One of the most irreconcilable clashes in modern society is the conflict between Christianity and LGBT rights. At best, the two sides misunderstand each other. At worst, each fears that the ascendency of one means the zero-sum defeat of the other.

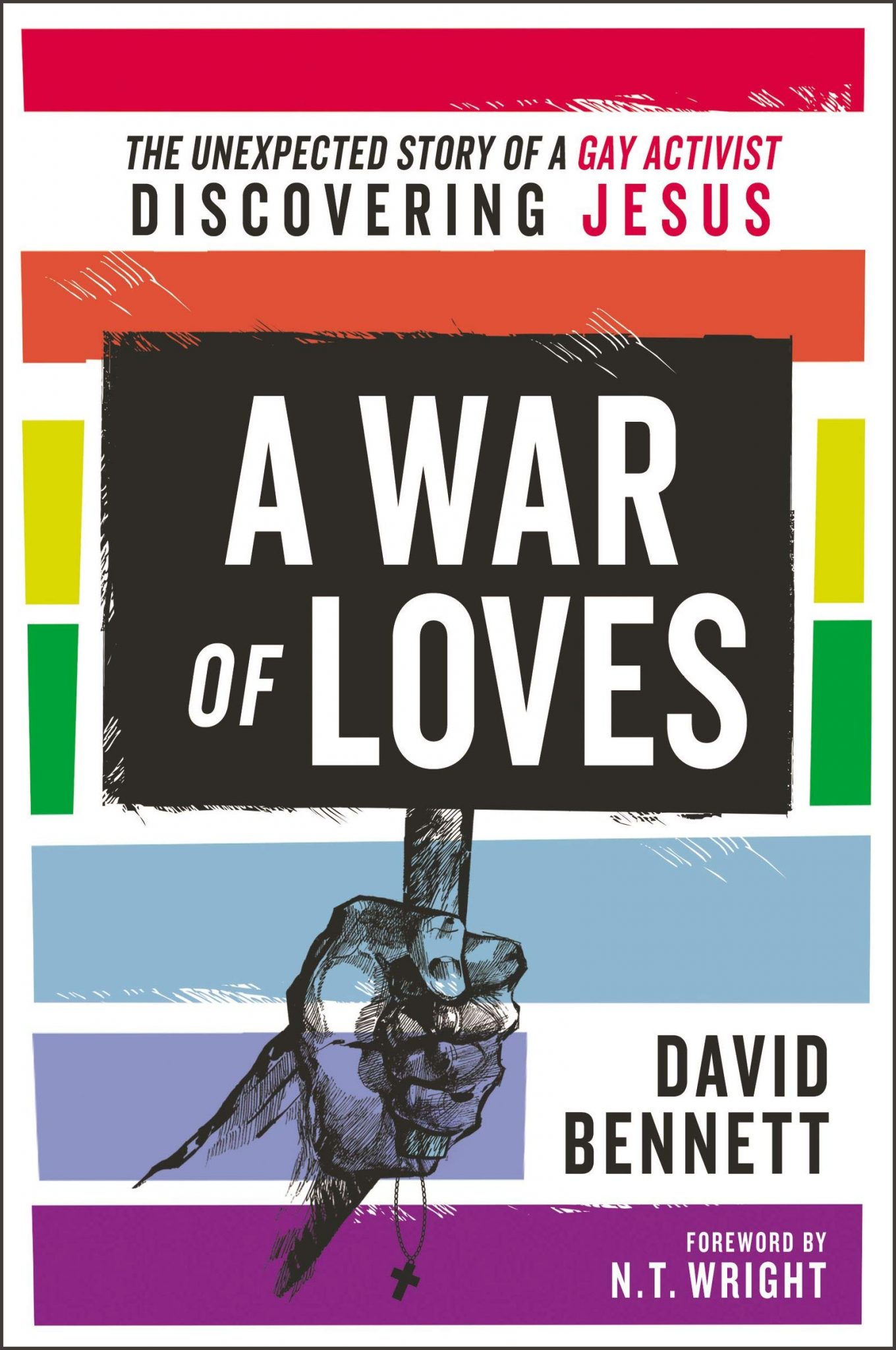

But in A War of Loves: The Unexpected Story of a Gay Activist Discovering Jesus by David Bennett, readers learn of an agnostic gay activist whose experiences left him searching for deeper meaning in life. He found it in the transformative love of Jesus Christ.

A War of Loves: The Unexpected Story of a Gay Activist Discovering Jesus

David Bennett

A War of Loves: The Unexpected Story of a Gay Activist Discovering Jesus

David Bennett

In A War of Loves, David Bennett describes his unexpected journey from gay activism and a distrust of religion to becoming a follower of Jesus, a journey that included pivotal relationships, supernatural encounters with God, and ultimately a new reconciliation between his faith and his sexuality.

At the beginning, Bennett declares his purpose in writing this memoir was “simply to share how God’s love has impacted my life.” Nevertheless, while these pages narrate a compelling testimony with incredibly insightful truths related to discipleship, friendship, and what true human flourishing looks like, they also contain some erroneous teaching about sexuality and anthropology.

Costly Narrative

A review like this one can’t possibly do justice to the personal details of Bennett’s work. You’ll have to read it for yourself to get the full treatment. Nevertheless, let me offer a few highlights.

The book is divided into five sections: The Search, The Encounter, Wrestling with God: Sense and Sexuality, The New Identity, and Reflections on Homosexuality and Christian Faithfulness. War of Loves contains substantive theological reflection on Scripture, community, celibacy, and friendship.

Bennett recounts his life as a child and adolescent aware of attraction for the same sex. As he tells it, he knew this attraction put him at odds with Christianity, and in turn he saw Christianity—and the Bible, “a dangerous book”—as the chief obstacle not only to self-fulfillment, but also to human rights.

But while admitting hatred for Christianity, the agnostic Bennett acknowledged that the intellectual trends of his early adulthood still left him feeling empty. From agnosticism to Wicca to Buddhism to existentialism to romantic relationships with other men, life’s purpose eluded him.

Through friendship with a Christian, Bennett came to faith. He recounts an almost-mystical experience with God’s grace at a pub, where he internally heard God ask, Do you want me? Bennett answered that he did, noting that he was exhausted by the “loveless world” around him. On recognizing that the Holy Spirit was working in him, he recounts his moment of conversion: “As I surrendered myself, something like hot fire coursed through my body. I knew I had become a Christian, and I began to weep.”

Bennett’s conversion wasn’t an immediate course-correction; he recounts his attempt to justify his desire for gay romance with his Christianity. Conversion didn’t make him a fan of the Bible, Bennett admits. The raw honesty of his awkward introduction to Christianity, while coming to grips with the cost of following Jesus, is a refreshing reminder of how jarring it can be to abandon the things that seems to make life worth living.

The remainder of the book is Bennett’s internal grappling with how to navigate life between two communities. The LGBT community had welcomed him and nurtured his desire for visibility, but he felt increasingly alienated because of his devotion to celibacy. The church, which he originally opposed, was now becoming an integral part of his life.

One of the most profound parts of the story is Bennett meeting old love interests and, at the prospect of indulging same-sex desire, concluding that acting on his same-sex attraction would be a betrayal of the love God had shown him. For a culture awash in an ethic that says every desire that comes from within should be acted on, Bennett’s story is one of costly discipleship.

Reflecting on what it means to forego gay relationships and sex, Bennett writes: “The very legitimate fear of giving our everything to Christ is the greatest enemy to discipleship.” Bennett is at his best when he writes about the cost of sacrifice and the promise of ultimate redemption.

Were more space available, I’d recount many more of the episodes vividly demonstrating the obedience that same-sex attracted Christians demonstrate in their celibacy.

Costly Obedience

I want to state the value of the War of Loves up front. David Bennett is a friendly acquaintance, and I appreciate his testimony and faithfulness to Jesus. He’s a brother in Christ. What’s more, Bennett has gone public with a costly narrative. It’s no easy task, in our polarized age, to tell of a gay activist’s conversion to Christianity—and become a Christian apologist at that. I’m grateful that Bennett’s story exists for others in similar situations. The church needs a multitude of stories showing that discipleship and biblical authority aren’t a self-imposed prison. Bennett’s narrative is a stunning foray into the freedom one can experience when captivated by God’s love in Christ.

The church needs a multitude of stories showing that discipleship and biblical authority aren’t a self-imposed prison.

Second, Bennett’s intellectual honesty shines through. At his conversion, he wanted to find a way to believe that gay relationships were reconcilable with Christianity. But he found the hermeneutical gymnastics of progressive Christianity unsatisfying. We should sincerely applaud Bennett for rejecting revisionist interpretations that supplant orthodoxy in the interest of self-justification.

Third, Bennett’s prose is a joy to read. He offers incredibly beautiful explanations on how fulfilled one can be when fully surrendered to Christ.

At the same time, there are significant problems with some of Bennett’s arguments, the kind that make it difficult to endorse the book without major qualifiers. Left unchallenged, my concern is that an otherwise helpful book could induce further confusion when the church needs clarity.

First, like the Revoice controversy that swelled last summer, Bennett attempts to retain some redeemable aspect to his experience with same-sex attraction. You might hear this called “celibate gay Christianity” or Side B Christianity. While I want to be respectful of Christian brothers and sisters who hold orthodox beliefs about the immorality of same-sex sex acts, it’s wholly problematic to hold on to any iota of an identity that Scripture considers sin. The notion of “identity” used in these debates is itself problematic language, since it is so subjectively defined.

We don’t attach other modifiers to our Christian faith when the modifier in question originates with sin or natures that are the product of the fall. We should no more endorse “gay Christianity” or “gay identity” than we should alcoholic Christianity, racist Christianity, or slanderous Christianity. We ought not modify our Christian walk with attributes born of fallen desires. When an individual comes to Christ—while their sin nature still awaits full redemption—they are dead to sin’s authority.

A Christian’s slavery to sin belongs to their past, not their present. The New Testament calls us to a Spirit-filled present and future. Throughout Bennett’s book, references to “identity” abound. To be fair, Bennett is right to conclude that his ultimate identity is found in Christ, but that doesn’t prohibit him from appealing to his sexual identity as the next most important thing about him. Elevating sexual orientation to the degree he does seems to make “identity” into an ethnos, which is why he expresses so much solidarity with the gay-rights movement.

Second, Bennett equivocates too heavily when it comes to Side A or Side B debates on the proper Christian response to homosexuality. These aren’t two sides of the same coin. Side A proponents—those who see no incompatibility with Christianity and same-sex sexual relations—have adopted a false teaching (and some a lifestyle) that is incompatible with Christianity. They’ve capitulated to the spirit of the age and have abandoned the authority of Scripture. Bennett seems to downplay these differences and characterize this disagreement as an in-house debate. Respectfully, it’s not. The New Testament is clear that unrepentant same-sex sexual behavior excludes persons from God’s kingdom (1 Cor. 6:9–11). Bennett downplays the seriousness of this division, accusing those willing to disfellowship over the matter as being factional or schismatic.

Third, Bennett is too sanguine about the broader gay-rights movement and gay subculture. This leads him to problematically claim there are elements of gay relationships that Christians should endorse. For example, he writes: “Gay unions and relationships, as many of mine did, can contain deep commitment, friendship, and sacrificial love that, when separated from sexual expression, I am sure, are important to God and are to be honored in these ways as forms of friendship.”

I agree that “deep commitment, friendship, and sacrificial love” are Christian virtues, but that doesn’t mean homosexuality is in some sense a virtue that enhances their legitimacy. Gay desire and behavior undermine “deep commitment, friendship, and sacrificial love” by placing them on a sexual spectrum. To treat these virtues as if they were aspects of homosexual orientation is to compromise them. Acknowledging the common grace that can come from any friendship needn’t require valorizing gay relationships or the gay-rights movement.

Conclusion

A War of Loves is at its best when recounting the gripping narrative of conversion and transformation. It contains a beautiful testimony of someone honestly wrestling with God’s love, Scripture’s authority, and Christ’s lordship.

For this, I am so deeply thankful for David Bennett and his story.

Nevertheless, the book falters at points by giving the reader an unbiblical view of human personhood—one defined by so-called gay Christianity. It also fails to see how profound the error of Side A Christianity is. To miss this is to soft-pedal a destructive error into which too many Christians today are falling.

In the end, I’m grateful for the testimony of this book. I just wish its teaching on other matters was more appropriately nuanced.