or a “why,” but in a “whom.”

So the story she’s telling us about herself turns out to be a story about him. (After all, “He is at the back of all the stories,” according to another character in another Lewis novel.) As she reflects on the events of her life and her grappling with the gods, she has a new understanding of her life and those gods: “I knew that all of this had been a preparation. Some far greater matter was upon us. . . . ‘He is coming,’ they said. . . . The earth and stars and sun, all that was or will be, existed for His sake.”

And in a vigorously intrusive moment, he comes to her. The world tilts. The narrative flips. The hunter is now the hunted. And he enters in.

“You have seen the torches grow pale when men open the shutters and broad summer morning shines in?”

What About Us?

Tempted to a narrow focus on events—personal or public—which tell of a world broken by disease, violence, injustice, and checkered narratives, I often become like Orual. Vision replete with roiling chaos, I easily fixate on the “what” and the “why” instead of the everlasting Who.

Reading this novel in seat 15C with tears half-blinding my eyes and sniffling (as discreetly as possible next to my discomfited seatmate)—don’t worry, this was pre-pandemic—it was just the story I needed to re-focus. To remind me in a new way about this one who holds the world and even the life of my dear friend.

I often become like Orual. Vision replete with roiling chaos, I easily fixate on the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ instead of that everlasting Who.

He is far too concerned with loving us to let us idle along fixed on indolent accusations, or in the bland comforts of endless logical disputes, smoky mysticisms, or worldly pragmatics.

Less and More

So if the real story of this world is less about us and more about him, what kind of a story is it for, say, the modern American?

It’s that same story as for all lands and through all generations. It’s a most intimate love story of a groom for his bride, a father for his child, a king for his subject, a doctor for his patient, a farmer for his field. Communion with Christ is a most uncomfortable and invasive surgery, a nakedness, a subjection, a plowing and pruning, a knowing and being known.

We’re sick and sore, and he’s our surgeon—resetting bones, scouring infected places. We are weak and defenseless, and he’s our strong Tower and mighty King. We’re lost and calling out in dark places, and he is our finding, shepherding Father. In all this, he grows us into strong trees, flourishing on living waters.

We’re lost and calling out in dark places, and he is our finding, shepherding Father. In all this, he grows us into strong trees, flourishing on living waters.

We affirm his work and ours in the regular daily operations of men, and we don’t reject or despise the daily business of living, leading, and serving. And we believe in his covenant work across families and generations and through the church.

But indeed, there is an unavoidable, individual, personal meeting in which we must each face him unveiled. Like Orual, we may demand an account of him. But will find instead we must give an account for ourselves.