Don Carson discusses the difficult question of why suffering exists from a Christian theological perspective. He explores biblical narratives and principles to provide a framework for understanding suffering, emphasizing its complexity and its relation to human sin, God’s judgement, and the ultimate hope of redemption. Carson seeks to offer not definitive answers but a means to think about suffering in a faithful, godly way, considering its role in the broader context of Christian faith and eschatology.

If you live long enough, you will suffer; all you have to do is live long enough. You may get through much of life relatively scot-free, but eventually the machinery wears out; you start losing your teeth or your hair or your mind or all three. If you live long enough, you’ll be bereaved. If you don’t live long enough, you’ll bereave somebody else.

Indeed, if you live long enough, you will be bereaved by losing your own children. A revered friend, now with the Lord, some years ago loss all three of his children. The first became a medical missionary to what was then the Belgian Congo. She was ganged raped during the Belgian Congo, came back home to recover, do some more medical training prior to going back out, tripped, fell down some stairs, and drowned in her own spittle.

The second’s death was almost as bizarre. The third died as an undergraduate at Cambridge of a brain tumor. Not once in all the years that I knew his dad and mum, not once, did I ever hear them whine. But if you live long enough, you will suffer. You’ll have friends die of AIDS. Or you’ll become aware of the suffering of others if you turn on the television and watch the effects of wars, floods in Pakistan, drought in the Sahel, and violence in many of our inner cities.

The result is if you don’t think about suffering seriously once in a while, then either you’ve lead a very sheltered life or it has been a problem for others until it comes existentially down to you. That’s the way many of us handle things; we don’t really think about them seriously until it does come to us, and then we’re forced into reflections that we might have had earlier.

Part of my hope this afternoon is not to provide the answer to suffering (I don’t think that Christians can do that) but to provide a kind of biblical frame of reference to enable us to think about these things in faithful and godly ways so that when suffering does come, as sooner or later it will, these biblical reflections serve as a kind of prophylactic medicine. They spare you in advance. When you are going through the deepest waters, if these things are not already in some measure in place, then the suffering is worse.

You’re not only suffering from whatever is making you suffer, you are also suffering because you have no frame of reference, even though you are a Christian, about how to think about these things in wise ways. It’s helpful to begin by remembering that the Bible itself reports many people who raised questions about suffering. It’s not as if it’s taken our generation to think these tough questions up. It’s not just Job (as we’ll see), but many of the psalms.

Or Habakkuk, for example, who can understand that God might use a nation to chasten another nation for its wickedness. What he cannot figure out is how God could use a more pagan and more violent nation to chasten his own covenant people, who however unfaithful they are, cannot be conceived as being more violent and more wicked and more pagan than the nation that is actually chastening them.

Or what shall we do with Job, whom the Bible portrays as magnificently holy, yet suffers and suffers and suffers under what can only be called the ages of innocent suffering? Or Jeremiah, the weeping prophet, who finds life so bitterly unfair that he curses the day he was born?

“Let the day that my mother bore me be blotted out. Let the sun hide. Let the man who brought my father the news saying, ‘A son is born to you—a son!’ Let him be cursed; let him die a thousand deaths. May my mother be perpetually pregnant with me never, ever coming out of the womb.”

This is pretty violent language for a believer, isn’t it? Imagine trying to create a three-point sermon out of that one! First, Jeremiah wishes his mother had been permanently pregnant. The rhetoric of the despair, of the disillusion, is formidable. Read it for yourself in Jeremiah 20.

Then there’s Elijah. “And I, even I only, am left.” Indeed, some who actually pass to the other side are portrayed in Revelation 6 as having a certain kind of empathy for those left behind, still crying, “How long, O Lord? How long?” So it’s not as if we are the first ones to think these questions up. The Bible itself forces us to think about these things if we’re reading imaginatively and thoroughly. Instead of telling you the answer, what I propose to do is to sink six shafts into biblical material which together support a kind of way of thinking about these things.

If you take any one of them and absolutize it, the answers come up to be a bit silly, they are reductionistic, but if you take these six shafts together and keep all of these pillars firmly in place in your mind, in your understanding of Holy Scripture, of God himself, then you are supporting a kind of structure that enables you to think about questions of suffering and evil in a framework that is not only faithful to Scripture but genuinely helpful.

1. Insights from the beginning of the Bible’s storyline

Without trying to go through the mechanics of things, nevertheless, the Bible insists that when God made everything, he made it good. At the origins of all that is bad, and thus the origins of all suffering, are bound up, finally, with human rebellion.

Now there are other things to be added. You take this rule absolutely, and it’s mistaken, but as a rule, the Bible is outraged at human sin and views human suffering as fundamentally deserved. Now I know there’s a place for innocent suffering; we’ll come to all of that, but nevertheless, that’s a frame of reference that is overwhelmingly stressed in many, many different parts of the Bible.

In other words, had there not been sin and rebellion, and with it the kinds of things we do to each other, the kinds of things we do to ourselves, the kind of offense we have offered to God so we attract his righteous judgement, there would be no suffering at all: no sin, no death, nothing of that sort.

At the risk of oversimplification, the Bible is not so much surprised that there is suffering and death as it is surprised that God doesn’t wipe us all out. In other words, what is marveled at in Scripture is the patience and forbearance of God, the goodness of God in actually calling out for himself a vast number of men and women from every tongue and tribe and people and nation who through no particular merit of the their own will stand around the throne on the last day and praise him for his grace.

That’s what the Bible finds noteworthy, remarkable, astonishing, both the Old Testament and the New Testament in this regard. Although there are individuals like Job and Habakkuk (as I’ve mentioned) who really find the problem of suffering really difficult, nevertheless, there is this jarring setup of the entire Bible’s storyline right at the beginning that is bound up with creation and fall. That’s a frame of reference for thinking about these things.

Now that’s not an incidental point. Do you see? Every system of thought … it’s not just Christianity … has to give some reflection or other to account for suffering and evil. There are some religious systems, for example, that think good and bad and suffering and pleasure and so on are all on the same sort of ordered scale, and we work through these things in successive cycles of life hoping to climb a little higher up in the scale, reincarnated again and again until we escape the scale that is drawing us down.

Still others have argued that all of suffering is bound up with material existence, and what we must ultimately have is an escape into spiritual nirvana, but our problem is fundamentally our physicality, not our rebellion.

And then there are a variety of systems based on natural philosophy; that is, the view in philosophical naturalism that all that is is matter, energy, space, and time; that’s all there is. There is nothing more, and all that happens is merely the result of atomic and subatomic particles banging against each other.

In this sort of frame of reference, you have to ask yourself, “Why should you be upset? Where’s good and bad in this? Why should you find it so odd that people suffer? Of course the laws of physics are prevailing here. Are you criticizing the laws of physics? There’s nothing to be outraged against. It’s just the way the molecules bounce!”

Now you may not find that very plausible, but all I’m saying is, “I don’t care what your frame of reference is, you have to think about suffering in any frame of reference or you are merely hiding your head in the sand. In other words, this is not a distinctively Christian problem; it’s a problem for anybody who thinks deeply at all, and every philosophy, every worldview, every frame of reference has to think about these things.

In that frame of reference, then, you must understand that the Bible sets the stage by saying at the bottom of it all is transgression, idolatry, the de-Godding of God, iniquity, fleeing from our Maker who is also our judge and our only hope, as we shall see, of redemption as well. That’s one of the pillars that anchors how we think about these things.

2. Insights from the end of the Bible’s storyline

In other words, unlike some frames of reference which picture life going round and round and round, and perhaps you become able to cycle up a little higher or regrettably you sink a little lower in the system; in fact, the Bible has a teleology; it has an endpoint. It is going somewhere.

It has come from somewhere, and it is going to somewhere, and where it is going ultimately is, on the one hand, a recreated universe with resurrection existence, a new heaven and a new earth, the home of righteousness, or perpetual and eternal judgement. In one sense, you will not be able to see nearly as much significance for suffering that goes on now in this in-between period between the beginning and the end, until you get to the end.

Now again, if you push that to the extreme, it is no answer at all, and yet, if you fit it in with the other pillars, it gives you a different way of looking at things. We sometimes sing this, do we not, in songs, choruses, hymns from the past, from the present? “It will be worth it all when we see Jesus.”

That’s what we sing. So we turn to the last two chapters of the Bible, and there the seer John hears the voice of God saying that there will be no more suffering or sorrow or tears or death, for the old order of things has passed away. And the entire church cries, “Yes. Even so, come, Lord Jesus.”

Now that does not explain all the suffering now. Do not misunderstand me, but on the other hand, even the suffering now looks a bit different when it is weighed against eternity. And indeed historically one of the great functions of the gospel itself in the church has been understood to be that which prepares us to die. Christians at many periods of the church’s history have been known as “those who know how to die well.”

My wife is a cancer survivor. Eleven years ago she had a double mastectomy, and just about everything that could go wrong did go wrong, and eventually we almost lost her twice. But partly because of this, she has become a bit of an angel of mercy to other people who have been through cancer of various sorts.

A few years ago in our church, there was a woman who had had breast cancer a few years earlier, and it was considered so early that she thought she had escaped with treatment pretty lightly. And then it came back. It was diagnosed in May, and it came back with a vengeance. It was vicious. By September, she was already quite ill.

Because this woman was well-known, not only in our church, but in the whole area for her activism and mission concern and leadership on many fronts, eventually our church held a one-day prayer meeting for her. There were 281 people who showed up from all over the area. I was out of town. My wife attended and many, many prayers were offered up for this woman, whom we’ll call Mary.

After all, Mary had not only run Bible studies and that sort of thing, she started a business using a whole lot of volunteers in large part so that the profits would all go to missions. She and her husband reserved half of their basement for things that missionaries need when they come home. They come home, and they don’t have blankets and toasters and electric kettles; they have to start all over again very often.

They provided these things, and she rounded them up secondhand, whatever. “No junk! Missionaries deserve better than junk.” She was a bit of a battleax in her own way, but she organized things magnificently, and all these supplies were there. She lead teams to help people in various corners of the world who needed help. She was a remarkable woman. So the church gathered to pray.

“O Lord, you know all the good that she has done. You know how her children, though they are young adults now themselves, they still need her, and her husband. Lord, you don’t want to cut off someone like this from all the good work she is doing. Isn’t Jesus the great physician, and yesterday and today and forever he doesn’t change? Will you not heal her? Lord, if two or three people on earth be agreed as touching anything, well, look at us … there are 281 of us, Lord!”

The arguments became stronger and stronger, the pleading more and more impassioned, until finally it was my wife’s turn to pray. She prayed, “Dear heavenly Father, if you would heal poor Mary, we would be so grateful. But if not, teach her to die well. Give her a hunger for eternity, a homesickness for heaven. Give her a heritage for her husband and children. Give her confidence in the Savior. Help her to see that this world is not our home. Help her to die well.”

Well, you could have cut the air with a knife. We were told afterwards that some of the relatives were rather hoping that my wife’s cancer would cast itself up in perfect vengeance so that she would experience a little more of what she was talking about. But you know what? That was the sort of praying that was done in the Puritan period all the time. All the time. It wasn’t even uncommon in most periods of the church.

It’s just nowadays with some much medical help, if somebody falls ill, we think the National Health Service jolly well better sort it out or I’ll sue! It’s another frame of reference, and it has trained us to think that our life, our being, our happiness, our frame of reference, our significance is all bound up first of all with this life, instead of seeing this life as in some sense a veil of testing and tears before consummated resurrection existence comes.

Listen … a church that is functioning faithfully to the gospel is self-consciously and repeatedly helping people to die well. Now that does not answer everything, but it’s part of the frame of reference that is intrinsic to the gospel. What it presupposes is that there is no utopia here. Many of us are perennial utopians. Utopia means literally “no place,” but we keep hoping there is a place.

If we just get the right result in the elections, if we just get the right political party, if we just have the right economic system, if we just have the right this or the right that, then we’ll have a perfect society. And of course, it never works out that way, precisely because although there may be better and worse policies, and better and worse systems, nevertheless, at the end of the day, you name the policy, you name the party, you name the system, and we can muck it up. It’s part of the entailment of the fall.

And after we have had all of our medicine, we’ll get hit by super viruses or more Alzheimer’s or AIDS will appear out of nowhere, for here we have no continuing city. And according to the apostle Paul in Romans 8, the whole creation groans in travail, waiting for the end for the adoption of sons.

I brought with me an essay by C.S. Lewis. It’s not exactly germane; it sort of hits this subject tangentially. It’s one I recommend you go online and download. You can find it in quite a lot of places. I have a paper copy of it from a book, Fern-Seed and Elephants and Other Essays on Christianity.

The essay is titled “Learning in War-Time.” Let me set it up for you. C.S. Lewis was an infantryman in World War I, that bloodiest and most stupid of wars where tens of thousands could be mowed down with machine guns from both sides, taken out with higher artillery shells in one barrage after another, one more rush through the trenches, and no advance except a few hundred yards and then a few hundred yards the other way.

In that war he saw most of his friends from his generation killed, but somehow he survived. A bare 20 years later, World War II broke out. The chaplain at the University Church in Oxford didn’t really know quite what to say, and since C.S. Lewis was already beginning to develop a name for himself as a Christian and was thinking about these things, he was asked to speak to the undergraduates.

How do you continue to study in war-time? Another world conflict where you mow down endless generations of people? How do you continue to study? Doesn’t all of life become ridiculous and insignificant, stupid, brutal? That’s all. So he climbed into the pulpit, and this is what he said (I’m not going to read the whole thing, just a few paragraphs):

“A University is a society for the pursuit of learning. As students, you will be expected to make yourselves, or to start making yourselves, in to what the Middle Ages called clerks: into philosophers, scientists, scholars, critics, or historians. And at first sight this seems to be an odd thing to do during a great war.

What is the use of beginning a task which we have so little chance of finishing? Or, even if we ourselves should happen not to be interrupted by death or military service, why should we—indeed how can we—continue to take an interest in these placid occupations when the lives of our friends and the liberties of Europe are in the balance? Is it not like fiddling while Rome burns?

Now it seems to me that we shall not be able to answer these questions until we have put them by the side of certain other questions which every Christian ought to have asked himself in peace-time. I spoke just now of fiddling while Rome burns. But to a Christian the true tragedy of Nero must be not that he fiddled while the city was on fire but that he fiddled on the brink of hell.

You must forgive me this crude monosyllable. I know that many wiser and better Christians than I do these days do not like to mention heaven and hell even in a pulpit. I know, too, that nearly all the references to this subject in the New Testament come from a single source. But then that source is Our Lord Himself.

People will tell you it is St. Paul, but that is untrue. These overwhelming doctrines are dominical [which means they come from Jesus]. They are not really removable from the teaching of Christ or of His Church.… The moment we mention these things we can see that every Christian who comes to a university must at all times face a question compared with which the questions raised by the war are relatively unimportant.

A Christian must ask himself how it is right, or even psychologically possible, for creatures who are at every moment advancing either to heaven or to hell, to spend any fraction of the little time allowed them in this world on such comparative trivialities as literature or art, mathematics or biology. If human culture can stand up to that, it can stand up to anything.”

And then he works out reasons why Christians should be able to think about microbiology or physics or whatever even while you are thinking about heaven and hell. Then he comes back to the war and (dare I say it?) trivializes war. It’s a moving piece, written not by some theorist, but somebody who has seen machine guns mow down generations.

Listen … this is the second frame of reference where we must draw some insights from Scripture. There are insights drawn from the end of time as well. We look at things very differently. In the Bible, earthquakes, tragedies, so-called natural desires are regularly treated as those things which portend final judgments. You think that these are terrible catastrophes now; in one sense, they are anticipations of the end.

Thus in Luke chapter 13, Jesus says, “What about natural disasters like the tower that fell on people, and a number of people died? Do you think this happened because they were more wicked than others?” Do you really think the tsunami that hit killed a lot of people because they were more wicked than others? “No,” Jesus says, “Unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.” In some senses, they are anticipations of the end.

3. Insights from the place of innocent suffering

For despite the large frame of reference, suffering finally gets traceable back to the fall. Despite these large things, there are quite a number of passages in the Bible that talk about innocent suffering. Although there is a way of looking at things that sees that if there had not been any fall, any curse, any death, there would be no suffering, yet many is the baby in arms who has not done something to deserve famine. And perhaps nowhere is this drama put more powerfully than in the story of Job.

Job, if you recall, is described as the most righteous man in the east, and as the poetry unfolds in this dramatic epic, which is the way it’s presented, the righteousness of the man is really stunning. He made a covenant with his eyes that he would not stare at a young woman in lust. No one in his area was permitted to be in starvation or poverty because he would look after them and provide jobs.

He prayed preemptively for his 10 children lest they should sin in their hearts and do something. He prays preemptively that God might spare them and save them. He is a remarkable man. What he does not know is what the readers of the epic know; there is a kind of background wager between God and the Devil himself.

The Devil is saying, “Job is your guy just because you’ve blessed him with so much. Take away the blessings and we’ll discover he’s not your guy at all, God. He’s just in it, just like a poodle in a house who knows which one feeds him and can be a nice little lapdog for the feeder.” So Job is God’s lapdog. “Take away the food, and we’ll see what sort of believer he is.”

So God sanctions the experiment. He begins by losing all of his cattle, his wealth, vast herds to marauding bands of Sabeans and Chaldeans. A storm eventually comes up, and the house in which his 10 children are having a party, (a party for goodness’ sake, an innocent party) it collapses, and all 10 children die.

As the story progresses, his health is taken away so that he is doing nothing but sitting in an ash heap picking at his scabs with broken pieces of pottery. In all of this, his wife, bitterly discouraged, adds a nagging voice, “Just curse God and die. Be finished with it! Damn the whole thing!” And he says, “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked will I return to death. The Lord gives and the Lord takes away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Then his three friends show up. With friends like that, who needs enemies? The only wise thing they do is sit down and keep quiet and weep with him and watch for the first week. Then their theological reasoning kicks in. “Job, do you believe that God is just?”

“Well, yes, I do believe that.”

“So God meets out punishments to those who deserve it?”

“Yes.”

“Has it struck you then, Job, that God may be trying to tell you something? Hmm?”

Job replies, at least initially a little mildly, he says, “Listen. I know that God is just. I know that no one can criticize his justice, but I have to tell you, I’m innocent. I don’t deserve this. I frankly wish I had never been born. This suffering is just beyond belief. I just wish I had never been born.”

And they affect a certain shocked arrogance. (I don’t know what else to call it.) “Job, do you hear what you’re saying? You’re saying you don’t deserve this, but doesn’t that mean God is doling out something that isn’t fair? Are you suggesting that God isn’t fair?” He then says, “No, no, I don’t want to say that. God is fair. God is holy. God is just. I can’t explain this, but I do know that what I’m suffering here is not just. This is not right.”

“Job, Job, you’re contradicting yourself. You’re on the edge of blaspheming God! If you say that you are suffering unfairly, and you believe that God is genuinely sovereign, then aren’t you really saying God is finally responsible for something unjust?”

The language gets ratcheted up and ratcheted up until Job says things on the one hand, like, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him!” On the other hand, “I wish I had a lawyer so I could sue the socks off him!” He’s saying both kinds of things. He’s right on the edge of anarchy, and yet at the same time he can’t let go of God.

Eventually there’s a fourth voice that kicks in, Elihu. We’ll skip him by. Eventually God speaks, and he offers two chapters of rhetorical questions. “Job, have you ever invented a snowflake? Were you around when I designed the hippopotamus? Have you ever cast a constellation into the ether? Have you ever designed Orion, for example? Can you give me an Orion?”

After two or three chapters like this, Job eventually says, “I’m sorry. I spoke too soon. I see. You’re making a right point. There are lots of things I don’t understand, and I should have remembered that.” God says, “Stand up on your feet; I’m not finished yet!” And he gives two more chapters of rhetorical questions.

Now at the end in chapter 42, God condemns the miserable comforters for their ridiculous, easy tit-for-tat theology: If you suffer, it’s because you’re bad; if you’re happy, it’s because you’re good. Life isn’t that simple. They have really been wicked in manipulating Job.

And Job is commended for saying basically the truth about God, but he is rebuked, nevertheless, because he thinks that God owes him an explanation. One of the lessons that Job must learn is that sometimes God is more interested in our trust than in our ability to provide a theodicy, an explanation of why these things happen.

There are quite a number of other passages we could push in this regard, but I’ll pass this aside. What we must see, however, is that God is more than the genie in Aladdin’s lamp. The genie in Aladdin’s lamp could give you whatever you wished, but at the end of the day, who controls the genie? The genie is controlled by whoever holds the lamp and rubs it.

The God of the Bible is not a God who is finally domesticated by us, provided we learn appropriately how to rub the Bible or whatever it is we do. Go to the right liturgy. Become a decent Anglican for goodness’ sake. Something to get God on side. God will not be domesticated. He is not just a supersized genie. There will be some mystery left over. He will not be domesticated.

4. Insights from the mystery of providence

Here is something where I could easily spend a couple of hours and not begin to scratch the surface, but it is one of those areas, again, where the Bible is full of this theme, and it is one that many of us as Christians today actually overlook. It’s one that needs to be brought back into the central place of our thinking.

Once again, the Puritans were better at this than we are. They wrote books with titles like, The Mystery of Providence. Let me put it this way. I want to argue that the Bible presupposes or explicitly teaches, two propositions simultaneously. Let me tell you what those two propositions are:

A) God is absolutely and utterly sovereign, but his sovereignty does not diminish or mitigate human responsibility.

B) Human beings are morally responsible creatures.

By that I mean, we choose, we believe, we disbelieve, we obey, we disobey, and there’s moral significance in what we’re doing. We are morally responsible creatures, but this fact does not vitiate or minimize God’s absolute sovereignty. Your head can hurt with those kinds of things. Let me give you two or three passages so you’ll see what I mean.

In Genesis 50:19–20, the old man has died, and Joseph, now in effect prime minister of Egypt, is confronted by his remaining brothers, who are worried that with the old man dead, Joseph may now wreak vengeance upon them for the fact that some decades earlier they had sold him into slavery.

So they give a song and dance routine (whether they’re telling the truth or not is not quite clear from the narrative) about how the old man had told them that Joseph was not supposed to do that and so forth. Joseph transparently is just a wee bit hurt by them thinking that he’s going to wreak havoc upon them. He says in effect, “Am I in the place of God? Listen, when you sold me into slavery, you intended it for evil, but God intended it for good, to save many people alive as it is this day.”

Because he went down into slavery, things worked out in God’s mysterious providence in such a way that the pharaoh had this dream interpreted such that when the seven good years came, he stocked up the barns and built bigger barns and prepared for the seven lean years which were coming, which helped not only prevent a great deal of starvation in Israel but actually helped to preserve the family itself of 40-odd people who were living up in Canaan who came down to Egypt to get food.

So, “When you sold me into slavery you intended it for evil, but God intended it for good.” Think carefully what the text does not say. It does not say, “God intended to send me down to Egypt in a chauffeur-driven air-conditioned limousine, but unfortunately you guys mucked it up, so I came down here as a slave instead. It’s not as if God had intended something good, and then God’s plans were somehow sideswiped and sidetracked and corrupted by these nasty brothers.

Nor does the text say, “You intended to harm me, but God, blessed be his name, came in on a white charger and turned it around. He’s a better chess player than you guys are. You can do all the nasty things in the world, but he takes the next move, and he wins in the end.” It doesn’t say that. It’s not as if the brothers are portrayed as having taken the initiative, and then God came and turned it all around. Or that God is portrayed as taking the initiative, and then the brothers mucked it up.

Rather, in one and the same event, you intended it for evil, but God intended it for good. Now how that works out in the mystery of providence I have no idea, but it is a very, very common theme in Scripture. If you want some more examples in Q&A later, I will provide them for you. Let me mention a couple of references you can read on your own.

Read, for example, Isaiah 10, verses 5 and following, where on the one hand, the empire of Assyria is seen as nothing but a tool in God’s hand, a battleax by which he chastens his people. Nothing more than a tool. And on the other hand, the Assyrians are responsible for what they do, and God will hold them responsible. Both are held to be true.

Perhaps nowhere is this clearer than in the cross itself. When the first whiff of persecution breaks out in Acts chapter 4, those who have been arrested go back and pray with the Christians who quote Psalm 2, “Why do the heathen rage and gather against the Lord and his Anointed …?” And after quoting Psalm 2, they go on to pray in Acts 4:27–28, “Indeed Pilate and Herod and the leaders of the Jews conspired against your holy servant Jesus.” That’s why Jesus went to the cross; there was a conspiracy, a corruption of justice.

And then the next verse, verse 28 says, “Indeed, they did what your hand had determined should be done.” If you take away either verse 27 or verse 28 so that you’re left only with the other one, you destroy Christianity. You destroy the whole Bible. Let me explain.

Supposing you believe only verse 27; you don’t believe verse 28. Jesus goes to the cross because of verse 27; that is, because there was a nasty conspiracy amongst the leaders and the rulers at the time (whether the Jews or the Romans or the Herodians … it doesn’t really matter.) There was a nasty conspiracy and that fundamentally is why Jesus went to the cross.

That means that Jesus went to the cross fundamentally as an accident of history, not to fulfill the great Passover theme, for example, of the Old Testament, or to make him out to be the great sacrifice of the ultimate Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur from the Old Testament, or because this was God’s plan from before the foundation of the earth, to send his Son to the cross, to pay for our sins in his own body on the tree. No, it was an accident of history.

How can you speak of the most significant thing at the heart of the Christian faith, the cross and resurrection of Jesus, as being nothing more than the result of a two-bit conspiracy in a minor Middle Eastern kingdom ruled from Rome? How can you see it that way? The cross suddenly makes no sense at all. It’s just an accident of history. Some people got crucified, and some didn’t.

If on the other hand you emphasize verse 28, you don’t have a place for verse 27. If you say at the end of the day, “The reason why Jesus died on the cross is because God had determined in advance that this was what would happen. So Pilate and Herod and the Jews, they simply do what God had determined in advance would be done. They’re not responsible. This isn’t a conspiracy; this is God’s sovereignty working out in a kind of fatalistic sort of way.

But you see, if there’s no evil in crucifying Jesus, if there is not conspiracy, if there is no sin because you appeal to God’s sovereignty, then if God is sovereign, there’s no sin anywhere. If from God’s sovereignty you learn that nobody is accountable for anything because God is sovereign, then there’s no sin to atone for; it’s merely a fatalistic universe. That’s all there is. There is no sin to pay for, so you don’t need a cross. Once again, you’ve destroyed the crucifixion. You’ve destroyed the significance of the gospel message.

But when you put the two together, however much the two verses hurt your head when you read them together, then everything is magnificently clear at the same time. On the one hand, Jesus does die because of a two-bit conspiracy in a minor country on the eastern end of the Mediterranean in the first century, and on the other hand, this is the magnificent plan of God in the mystery of providence to bring about a sacrifice who bears my sin in his own body on the tree.

To use the language of Revelation 13 and Revelation 17, “Indeed, this was bound up with God’s purposes from eternity past.” Christ in one sense is viewed as already having died in the mind of God before the world began, crucified for us, in God’s mind, before any time. “… crucified before the foundation of the world,” the text says.

But that means there is a running tension under the mystery of providence between God’s sovereignty which can be trusted, and evil and wickedness and conspiracy and ugly things that take place in this world. You have to factor both of them into your thinking all the time, all the time, so that you don’t want to say, “Ah, well, lots of people are dying in Pakistan; God is sovereign. Blessed be God.”

But you don’t want to say either, “This war that is going on in Afghanistan and just goes on and on and on, it’s just the result of the Devil and his works and human wickedness. God’s got nothing to do with it. God only does good things. He’s not responsible in any sense. He’s not overarching in his sovereignty over that war.” No, you still say that God’s purposes will prevail, and nothing escapes the outermost limits of his sovereignty.

To push a little farther, the Bible presents God’s sovereignty as being so sweeping that nothing escapes his outermost bounds. Yet, God stands behind good and evil asymmetrically; that is, he doesn’t stand behind the two of them the same way. He stands behind good in such a way that the good is always finally attributable to him, but he stands behind evil in such a way that the evil is always attributable to secondary causalities.

And if you say, “That just sounds a bit convenient for God,” I will say, “That’s the only God there is.” These themes are so common in Scripture. The Bible that insists that God is sovereign insists equally that God is unremittingly good. The Bible never presents God as sovereign in the sense that he stands behind good and evil exactly the same way. No, God is good. He is good, good. He is good, good, good. He is only good. To use the language of James 1: “He is not like natural light which always gives us shifting shadows.”

Here I am standing under a couple of floods, and one flood this way puts a shadow of the microphone down on the table here, and the light from over there puts it here. In the natural world, the light shines, and something gets in the way, and it automatically casts a shadow, but there is no downside to God. There is no shadow. With him, he never has a dark side.

In Star Wars, there is a dark side. The Force is sort of neutral; there’s an upside and there’s a downside. There’s a good side and a bad side, and which side wins depends entirely on you. But for God, he’s only good, good, good. There’s no downside; there’s no dark side. He is only good, and yet he remains sovereign over the whole mess, but asymmetrically so that he stands differently behind good and evil. One day we will see that it is so in the new heaven and new earth.

This is why we can trust him in the midst of our suffering. And that brings me to the fifth. On this one I wish I could spend a lot of time as well, but I cannot. I’ll barely state it; yet, it is fundamental.

5. Insights from the centrality of the incarnation and the cross

Do you see? When you cannot explain why you are going through the miserable pain that you are, what you can do if you’re a Christian, is return to Jesus writhing on the cross. For the God who is sovereign is also the God who sends Jesus to the cross.

I know a man who a number of years ago was with his wife and two children in another country. The daughter was about 14, almost 15, and while they were in this other country a long way from home, she heard that her best friend, who was also 14, had just been diagnosed with leukemia, just before, in fact, she was supposed to fly out and spend Christmas with this family who was overseas.

This daughter of this Christian family flew home to see the other friend instead and came back and was living with a family overseas. Lots of emails and phone calls back and forth, back and forth. But at the end of the day, in June of that year, the girl with leukemia died. The other one turned 15 that summer.

She wept well. She grieved well. She talked about it. She didn’t bury it, but it was still pretty devastating. This was her best friend. In September of that year, her father heard her crying in her room, tapped on the door, and said, “May I come in?” The girl was weeping buckets. The father put his arm around her and said, “Come on. Tell me about it.”

She burst into tears, and she said, “Daddy, God could have saved my best friend, and he didn’t, and I hate him,” and wept. The father said, “Well, I’m glad you told me. After all, God knows what you think. There’s no point pretending to think otherwise. You might as well be honest about it.

David doesn’t quite say that, but he comes pretty close to saying some pretty harsh things about God when things are going badly with him, too. You’re not entirely alone in this one. But before you become convinced that God has it in for you, that God is worthy of your hate, I just want you to think about two things.

First, do you really want a God who will do exactly what you want all the time, like the genie in Aladdin’s lamp? The Robin Williams version had just come out at that time. Laughing manically, the genie, but able to do anything. Great fun! But always under the control of whoever holds the lamp. Is that the kind of God you want?

Or is God big enough that sometimes he will do stuff that a 15-year-old doesn’t understand? That a 45-year-old doesn’t understand? More important, I want you to ask yourself this: Where in the Bible is God’s love most powerfully demonstrated? If it’s demonstrated at the cross, then what you must do again and again and again when you don’t understand is return to the cross. Not simply because that’s where you find forgiveness of sins, but because that’s where you find the most unqualified display of God’s love. God did not have to send his Son.

You lost your best friend; God lost his Son. In fact he didn’t lose him, he gave him, not in an accident, but in a divine plan so we might be forgiven and renewed and become sons of God ourselves. And when everything else falls away, that is where you must anchor your faith. I believe in the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ who suffered and died and rose again. I believe in that God, that kind of God. Do you see? I know this family well. That girl was my daughter.

6. Insights from taking up our cross and following Jesus.

And thus, for example, from the persecuted global church worldwide. For the fact of the matter is much of the suffering we talk about that concerns us has to do with economic difficulty because of the downturn in the economy. It has to do with cancer. It has to do with the infirmities of old age. Getting old is not for wimps. It has to do with divorce. It has to do with bereavement.

All of those things, of course, were faced in the first century as well when the New Testament was written. Yet most of the suffering that is talked about in the New Testament is not about those kinds of things. Most of the suffering that is talked about in the New Testament, which does reserve some allusions for illness and death and bereavement (yes it does talk about some of those things), but most of it is actually about persecution.

Thus, for example, Philippians 1:29, “For it has been granted to you on behalf of Christ not only to believe on his name, but also to suffer for his sake.” Do you hear that? It’s been granted to you. This is your blessed privilege. It’s been granted to you as a gift, not only to believe, (yes, yes, yes, that’s good. I’m glad I’ve been granted faith), but also to suffer for his sake.

When Jesus in Matthew 16 in Caesarea Philippi starts to talk about his own impending death, and Peter is having difficulty absorbing it, what Jesus goes on to immediately say is, “And you know what? If you’re my disciples, you will take up your cross and follow me.” Now today when we speak of “taking up a cross,” or “we all have our crosses to bear,” we are talking about some relatively minor irritation. “I’ve got an ingrown toenail.”

“Well, we all have our crosses to bear.”

“You should meet my mother-in-law.”

“We all have our crosses to bear.”

That’s the way we think, do you see? But in the first century, nobody talked about the cross like that. Taking up your cross in the ancient world was a hideous thing. There were actually moral instruction pamphlets written in the ancient world about not joking about the cross, about crucifixion. You could no more joke about the crucifixion in the first century than you can joke about Auschwitz today. It’s just not done.

So when you picked up your cross, it’s because you had already been condemned to crucifixion, and you were picking up the cross member and heading out to the place where they would tie you or nail you to that cross member and hoist it up on the upright. And there you would die, stripped naked and panting for breath until, finally, you died of shock or asphyxiation or loss of blood or weakness. You died.

And Jesus says, “If you’re going to be my disciple, you have to take up your cross and follow me.” In fact, in one place he says, “You have to take up your cross daily.” For bound up with following Jesus is dying in a sense to self-interest, and the only adequate parallel that Jesus can think of is crucifixion. Most of us in this room will not have to suffer physically for our faith.

But a few months ago I was in the Middle East, and I met quite a few Christians who have suffered quite a lot for their faith: in jail, beatings, torture, full of the joy of the Lord, counting it a privilege. Isn’t that what the Bible says? “It’s been granted to you on behalf of Christ not only to believe on his name, but also to suffer for his sake.”

Isn’t Acts 5:41 a remarkable passage? The first time the apostles are beaten up, we read, “Then they rejoiced that they were counted worthy to suffer for the Name.” Do you know what was going through their heads? I know what was going through their heads. After all, just a few weeks earlier in the Farewell Discourse, Jesus had explained to them at some length how there would be suffering and there would be persecution and a slave is not above his master.

“If they persecuted me, they will persecute you.” That’s what Jesus had said on the night he was betrayed. He had taught them all of these things. And since then, Jesus had died, risen again, the Holy Spirit had fallen, there had been Pentecost, sermons, thousands of people converted. Things are going swimmingly.

Then, 5,000 people. Christians everywhere. Bible studies from house to house, and where’s the persecution? The last thing Jesus talked about before he went to the cross himself was that there would be persecution, and to enter into Christ and his glory would be to follow Christ and, in some measure, take up his cross themselves. And all they are seeing is revival and reformation and no persecution.

Then the first wave of persecution comes, and the apostles say, “Thank you, Jesus.” They rejoice that they’re counted worthy to suffer for the name. It’s finally come as the master said. “Thank you that I can follow the master in this respect, too.” Doesn’t that change your perspective?

If we suffer with him, we will reign with him. I have to tell you, as I talk to Christians in the Two-Thirds World where persecution does break out, although some of them are under enormous stress, and some of them are in fear and all the rest, none of them romanticize about it. Yet there is a kind of stable faith and joy in the Lord that is grounded in eternity and in the privilege of following Christ. Let me conclude.

What I have not tried to do here is provide a kind of proof-texting approach that gives you six verses to memorize, and you’ve sorted out the problem of evil. What I’m trying to show is the Bible gives us ways of thinking about these things that are grounded in great truths, that are grounded in great pillars of the faith, that are part of the way Christians must think.

When these pillars are locked together, they affect one’s stance so that you get passages like 2 Corinthians 4, “Outwardly this old man is wasting away, but inwardly we’re being renewed and strengthened day to day.” My wife put that on the fridge door in big letters when she wasn’t sure she was going to survive from cancer.

The second thing I must say is this talk has focused on intellectual and worldview issues; that is, the way we are to think about these things, because that was what I was asked to do. But I would be the first to insist that when people are going through an actual crisis, something rather different may be needed.

Sometimes people are so blind to hurts that they don’t need intellectual arguments. In some kinds of crisis what they need is helicopters to bring in fresh water, people on the ground to administer medicine. Sometimes what people need when they’re grieving over a loved one is someone to put an arm around them and take the kids out for a walk and clean the house and fresh meals. Sometimes they need counseling and a listening ear until a little more time is past. Sometimes what they need in a crisis is a police force to stop the looters.

Do you see? I’m not denying any of those realities as well. This is not merely an intellectual problem. Yet, I still insist that thinking about these things, getting these pillars straight in our mind, is prophylactic; it is stability grounding.

Finally, Christians who get to know God well do not, as a rule, think in terms of theodicy, that is trying to justify the ways of God to men. By and large, that’s not what they do. Rather, they think in two other categories; that is, they tend to think about what is really needed is reformation or revival. Let me give you an example.

In Nehemiah chapters 8 and 9 when the people have come back from the exile and they’re facing difficulties and challenges, they’ve finally got this wall up, and they review their own history. Instead of making excuses, “God, why did you do this? Why did our fathers get sent away? Why was there so much suffering? Why is there no king in David’s line on the throne?”

That’s not what they do. What they do is they pray, “Lord, we look over our history, and we see how much sin and wickedness and unbelief and self-focus and raw idolatry there is. We beg of you, please, have mercy upon us and send reformation. Send your Spirit. Transform us, and give us genuine revival.” Let me tell you, when people know God well, that’s the way they pray, rather than in terms of bitterness. And finally, when people know God well, likewise, they regularly speak of the goodness of God in these matters.

One last story, and I’m done. I teach at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School near Chicago. A number of years ago there was a missionary sent out to Bolivia; we’ll call him, George. He went out to Bolivia, learned the language well. He was a tall, thin man, single, 6 feet 4 inches, but he was a very effective missionary. He learned the language and the culture well and fit right in and was a good Bible teacher.

He became so prominent in Bolivia that eventually the mission that he served sent him back to Trinity to do a PhD so that he could go back to Bolivia and help in theological training. Before he came, in fact, he met a single missionary down there, and the two of them got married and had a little girl. So when they came to Trinity, they were in their late 30s, and they had a little girl who was 3.

George started his PhD studies preparatory to going back to Bolivia. In the first six months of his studies at Trinity, his wife was diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer. To make a long story short, she survived it, he dropped out of his studies for a while, she seemed to be coming out the other side, he went back to his studies for another year, and he was diagnosed with advanced stomach cancer.

None of the hospitals in the Chicago area would do anything for him. He was considered a terminal case, except medicine to keep him going under hospice care. The mission decided to send him up to Mayo Clinic, and they were willing to give him some experimental medicine that was really used for colon cancer. They took out 90% of his stomach, started him on this rigorous treatment. He was already thin; now he became skinny as a rake.

Now he had to eat every two or three hours, little bits of food because his stomach couldn’t store anything. He’d wake up in the middle of the night and have a little snack and go back to sleep. But he came out of the end of it, came back to work on his PhD. And then his wife’s cancer returned, and she died.

In all of this, Christians at Trinity and their family in the church helped him and his daughter. The last I saw him he was back in our church because he had finished his PhD, his daughter was 9, almost 10 now, and they were heading back to Bolivia. For half an hour he preached in our church, and he talked incessantly about the goodness of God. I want to tell you, that’s not extraordinary. That is simply normal Christianity. That’s all it is. Let us pray.

Grant us such a hunger and thirst for your Word and through your Word to know you, our Maker, our Sovereign, our compassionate, tender Father, the author and finisher of our faith, the one who has sent the Lord Jesus to be our Savior and Redeemer, our Judge, the one who brings in the new heaven and the new earth, that we will so know you that we will be able to say with Job in the harshest of times, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him,” and find in Christ Jesus such goodness, such unimaginable love in the midst of suffering, such comfort in the midst of loneliness, such love that we will be full of testimony to the grace of God in our lives. For Jesus’ sake, amen.

Female: Hi. Just a quick question. Well, a huge question, really. On a global scale, one of the things that has puzzled me a lot is why some of us are privileged enough to be born say in Australia or in America or in a first-world country? Sure, we may have suffering of various degrees along the way.

What about the people born in what we might consider hopeless conditions where we know they’re going to die or have a high chance of dying? Their families may or may not know about God; therefore, they may or may not have the opportunity to have that reassurance or other factors that can assist them. I just wondered, as briefly as you can, just to help with a bit of an idea about that. Thank you.

Don Carson: What I would say is really an application of the kinds of pillar things I have already sunk. In other words, I’m not going to say anything new. Let me just tell you how it works out, how thinking about those pillars works out in these kinds of cases as well.

First, they’re under the mystery of God’s providence. So often, even in the worst cases of suffering, there are also deep instances of corrupt governments, heritages of despotism, the kind of tribalism that is bloody. What we sometimes forget in much of the Western world is there was a history of not only the Enlightenment, but counter to the Enlightenment, a kind of working out of an awful lot of Christian faith that emphasized honesty and integrity in dealings and hard work.

People joke about the Puritan work ethic, but many of us are afflicted with it. It’s a residue of things that is evaporating now in the culture. But some of the things that are blessings in our culture have come about because of the transformation of the grace of God in Christian witness and convention and heritage in the past.

Now, I’m certainly not trying to say that everything that’s good in Western culture is a result of the Christian faith; that’s not the case. But there is more than a little of that. I am told that in one very dominant east Asian country one of the things that they have been trying to analyze about the Western world is how Christianity has made more workers people of integrity, and they want to know how to transport that into their country. Well, I could tell them, “Let us go and do some evangelism with a full-orbed biblical frame of reference.” So there are things along those lines as well.

Second, under the first one, what is perhaps more surprising than the fact there is a lot of suffering in the world due to inequity is that the grace of God has been as good as it is in allowing so many people to suffer less. Again, you see, that’s coming out of a different frame of reference. What’s surprising is God’s forbearance.

Third, you need to look on a longer time scale. After all, 150 years ago we were all dying at the age of 47 as well. You must realize that these things we now take for granted in the West are relatively recent developments when you look over the course of the last two millennia, for example.

Meanwhile, this Western world that’s so hyped up that we’re so contented with and we’re grateful for, don’t forget it’s the Western world that produced two massive world wars. We’ve just come through the bloodiest century in human history. You have to remember that the worst violence in that century actually came out of not Africa, but Europe.

There are more things to think about in these sorts of frames of reference than just the latest picture on our TV tube of somebody with a leg blown off in Afghanistan. There are frames of reference that don’t explain it all away, but that put it under a bigger rubric than compassion devoid of trying to think things through in a broader theological grid.

Male: I, along with many others, I’m sure, found this very helpful. I was wondering, say, some of those things to non-Christians who are suffering deeply.

Don: I have given talks like this adapted for non-Christians in evangelistic contexts, evangelistic series. I think it can be done because it is the truth. Now, what I would say both to Christians and non-Christians who are suffering deeply is that sometimes they are not then ready to hear anything. That includes Christians as well as non-Christians.

You can be so sunk in the mire that what you really need is an arm around your shoulder and somebody to help you out of it and somebody to listen and help you paint the house and whatever has to be done. So that I tried to indicate that even in a couple of asides tonight by saying, “It’s not at the end of the day merely an intellectual sort of argument, and if you’re in a position where you’re crying so much inside that you cannot hear, what can I do to help?”

Yet at the same time, there is sometimes in the non-Christian world a kind of arrogance bound up with the question, “Oh, if God is like that, why should he care? Why should we respect him at all? Why should we give him any ear when there are children dying of famine in Ethiopia?” And sometimes I want to say, “If this is resolved for you, and you just want to argue, I’ve got nothing to say to you. If you want a serious answer to a serious question, then listen up. Give me an hour. Understand the frame of reference, and tell me that you can walk away from Jesus and not feel anything.”

So I don’t duck this one when I’m doing evangelism, but it’s the sort of thing where a one-shot answer, a one-line answer, is not going to go very far. It’s a frame of reference. It’s a way of looking at all of reality. I wrote a book a number of years ago called How Long, O Lord: Reflections on Suffering and Evil that tries to tease this out at greater length.

The aim, again, is to establish a frame of reference that makes sense, even if it doesn’t explain everything away. So occasionally if you’re dealing with a really hard-headed undergraduate, “How can you believe all that rubbish about God when there’s all this war and suffering going on?” Then my answer will be, I confess (in private, not in public), “Why should you give a rip? They’re just bouncing molecules in any case. Why are you so upset?”

Because I want him in that case to see that he’s got as many problems as me. The fact that he is upset is already presupposing that he thinks there should be a moral order. If he’s so convinced with his atheism, why is he even upset? Do you see? So sometimes you have to turn the tables just a wee bit, too. You don’t want to sound like a smart-aleck in public, but one-on-one you have to push back sometimes.

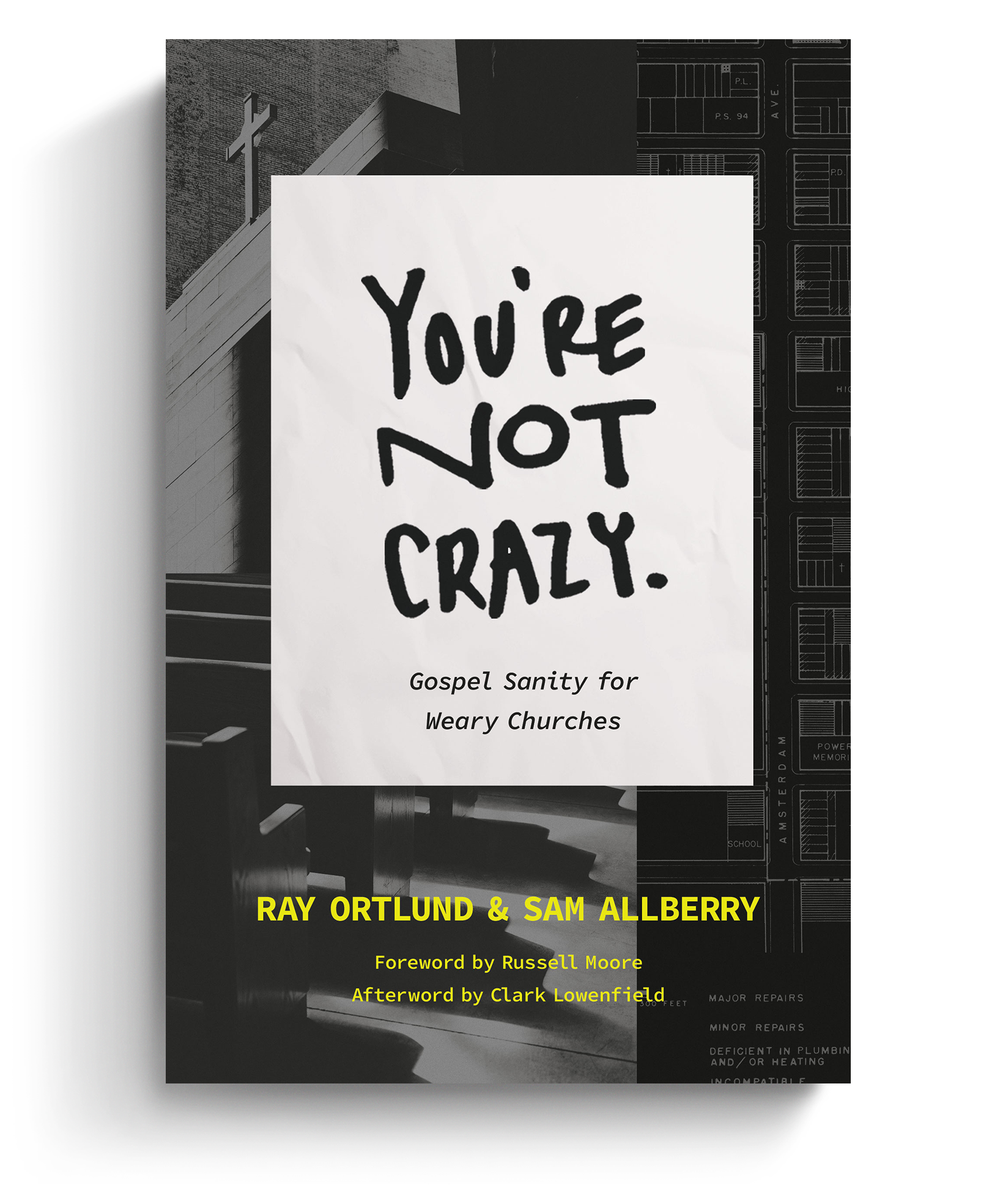

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.