Taking the advice of C. S. Lewis, we want to help our readers “keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds,” which, as he argued, “can be done only by reading old books.” Continuing our Rediscovering Forgotten Classics series we want to survey some forgotten Christian classics that remain relevant and serve the church today.

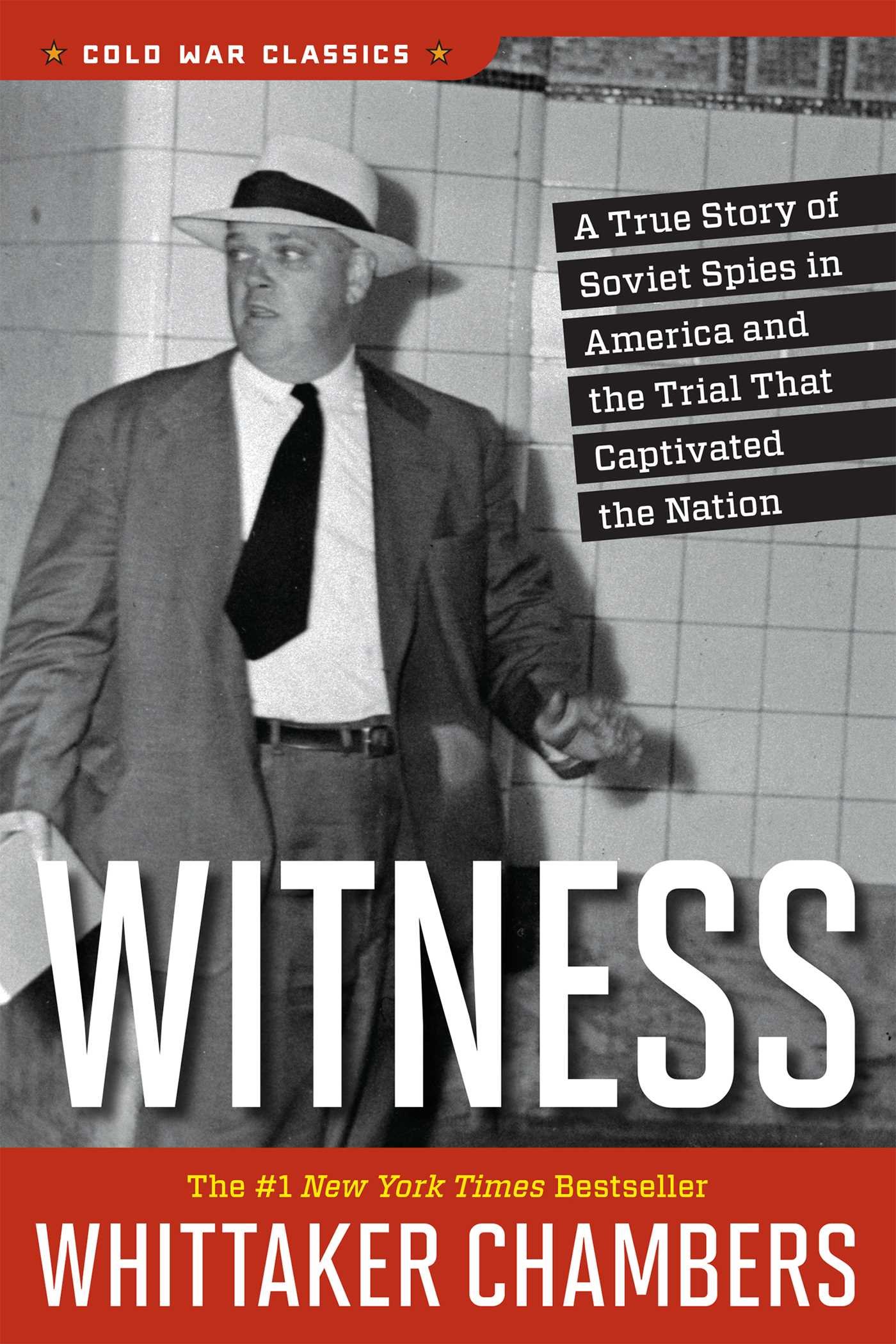

One of the biggest U.S. bestsellers of the 20th century, a Christian reflection on the modern world’s political and social crises, is almost unknown among Christians today. It was number one on The New York Times bestseller list for 13 consecutive weeks in 1952 because it is a powerful personal story of good, evil, despair, and redemption. The story is told with a literary beauty that can be compared without hyperbole to that of Augustine’s Confessions. But it is also worth recovering today because it would provide us with a fresh vantage point for thinking wisely about the problem of the gospel and modern politics.

In Witness, Whittaker Chambers used the lens of his amazing life story to show that the modern world has gone badly wrong because it has turned its back on God. He was diagnosing the crises of the 20th century, especially the confrontation between a smug, materialistic liberal democracy and the monstrous totalitarian systems of communism and fascism. But his diagnosis of how spiritual complacency creates political chaos provides just as much clarity about the crises of the early 21st century, like the breakdown of the moral consensus within liberal democracies into fragmented and polarized extremes on the Left and Right.

Spiritual complacency creates political chaos.

From global wars and genocide to the persistence of poverty in a world of plenty, Chambers described how the modern world has unleashed unprecedented political troubles. All these ills are the political expression of a decline in socially functional religion. In practice, if not always in theory, we believe that there is no rationality higher than the human mind and no morality higher than the human will.

Witness

Whittaker Chambers

For all its technical and economic marvels, the modern world does not provide people with the two things they really want most: something worth living for and something worth dying for.

Chambers’s Biography

Chambers’s life story mirrors the crisis of the modern world. He was a man with a passionate concern for justice, but he could see no viable answers for the political crises of the modern world. Driven to desperation, he became a true believer in communism. He eventually worked as a Soviet spy, participating in espionage, sabotage, and assassination. But this path produced an even more profound desperation, as it became clear to him that the communist answer—for which he had sacrificed not only his life but his conscience—was as bankrupt as all the others.

Then he turned to God in Christ. He left the communist underground, throwing away everything he had given his life to. Over the next 10 years, he became a political journalist and rose to the top of the profession as a senior editor at Time magazine. Then he threw it all away again, agreeing to testify to Congress about his work in the Soviet underground. Chambers’s heartbreaking testimony electrified the nation, but it cost him his career—as he had known it would.

The modern world does not provide people with the two things they really want most: something worth living for and something worth dying for.

Chambers wrote that his witness for God was a witness against the twin evils of the modern world. By throwing it all away and leaving the Soviet underground, he bore witness against the temptation of revolutionary violence. By throwing it all away again and leaving his career at Time, he bore witness against the temptation of materialistic success.

God or Man?

The fundamental question for individuals and for society, Chambers wrote, is: “God or man?” There have always been individuals who answered man. What is new in the modern world is that whole societies will now answer man, and organize their political lives around that answer. Some do this through the totalitarian politics of revolutionary violence, others through the liberal politics of materialistic success. The passing of the old, agrarian traditions of life under the pressure of modern technology and markets has left us without a reliable way to make religious faith an active and architectonic force in the structure of our lives.

Chambers’s profound radicalism lies in his unsparing, prophetic witness against the religious complacency of mid-century America. He identified this spiritual anemia as the root cause of our political problems. The communist East, he wrote, has chosen man, and practices totalitarianism because it has the courage of its convictions. The capitalist West has also chosen man, but it doesn’t want to admit this to itself. It is haunted by the specter of its Christian past, so it is not yet ready to abandon the rule of law and respect for human rights. But it has lost the spiritual conditions that make those legal structures humane and sustainable.

The rot in the political tree of liberal democracy is clearly visible and slowly spreading. The rot is there because the spiritual roots are already gone. Without God, Chambers warned, man can’t organize the world for man. Without God, man can only organize the world against man.

The rot in the political tree of liberal democracy is clearly visible and slowly spreading. The rot is there because the spiritual roots are already gone.

This was a breathtaking stand to take in 1952. America was still riding high on its victory over fascism. We were the global good guys, the saviors of the world. And the nominal Christianity of American culture, while it may have shown some signs of wear, still seemed basically immovable. To suggest that our political, social, and cultural order was spiritually bankrupt was like declaring that the sky was green.

Yet the testimony of this witness was heard. The book was a sensation. It topped bestseller lists, and quickly established a credible claim to be one of the most important books of the century.

Unfortunately, the success of Witness contained the seeds of its undoing. Fans on the political right, who relish the book’s devastating portrait of the evils of communism, have kept it in print. Yet, for just this reason, it gradually became misidentified as a mere right-wing, anti-communist tract. It is certainly anti-communist; it is one of the most important books ever written against communism. However, its attack on communism is grounded not in right-wingery, but in the holy love of God for a sinful humanity—a stance that set Chambers against the spiritual bankruptcy of capitalist America as well as the tyranny of the communist Soviet Union.

Lessons for Today

There is much we can learn from Witness for our own time. The idea that political dysfunction arises from spiritual dysfunction isn’t as radical among Christians today as it was for Chambers’s original audience. But Chambers provides deep understanding of the “hows” and “whys” of the connection between a nation’s spiritual state and its political state—vital knowledge if we want to outgrow the cheap and counterproductive responses to our dilemma.

Without God, man can’t organize the world for man. Without God, man can only organize the world against man.

Above all, I’m convinced that an encounter with Chambers would help Christians on the political left and right understand one another better. His witness against totalitarianism, with its staunch defense of the rule of law and human rights under a system of freedom and personal responsibility, would help Christians on the left understand conservative concerns better. His unsparing portrait of the many forms of injustice that thrive in America—the mistreatment of workers, the brutality of white supremacy, the alienation of the outsider—would help Christians on the right understand progressive concerns better.

Chambers broke with revolutionary radicalism and also with the pursuit of material success. There are vital lessons for all of us in both of those breaks.