Books that attempt to assess the legacies of several different thinkers aren’t new or, sometimes, particularly interesting. Far too often the thinkers are haphazardly selected, their thought then analyzed individual-by-individual without shedding new light or establishing meaningful ties among them.

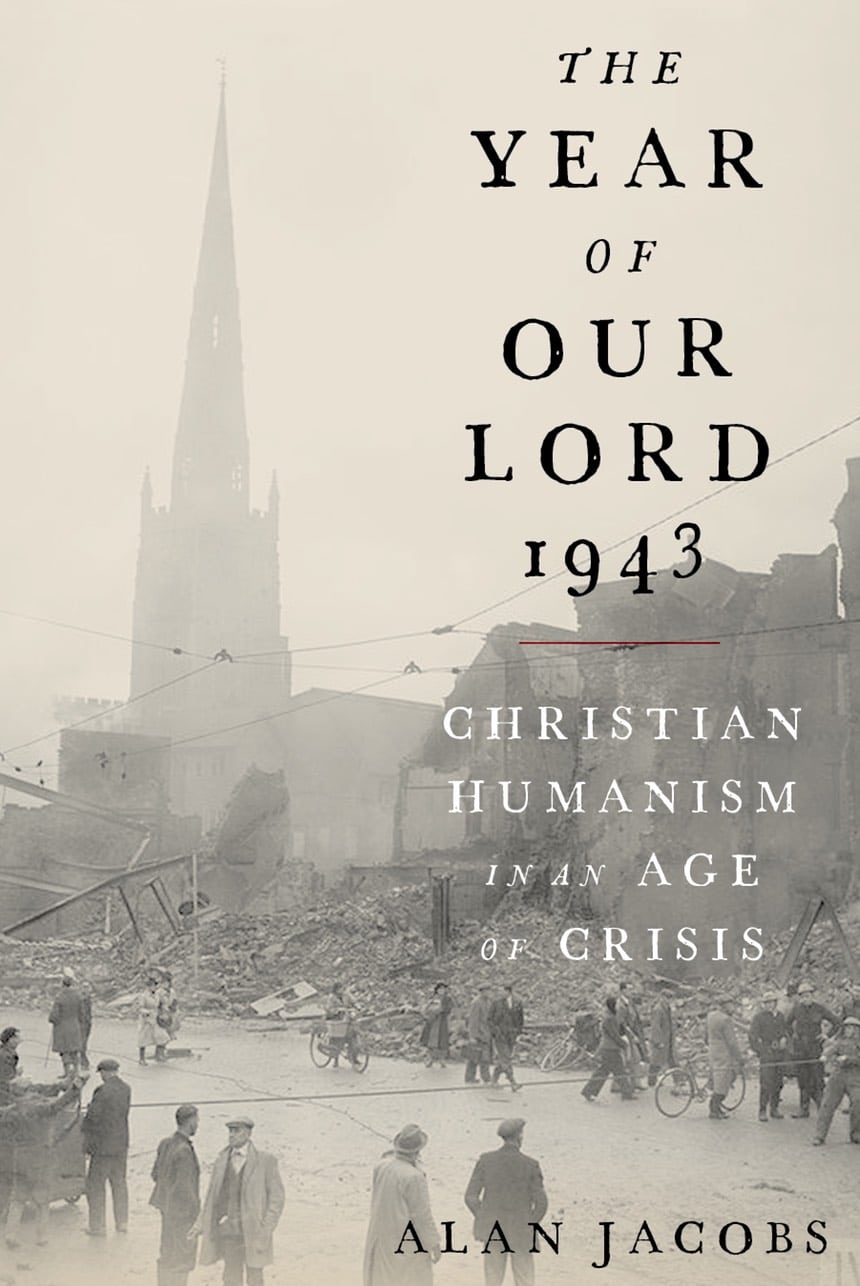

Thankfully, Alan Jacobs’s The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis isn’t such a book. Jacobs argues that in the final years of World War II, a group of disparate Christian intellectuals began thinking about what the shape of post-war Europe ought to be; and though they had few personal ties, they all came to broadly shared conclusions. The five thinkers Jacobs profiles are C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot, Jacques Maritain, Simone Weil, and W. H. Auden.

Jacobs, professor of humanities at Baylor University, calls their shared social vision “Christian humanism.” He develops it under the headings of humanist influence, the centrality of education, an openness to the possibility that contemporary events in the West had demonic influences, and the centrality of force to the regime the humanists were critiquing.

I don’t know Maritain, Weil, or Auden well enough to comment on how strong Jacobs’s handling of them is. But I do know Eliot and Lewis. And here I can say with great confidence that Jacobs’s work is a shimmering example of how scholarship can bless and illumine.

The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis

Alan Jacobs

The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis

Alan Jacobs

By early 1943, it had become increasingly clear that the Allies would win the Second World War. Around the same time, it also became increasingly clear to many Christian intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic that the soon-to-be-victorious nations were not culturally or morally prepared for their success. These Christian intellectuals—Jacques Maritain, T. S. Eliot, C. S. Lewis, W. H. Auden, and Simone Weil, among others—sought both to articulate a sober and reflective critique of their own culture and to outline a plan for the moral and spiritual regeneration of their countries in the post-war world. In this book, Alan Jacobs explores the poems, novels, essays, reviews, and lectures of these five central figures.

Eliot and Liberal Democracy

Eliot critiqued liberal democracy in multiple essays and poems, most notably in The Idea of a Christian Society, which argues that a liberal democratic system isn’t sustainable. Liberal democratic societies begin with the assumption that individuals have a right to define themselves independent of the claims of society, religion, politics, or any other unchosen body. Indeed, the main job of government is the protection and underwriting of individual self-expression.

Similarly, religion, the economy, technology, and a host of other social institutions are likewise understood as valuable only to the extent that they serve the self-actualization of individual people. On the other hand, to whatever extent government, religion, family, or neighborhood constrains individual self-identification, such bodies are considered unjust and dangerous. Eliot, writing in the 1930s and 1940s, already saw where such a regime would eventually arrive.

In The Idea of a Christian Society, Eliot writes:

That liberalism may be a tendency towards something very different from itself, is a possibility in its nature. For it is something which tends to release energy rather than accumulate it, to relax, rather than to fortify. It is a movement not so much defined by its end, as by its starting point; away from, rather than towards, something definite. Our point of departure is more real to us than our destination; and the destination is likely to present a very different picture when arrived at, from the vaguer image formed in imagination.

By destroying traditional social habits of the people, by dissolving their natural collective consciousness into individual constituents, by licensing the opinions of the most foolish, by substituting instruction for education, by encouraging cleverness rather than wisdom, the upstart rather than the qualified, by fostering a notion of getting on to which the alternative is a hopeless apathy, Liberalism can prepare the way for that which is its own negation: the artificial, mechanized or brutalized control which is a desperate remedy for its chaos.

In other words, liberal democracies run on a fuel they can’t produce themselves. A society with thick local community and a high regard for tradition is the sort that can explode into new forms of life under a liberal democratic order. Yet as the liberal democratic order becomes more entrenched, the very things that first gave it life will wither, at which point it’ll have to transform if it’s to endure. Here Jacobs’s treatment of force is particularly helpful, as the powers of science, bureaucracy, and the general ethos of technique (as understood by the French critic Jacques Ellul) would become ascendant as a means of propping up the decaying structures of liberalism.

Those familiar with Lewis’s work will recognize the ways it aligns with Eliot’s. Writing in The Abolition of Man, Lewis argued that the defining problem of Western society is that we deny the sources of virtue and wisdom while expecting folks to go on being virtuous and wise. “We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful,” is the particularly memorable image preferred by Lewis. Jacobs convincingly argues that Auden, Maritain, and Weil share this concern—the ascendant order at the end of WWII treated the heritage of Christian Europe with disdain but moved ahead on the assumption that the virtues produced by Christian Europe would endure.

Christian Hope

Jacobs’s book is perhaps most helpful in its acknowledgement of both the correctness of the humanists’ diagnosis and their view of Christian hope. Writing in The Lord of the Rings, Lewis’s friend J. R. R. Tolkien—who would share the same basic concerns as Jacobs’s five humanists—describes the hope of Frodo and the Fellowship of the Ring as a “fool’s hope.”

In the face of late modernity’s horrors, Christians are given several options for response. Jacobs describes the two most common. One is the route of the Christian pragmatist, symbolized (according to Jacobs) by Reinhold Niebuhr. This approach recognizes that a materialist liberal democratic society is ascendant and there’s no obvious way of overthrowing it; the Christian response, then, is to baptize the order as much as possible to save it from its own worst impulses.

We might, to continue with the Tolkien reference, call this the Boromir Option. The problem with this option is that the wisdom of late-modern man is inherently destructive, dedicated to the creation of machines and monsters that can destroy civilizations. To compromise with such “wisdom” is ultimately to trade the foolishness of God for the wisdom of man.

The second option is the “fool’s hope” symbolized so powerfully in the company sent to smuggle the Dark Lord Sauron’s Ring of Power into Mordor and destroy it. This is the hope of the Christian humanists. It’s foolish because it candidly acknowledges the likelihood of temporal failure. Tolkien called this “the long defeat,” and sometimes spoke of “fighting the long defeat together.” The Kentucky agrarian writer Wendell Berry, whose work also belongs to this school of Christian humanism, recently spoke with Bill Moyers about “being run over”:

MOYERS: What have you seen over a long life that prevents you from being fatally pessimistic?

BERRY: Well, hope. And . . . and in my work, in my . . . especially in the essays, I’ve always been trying to construct or lay out, map out the grounds of a legitimate, authentic hope. And if you can find one good example, then you’ve got the grounds for hope. If you can change yourself, if you can make certain requirements of yourself that you are then able to fulfill, you have a reason for hope.

MOYERS: Do you think that you’ve put yourself in front of the locomotive of history, waving your arms and shouting, “Stop!”?

BERRY: Oh sure. And you can do that very comfortably if you’re willing to be run over.

To the Hobbits

Jacobs concludes The Year of Our Lord 1943 by evaluating the ascent of personalism, a humane philosophy meant to treat people in their social contexts while avoiding the errors of both communism and romantic individualism. This personalism, Auden particularly saw, couldn’t ultimately defeat democratic liberalism on its own terms. “Ares has at last quit the field,” Auden would write at the close of the war, but this didn’t make him hopeful. It just meant the old strife between the children of Hermes and Apollo would resume. By the children of Apollo, Auden had in mind the technocrats, those who worship “the god of reason and order, manifested in our time through administrative bureaucracy, claiming the authority of ‘common-sense.’” Set against them, he held up the children of Hermes, those who “forego power and control to pursue the intricacies of reflection: they are, therefore, and necessarily, ‘we, the unpolitical.’”

Auden’s hope for the children of Hermes is striking—he knows the children of Apollo will win in the interim, but he allows himself to dream of a day when Hermes will again reign. And in the interim, he counsels those who resist Apollo with orders both amusing and memorable: “Thou shalt not do as the dean pleases. . . . Thou shalt not worship projects nor / Shalt thou or thine bow down before / Administration. . . . Thou shalt not be on friendly terms / with guys in advertising firms.”

The lines call three things to mind:

First, Berry’s own words in “The Joy of Sales Resistance,” where he gleefully tramples on the ad men of his day.

Second, consider the toast given by Tolkien at a dinner among readers of his books in Rotterdam in 1958:

I look East, West, North, South, and I do not see Sauron; but I see very many descendants of Saruman. And I think we Hobbits now have no magic weapons against them. And yet, dear gentle Hobbits, may I conclude by giving you this toast: To the Hobbits! And may they outlast all the wizards!

Third, I am reminded of the conclusion to C. S. Lewis’s underappreciated novel That Hideous Strength. The scientists and the bureaucrats have been defeated by an act of God, literally devoured by the animals they’d imprisoned for the sake of their cruel experiments. The two protagonists—the sundered couple Mark and Jane Studdock—are reunited in marriage, which is the great theme of the novel and Lewis’s rebuttal to the divorce age that now rules. As Jane approaches the house where she will find Mark, she sees his shirt hanging over a wall and smiles at the familiarity of it. She knows “it is high time that she went in.”

At the end of all things, the bride is reunited with her groom in a long-hoped-for reunion after an extended estrangement. Here we might give Eliot the final word, who wrote in his marvelous Four Quartets: “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”