Volume 45 - Issue 1

Politics, Conscience, and the Church: Why Christians Passionately Disagree with One Another over Politics, Why They Must Agree to Disagree over Jagged-Line Political Issues, and How

By Jonathan Leeman and Andrew David NaselliAbstract

Today many evangelical churches feel political tension. We recommend a way forward by answering three questions: (1) Why do Christians passionately disagree with one another over politics? We give two reasons: (a) Christians passionately care about justice and believe that their political convictions promote justice, and (b) Christians have different degrees of wisdom for making political judgments and tend to believe that they have more wisdom than those who differ. (2) Why must Christians agree to disagree over jagged-line political issues? After explaining straight-line vs. jagged-line political issues, we give two reasons: (a) Christians must respect fellow Christians who have differently calibrated consciences on jagged-line issues, and (b) insisting that Christians agree on jagged-line issues misrepresents Christ to non-Christians. (3) How must Christians who disagree over jagged-line political issues agree to disagree? We explain three ways: (a) acknowledge leeway on jagged-line political issues; (b) unite to accomplish the mission Christ gave the church; and (c) prioritize loving others over convincing them that your convictions about jagged-line political issues are right.

John Piper, who pastored Bethlehem Baptist Church for over thirty years, talks about two groups within the church who feel tension with one another.1 One group is passionate about evangelism and global missions, while the other is passionate about social action such as ministries to the poor, recovering addicts, women with crisis pregnancies, or marginalized minorities. Piper loves both groups. He has tried to breathe oxygen on their fires. And he has attempted to bring them together by reminding them that Christians should care about relieving suffering—all of it—especially eternal suffering.2

Today many evangelical churches in America feel a similar tension in approaching politics.3 All Christians care about justice, but they differ—sometimes passionately—about how to identify injustice and how to right those wrongs. Some churches even feel they are at an impasse over such issues and that the result is quiet fractures.

We don’t want to overly complicate that political tension, nor do we want to cover it with a band-aid. We recommend a way forward in this article by answering three questions: (1) Why do Christians passionately disagree with one another over politics? (2) Why must Christians agree to disagree over jagged-line political issues? (3) How must Christians who disagree over jagged-line political issues agree to disagree?

We have our own opinions on politics, but our goal in this article is not to convince you that our political judgments are right on issues such as immigration, tax policy, healthcare, welfare, global warming, gun control, or free speech. Nor is our goal to persuade you to vote for a particular political party. Our goal is to help Christians understand why, when, and how they must agree to disagree in political matters. Politics has a reputation for being divisive, dirty, disagreeable. Yet Christians (of all people!) should be able to both hold firm opinions about politics and discuss politics with one another generously—in a way that is kind, considerate, friendly, pleasant, humble, and respectful. Basically, in a way that prioritizes loving others.

1. Why Do Christians Passionately Disagree with One Another over Politics?

Sometimes fellow church members mildly disagree over politics. For example, one American votes for a Republican candidate, and another votes for an independent candidate. But our focus here is on passionate disagreements, ones that negatively affect how church members think about and relate to one another—that affect their ability to prioritize love. They may feel skeptical or even angry toward one another: “How can she be a Christian and support that?!” Christians passionately disagree with one another over politics for at least two reasons.

1.1. Because Christians Passionately Care about Justice and Believe That Their Political Convictions Promote Justice

Let’s break this first reason down into five components:

1. Justice according to the Bible is making righteous judgments. That is, justice is doing what is right according to the standard of God’s will and character as he has revealed it in his word. The word justice first occurs in the Bible when God says that he chose Abraham and his descendants to bless the nations “by doing righteousness and justice” (Gen 18:19).4 A third of the 125 times the word justice appears in the OT, the word righteousness is next to it (44 times). The standard of justice is not “contemporary community standards”; it is God’s righteousness. Justice and righteousness begin with God’s own character. What God commands humans to do expresses his will and character. God’s righteousness is what makes human rights right. What humans call rights are right only if God says they are right.

The word justice in the Bible is interchangeable with judgment. It’s the noun form of the verb judge. Justice is fundamentally the activity of judging or making a judgment. So we can define justice according to the Bible as making a judgment according to God’s righteousness. Or more simply, making righteous judgments. This definition has two components: a standard (God’s will and nature as Scripture reveals) and an action (applying the standard or making a judgment on the basis of that standard—i.e., doing justice).

King Solomon illustrates what it looks like to wisely make a righteous judgment. After Solomon discerned which prostitute was telling the truth about her baby, all Israel “stood in awe of the king, because they perceived that the wisdom of God was in him to do justice” (1 Kgs 3:28)—that is, to apply righteous judgments. Doing justice is applying a righteous judgment: “By justice [i.e., by applying righteous judgments] a king builds up the land” (Prov 29:4).

Furthermore, context is important for understanding what justice requires.

doing justice = righteous judgment + context

For instance, in the context of a courtroom, justice doesn’t show partiality or accept bribes (Deut 16:19–20). In the context of a marketplace, justice uses “a just balance and scales” (Prov 16:11).

Justice according to the Bible contrasts with justice according to our secular age in which justice = rights. Our secular age offers the fruit without the root—the fruit of rights without any standard of righteousness for measuring which rights are right. As such, people learn to enshrine whatever they want with the language of rights. Justice effectively becomes “I deserve what I want,” with the one proviso that others’ rights should not be transgressed either, leaving a muddled mess for the courts to sort out amid the myriad conflicts that inevitably arise. So if a man wants to marry a man, it is his right. “Justice” demands it. If a woman wants to terminate her pregnancy, it is her right. “Justice” demands it. If a man decides he wants to have surgery to become female, “justice” demands it. If a person wants to pursue euthanasia and “die with dignity,” “justice” demands it. Whether or not this definition of justice is the best we can do in a pluralistic nation, we can leave for another day. The point here is to observe the difference between a biblical view of rights and contemporary Western culture’s view. Sometimes justice-as-rights will yield just outcomes by the biblical standard (e.g., the right to religious freedom). Sometimes it yields very unjust outcomes by the biblical standard (e.g., the above examples).

2. Christians passionately care about justice. Why? Because justice characterizes God: “he has established his throne for justice” (Ps 9:7); he practices and delights in justice and righteousness (Jer 9:24); “every morning he shows forth his justice” (Zeph 3:5); “righteousness and justice are the foundation of [God’s] throne” (Ps 89:14); he “is exalted in justice” (Isa 5:16). And the just God has justified Christians. Justification is to justice what faith is to good works. Genuine faith results in good deeds, and doing good deeds gives evidence of genuine faith (Matt 7:15–20; James 2:14–26). Similarly, being justified results in a desire to do justice, and doing justice gives evidence of being justified.5

3. Governments exist for the purpose of justice. God instituted governments to do justice for everyone created in his image (Gen 9:5–6; Rom 13:1–7; cf. 2 Sam 8:15; 1 Kgs 10:9; Prov 29:4). So when Christians talk about abortion, immigration, poverty, or same-sex marriage, they are fundamentally talking about doing justice and opposing injustice. Subcategories of justice include procedural justice (how a society makes fair decisions), retributive justice (how to fairly punish criminals), and distributive justice (how the government distributes or redistributes its nation’s resources). The most controversial subcategory these days is social justice, which speaks to societal structures broadly and includes elements of the other subcategories of justice.

Christians might debate how to define and evaluate social justice, but it has provided a category that some modern American Christians may not have had: individuals are not the only ones who can be unjust; systems can be, too. Legal and social structures can be unjust. Sinful people pass sinful laws and support sinful institutions and social practices. Haman convinced King Ahasuerus to enact a genocidal campaign against the Jews (Esth 3:7–14). What started as the sin of two individuals quickly became institutional: it became something bigger than individuals, something institutional, something no individual could stop. Isaiah warned against “iniquitous decrees” and “writers who keep writing oppression, to turn aside the needy from justice and to rob the poor of my people of their right” (Isa 10:1–2). Jesus condemned the experts in the Mosaic law for loading burdens on people that were too hard for them to bear (Luke 11:46). And the first church unjustly neglected the widows of Greek-speaking Jews (Acts 6:1).

Politics yields passionate disagreements between Christians, then, whenever both sides disagree about how to apply God’s word—that is, they disagree about what justice requires. The other side looks like it’s promoting an injustice, which in turn can tempt people to question whether the other side is actually Christian.

4. In our political context, people on the Right and Left tend to emphasize different aspects of the government’s work of dispensing justice. People on the Right tend to emphasize justice as righteously punishing wrongdoers, while people on the Left tend to emphasize lifting up the wronged. We believe the Bible emphasizes both: “May [the king] judge your people with righteousness, and your poor with justice! … May he defend the cause of the poor of the people, give deliverance to the children of the needy, and crush the oppressor!” (Ps 72:2, 4).

5. Christians passionately believe that their political convictions promote justice. People may often be right in their opinions and in their politics. At the same time, the fallen heart always thinks it’s right; it always thinks its cause is just. Adam and Eve’s decision to partake of the fruit required a self-justifying argument, and we have all been self-righteous and self-justifying ever since. And self-justifying people tend to be certain that their convictions are just. That’s why we are tempted to scorn and second-guess our fellow church members whose politics disagree with ours.

So the first reason Christians passionately disagree over politics is that Christians passionately care about justice and believe that their political convictions promote what they perceive as justice. The second is like it.

1.2. Because Christians Have Different Degrees of Wisdom for Making Political Judgments and Tend to Believe That They Have More Wisdom Than Those Who Differ

Most political judgments depend on wisdom, and only God is all-wise. Political judgments are difficult because we all lack wisdom to various degrees. Even if Christians agree on biblical principles, they will often disagree over methods and tactics and timing and more.

Wisdom is both a posture and a skill. It’s the posture of fearing the Lord, and it’s the skill of making productive and righteous decisions. Life is full of complex, complicated decisions; wise people skillfully apply the Bible because they fear the Lord. Wisdom recognizes that there’s a time to answer a fool according to his folly and a time to refrain (Prov 26:4–5). Like cars need fuel, political judgments need wisdom.

Consider once more the episode of the two prostitutes each telling King Solomon that the baby was hers. Solomon called for a sword and commanded, “Divide the living child in two, and give half to the one and half to the other” (1 Kgs 3:25). That revealed the real mother. And it required wisdom: “And all Israel heard of the judgment that the king had rendered, and they stood in awe of the king, because they perceived that the wisdom of God was in him to do justice” (1 Kgs 3:28). The goal was justice; the means was wisdom.

The goal of politics is justice; the means is wisdom. Five examples may help illustrate that most controversial political issues depend on wisdom: abortion, immigration, tax rate, political alliances, and political parties.

Example 1: abortion. The Bible forbids abortion since deliberately killing an unborn person is a form of murder. Preachers and churches, therefore, should take a stand on abortion, both in their preaching and in their membership decisions. They should excommunicate anyone who unrepentantly promotes abortion, whether by personally encouraging women to seek them or by politically advocating for abortion.6

But Christians do not agree on all the political tactics for opposing the injustice of abortion. Some Christians take an incrementalist strategy. They advocate for policies that prohibit abortion with the exceptions of rape and incest because they think such policies stand a better chance of passing and that they will eliminate the vast majority of abortions. Others reject such an incrementalist strategy as compromising. Instead, they take an all-or-nothing approach. Who is right strategically? It’s hard to be certain, of course, because we’re relying on our own wisdom. The Bible might have principles to bring to bear, but it doesn’t speak directly to political tactics like that. That’s why Pastor Mark Dever, for instance, told me (Jonathan) that he would say that he won’t promote a pro-life march from the pulpit even though he might participate in one. He does not want to use his pastoral authority to communicate that Christians must adopt the political strategy of marches. Marches may or may not be wise. The Bible doesn’t come close to saying, and a pastor’s authority depends on the Bible.

Example 2: immigration. Consider the controversy surrounding Central and South American asylum seekers and other migrants crossing the southern United States border. One group of Christians believes the present laws are just fine. If anything, they believe we need to tighten the restrictions in order to protect our nation and our children. Another group of Christians argues that humanitarian considerations mean allowing as many migrants in as the present law allows, or even changing the laws to accommodate more. And let’s agree that “protecting our children” and “showing compassion to asylum seekers” are both biblical impulses. Still, there’s a long way to travel between affirming those two biblical principles and determining how to balance them in public policy. How many migrants should a nation permit a year? How many asylum seekers? How will that affect the economy and people’s livelihoods? What is the best way to prevent and combat drug and human trafficking? Is a nation obligated to undertake all the costs of processing the hundreds of thousands of migrants who might show up at the borders? In what kinds of conditions should refugees be housed at the border? What about child-parent separation? What unintended consequences might follow this decision or that decision?

Answering those tough questions requires wisdom. The revealed wisdom of God in the Bible is distinct from the wisdom of man, which we need to make nearly every political judgment. Political judgments depend on figuring out how to apply the Bible to the vast and complex set of circumstances that surround every political decision. They require a person to rightly understand biblical principles and then to apply those principles based on social dynamics, legal precedent, political feasibility, historical factors, economic projections, ethnic tensions, criminal justice considerations, and so much more.

When you feel anger at what you perceive to be a political injustice such as an aspect of immigration, you are applying your wisdom to an issue. You are responding with negative moral judgment against what you perceive to be injustice. But it’s possible for you (1) to make a political judgment that lacks wisdom and (2) to respond sinfully to what you perceive.

Example 3: tax rate. Christians agree that the Bible condemns stealing. Some infer that a progressive income tax is unjust because it arises from coveting the wealth of the rich and therefore amounts to stealing. Saying the rich need to pay their “fair share” doesn’t offer a standard by which to judge what counts as “fair.” Others argue that a progressive income tax is better than a flat tax since Jesus said, “Everyone to whom much was given, of him much will be required” (Luke 12:48). It is “fair” because they don’t deserve the extra they have. The first group says that passage has nothing to do with tax rates, and the second group says it applies to all of life. Back and forth it goes. Christians make different political judgments.

Example 4: political alliances. If you want to get things done in a democratic system, you have to make alliances with people with whom you don’t agree on everything. That’s why political parties exist. There are not enough people who think exactly like we do on every issue, so we have to join together with people who agree with us on a significant clump of issues to get anything done.

But this process of forming political alliances raises moral questions. Are we culpable for any unjust legislation the other members of our political party manage to pass into law? What if the other party does even more injustice? Does it make a difference if the injustice we’re talking about is a “small injustice” versus a “big injustice”—and how big is big? Does it make a difference if we’re comparing evil rhetoric versus evil policies? And what if one alliance makes us Christians and our witness look hypocritical, while the other means siding with those who explicitly oppose us? We need wisdom!

Example 5: political parties. To complicate matters, the political landscape keeps changing. It may be reasonable for a Christian to support a particular political party today but not a decade later. The ground can shift beneath our feet quickly. Imagine that you lived in Germany in the early 1920s, and a Christian friend told you that he joined the National Socialist Germany Workers Party—the Nazis. You would have misgivings, but your church probably wouldn’t excommunicate him. By the early 1930s, however, what the Nazi Party represented would have become clear enough that voices in your church hopefully would argue for excommunication, as evidenced by the 1934 Barmen Declaration in which the Confessing Church publicly denounced all Nazism. How much more would this be the case by the 1940s? Politics are not static, and with every passing day we need a fresh dose of wisdom. And Christians will have different opinions all along the way.

For example, the political landscape in the United States has changed radically in the last few decades, and with every passing year more and more elements in both parties challenge the biblical standards of justice. The Republican Party has demonstrated a tendency toward an amoral libertarianism, which can function according to the utilitarian principle of sacrificing the few for the sake of the many. Its good emphasis on individual responsibility can overlook larger structural realities and deny implicit biases and thus leave behind the poor, the foreigner, or the minority. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has adopted shockingly extreme views on abortion by doubling down on third-trimester abortions and sometimes commending a woman’s “choice” to kill an accidentally delivered child. The Party also champions gay “marriage,” transgender “rights,” and other LGBTQ+ “rights” in the name of tolerance in a way that punitively threatens the religious liberty of evangelical institutions such as churches, schools, and adoption agencies.

We list problems in both parties not to suggest there is a moral equivalence between them. We don’t believe there is. Some evils are greater than others.

Looking at the landscape in the United States today, some Christians seem untroubled by their choice of party. Others don’t feel fully aligned with either party but say they hold their noses and pick “the lesser of two evils.” Still others wonder if one or both of the major parties have become off limits for Christians, like the situation with the Nazi Party. We don’t think that a particular political party is a perfect fit for a Christian.7 If we did, then party thinking would probably be subverting our Christianity. But we do not believe in moral equivalency. Some parties are better than others, and some injustices are worse than others.

Yet our goal throughout this article is not to assess the landscape or to tell you which political judgments to make on any given political matter. Rather, it’s to encourage you to ask God for wisdom and then to remember that neither you nor your fellow church members are Solomon, much less Jesus, who alone is perfectly wise. Remembering this should create some room for charity and forbearance.

We resonate with theologian and ethicist John Frame that political choices are not always obvious:

It is an art to weigh the importance of different issues and to come to a godly conclusion. Each of us should have a large amount of tolerance for other Christians who come to conclusions that are different from ours. Rarely will one issue trump all others, though I must say that I will never vote for a candidate who advocates or facilitates the killing of unborn children.8

2. Why Must Christians Agree to Disagree over Jagged-Line Political Issues?

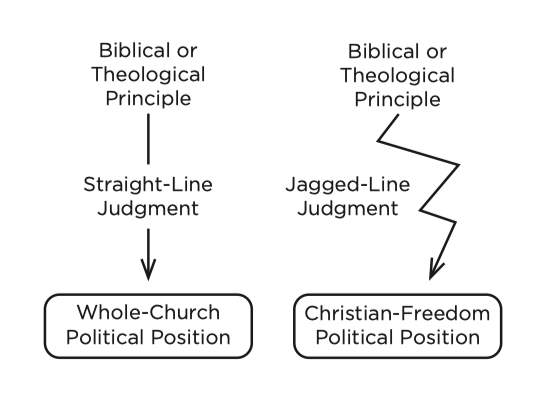

Before we answer that question, we must first explain jagged-line vs. straight-line political issues. For a straight-line issue, there is a straight line between a biblical text and its policy application. For instance, the Bible explicitly teaches that murder is sinful; abortion is a form of murder, so we should oppose abortion. That’s a straight line. Accordingly, both of our churches would initiate the church-discipline process with a member who is advocating for abortion—such as encouraging a single pregnant woman to get an abortion or supporting Planned Parenthood. Though we do not affirm the gospel faithfulness of Roman Catholic Churches, we do appreciate the occasional news report of a Roman Catholic bishop denying communion to politicians such as Ted Kennedy and Joe Biden.

For a straight-line issue, there is a straight line from a biblical or theological principle to a political position. But for a jagged-line issue, there is a multistep process from a biblical or theological principle to a political position. Fellow church members should agree on straight-line political issues, and they should recognize Christian freedom on jagged-line political issues. (See Figure 1.)

Most political issues are not straight-line issues. Most are jagged-line issues. Think of everything from trade policy to healthcare reform to monetary policy to carbon dioxide emission caps. These issues are important, and Christians should bring biblical principles to bear when thinking about them. But the path from biblical text to policy application is not simple. It’s complex. For such issues, none of us should presume to possess “the” Christian position, as if we were apostles revealing true doctrine once and for all time. Rather, we should recognize that such issues belong to the domain of Christian freedom (see sections 2.1 and 3.1 below).

This distinction between straight-line and jagged-line issues comes from Robert Benne, a conservative Lutheran scholar who specializes in how Christianity relates to culture. In his book Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, he argues that treating most issues as straight-line harmfully fuses what is central and essential to Christianity with particular political policies.10 And both sides of the political spectrum, Benne observes, can fall into this error. Paul Tillich drew a straight line from Christianity to the political-economic system of socialism. Meanwhile, the Christian Coalition, by placing “Christian” in their name, could imply that those who disagree with their political policies are not Christians. Benne recognizes that Christians often employ straight-line thinking unintentionally: “Many individuals and churches are so deeply committed to the affinity of their faith convictions with particular political philosophies and programs that they de facto fuse the faith and politics.”11 The policies that mainline Protestant churches in America prefer “seem to mimic those of the Democratic Party,” while the Religious Right seems to move in a straight line “from central core convictions to conservative policies.”12 But, argues Benne, “The trajectory from core Christian theological beliefs to a specific public policy is a complex and jagged one.”13 Relatively few political issues are straight-line issues. Benne names a handful of them:

- “policies that restrain abortion”

- “policies that uphold classical views of marriage”

- the cluster of issues “surrounding a ‘safety net’ for the most vulnerable in our society” (Benne qualifies, “Even these relatively straight-line trajectories do not lead necessarily to specific public policies.”)

- the cluster of issues of protecting “religious liberty at home and abroad”

- opposing policies “that do not jibe with any line from the core to public policy” such as “Hitler’s genocidal policies”14

To that list of straight-line issues, we would add that Christians should oppose policies that support prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against people on the basis of their race or ethnicity—as if some people are not made in God’s image.

The problem with saying there is a straight line from the Bible to specific policies is that while the goal (pursued by the policies) may be a straight line, the policies may not. Benne argues that for most political policies, “the steps between core and policy are so fraught with disagreement that clear connections are impossible. A whole range of public policy issues—perhaps the vast majority of them—exhibit a tangled journey from core to policy. There simply are too many steps in the movement from core to public policy, involving too many prudential judgments, to construct anything like a straight line”—such as addressing foreign policy in Iraq, the economic recession, or global warming.15 As John Frame asserts, “When issues become more specific, it often becomes more difficult to be sure of the biblical position”16—or whether there even is the biblical position.

In short, it is critical to distinguish between straight-line issues (which can lead to what we might call the Christian position) and jagged-line issues (whose policy judgments belong to the domain of Christian freedom). It’s right for churches to take institutional stands on straight-line issues through preaching and membership decisions, but church leaders risk being sinfully divisive by taking those institutional stands on jagged-line issues.17

Now that we’ve explained jagged-line vs. straight-line political issues, we are ready to answer the question Why must Christians agree to disagree over jagged-line political issues? For at least two reasons: (1) Christians must respect fellow Christians who have differently calibrated consciences on jagged-line issues, and (2) insisting that Christians agree on jagged-line issues misrepresents Christ to non-Christians.

2.1. Because Christians Must Respect Fellow Christians Who Have Differently Calibrated Consciences on Jagged-Line Issues18

Yes, must. It’s not optional to respect fellow Christians who have differently calibrated consciences on jagged-line issues. Jagged-line issues correspond to what Paul in Romans 14:1 calls “disputable matters” (NIV) or “opinions” (ESV) or matters of conscience. “Don’t argue about disputed matters” (CSB).

Your conscience is your consciousness of what you believe is right and wrong. That implies that your conscience is not necessarily correct on every issue. What you believe is right and wrong is not necessarily the same thing as what God believes is right and wrong. You might believe with deep conviction in your conscience that a ten-year-old boy has the right to choose to become a biological female. If so, your conscience is not functioning correctly for that issue because it is based on immoral standards. You should calibrate your conscience.

The idea of calibrating your conscience pictures your conscience as an instrument. Instruments can be incorrect: your bathroom scale may say you weigh 142 pounds when you actually weigh 139; your car odometer may indicate that your speed is 52 when it’s actually 56; your watch may say it is 1:47 PM when it’s actually 1:49 PM. When an instrument is incorrect, it needs to be calibrated. To calibrate an instrument is to align it with a standard to ensure that it’s functioning accurately.

The standard for what’s right and wrong is God, who has revealed himself to us particularly through the Bible. So when your conscience is not functioning accurately, you should endeavor to align it with God’s words. The classic example of this in the Bible is the Apostle Peter. He was convinced in his conscience that it was sinful to eat certain foods—like pork. God told Peter three times to “kill and eat” animals that Peter considered to be unclean. Peter had the gall to reply to God, “By no means, Lord; for I have never eaten anything that is common or unclean.” But because the Lord was commanding Peter to eat those foods, Peter had to calibrate his conscience so that he would have the confidence to accept food and people that he previously could not accept (see Acts 10:9–16).

So how does a Christian calibrate his or her conscience? In at least three ways:

1. by educating it with truth. Truth refers primarily to the truth God reveals in the Bible, but it also includes truth outside the Bible. For example, assuming that God allows some forms of contraception, the decisive information that may lead a Christian couple to use or not use a particular form of contraception may be truth outside the Bible—that is, scientific information that explains in detail how a form of contraception works.

2. in the context of your church. Godly church leaders and fellow members are one of God’s gifts to you to help you calibrate your conscience. You don’t have to do it alone.

3. with due process. Some issues may take you years to work through. That’s okay. It’s better not to rush it than to prematurely change and go against your conscience.

How does all this relate to jagged-line political issues? Here’s the basic scheme that we’re recommending: Treat straight-line issues as whole-church issues, and treat jagged-line issues as Christian-freedom issues or matters of conscience. It’s critical that Christians distinguish between straight-line whole-church issues and jagged-line Christian-freedom issues because the consciences of Christians should function differently for each set of issues. For straight-line whole-church issues, pastors should preach, “This is what God says.” It’s right to try to persuade people to be conscience-bound on whole-church issues. Furthermore, straight-line or whole-church issues will impact membership decisions. An abortion doctor or a member of the Ku Klux Klan could not be a member of either of our churches. Those are both straight-line issues, which means they are whole-church issues.

Jagged-line issues are matters of conscience that fellow church members should be able to agree to disagree over. Disputable matters include issues such as how you interpret who “the sons of God” are in Genesis 6 or how Christians should view the “Sabbath.” It also includes the vast majority of political judgments. For example, is the American government presently enforcing the death penalty in a just way? If not, what are the next steps the government should take to solve that problem?19

Jagged-line issues easily become deeply ingrained in your conscience. And that sets the scene for conflict because we inevitably dispute disputable matters. No two sinful humans agree on absolutely everything—not even a godly husband and godly wife. We have different perspectives, backgrounds, personalities, preferences, thought processes, and levels of understanding truth about God, his word, and his world. So it’s not surprising when fellow church members disagree about jagged-line issues. We should expect that and learn to live with those differences. We don’t always need to eliminate such differences, but we must seek to glorify God by loving one another in our differences. That is Paul’s main concern in Romans 14.

Here are two of Paul’s principles in Romans 14:

1. Welcome those who disagree with you as Christ has welcomed you (Rom 14:1–2; 15:7). Those who have a weak conscience on a particular issue are theologically incorrect but not heretical since the issue is not “of first importance” (1 Cor 15:3). Your main priority should not be for them to change their view. Your main priority is to “welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you, for the glory of God” (Rom 15:7).

2. Don’t look down on those who are stricter than you on a particular issue, and don’t be judgmental toward those who have more freedom on a particular issue (Rom 14:3–4). Love those who differ with you by respecting them, not disdaining them. Don’t assume that anyone who is stricter than you is legalistic or that anyone who is freer than you is licentious. When you are convinced that a certain political strategy is just, you may be tempted to treat it as a matter of first importance, but that would be a grave mistake because it would imply that those who disagree with you on that issue cannot be Christians.

So is it okay to talk about jagged-line political issues with fellow Christians? Yes, but only if you do it with the right spirit and with the right proportion. Be strict with yourself and generous with others. Genuinely respect your fellow brothers and sisters who disagree with you on jagged-line political issues. Don’t become preoccupied with jagged-line issues with the result that you are divisive about them. Jagged-line issues should not be so important to you that it’s all you want to talk about.

The same is true, of course, in other areas. We both have an opinion of the nature of the millennium. And both of us would be willing to share our opinion about the millennium, say, in a Sunday School class. Still, when I (Jonathan) was teaching about the millennium in such a setting, I told the class that they could disagree with me and still be a member of the church. I would not make this a point of contention and division. I treat that topic differently than I treat a gospel issue like the Trinity or even a church-order issue like baptism. We have to agree on gospel issues and church-order issues. They are whole-church issues. We don’t have to agree on conscience issues.

Christians must agree to disagree over jagged-line political issues because of how God commands Christians to relate to fellow Christians—respect those with differently calibrated consciences. A second reason concerns how Christians relate to non-Christians.

2.2. Because Insisting That Christians Agree on Jagged-Line Issues Misrepresents Christ to Non-Christians

When a Christian insists that his conviction about a jagged-line political issue is the Christian position, he is misrepresenting Christ to non-Christians. We cringe when we see this on social media. A well-intentioned brother links to a partisan opinion article that implies his policy position on immigration (or global warming or poverty or gun rights or systemic racism) is the Christian position—the position that Jesus himself demands his followers take—and that those who oppose his conviction are unbiblical and unchristian. Sometimes, he might be right. Often, he isn’t. And that creates a poor witness to non-Christians, who consequently might equate Christianity with a specific political position or political party.20 We don’t want to imply that the Bible requires you to take a particular view on a jagged-line political issue to be a Christian. That does not accomplish the church’s mission (more on that in section 3.2 below).

The gospel creates a unified people in Christ, but it does not necessarily create political uniformity for wisdom-based political judgments. Churches should strive to proclaim the gospel to as many people as possible—people who are diverse economically, generationally, ethnically, and nationally. Churches must be careful not to cultivate a culture that pressures everyone in the church to be uniform on jagged-line issues. Christians must not bind the consciences of fellow Christians on disputable matters. Even if your church is healthy, your members will likely not be entirely uniform in their politics. There may be some political tension. That’s okay because what unites us is our love for Jesus, not our convictions on jagged-line political issues. And when your church cultivates a healthy unity amid such diversity, that strengthens how you represent Christ to outsiders. What marks Christians should be our love for one another—not our strident tone.21

It makes sense that you may feel skeptical or angry toward fellow church members when they disagree with you about which political judgments are the most just. But that doesn’t make it right. You must love and respect your fellow church members who differ with you on jagged-line issues.

3. How Must Christians Who Disagree over Jagged-Line Political Issues Agree to Disagree?

Christians who disagree with one another over jagged-line political issues must agree to disagree in at least three ways: (1) by acknowledging leeway on jagged-line political issues, (2) by uniting to accomplish the mission Christ gave the church, and (3) by prioritizing loving others over convincing them that your convictions about jagged-line political issues are right.

3.1. By Acknowledging Leeway on Jagged-Line Political Issues

Christians must distinguish between the Christian position on a political matter (e.g., abortion) and political matters that are jagged-line issues (e.g., carbon dioxide emission ceilings, national math standards for eighth graders, the existence of a federal aviation authority, and requirements on commercial airline construction). There’s no leeway for straight-line issues; there is leeway for jagged-line issues. (Leeway refers to space for Christians to have different opinions.)

If there is no leeway according to the Bible for Christians to disagree, then pastors should preach about those matters from the Bible as the Christian position, and that should affect whom churches admit into their membership and whom they remove from membership. If there is leeway for Christians to disagree, then pastors should not attempt to bind consciences on such issues, and a Christian’s position on such issues should not affect his or her standing as a church member. We must distinguish (1) what God says and (2) our political judgments on jagged-line issues that apply what God says. For example, determining the most strategic way to vote is ordinarily a jagged-line issue.22

It’s one thing to believe that God forbids stealing. That’s what God says in the Bible. But it’s another thing to argue that a ninety percent tax rate, which was the rate in 1960 for anyone making more than $300,000 in the United States, is stealing. That’s a political judgment on a jagged-line issue that applies what God says. We personally think that that political judgment is probably correct, and we’re even happy for Christians to attempt to persuade one another on the topic, particularly as some Americans increasingly regard socialism as a viable option. But we must be careful not to imply that the way we apply the Bible here is the Christian position. There’s a big difference between titling your position paper “The Christian Statement on Tax Rates” and “A Christian Statement on Tax Rates.”

Ethics professor Andrew Walker proposes a helpful “ethical triage”: (1) must = obligatory; (2) should = advisable; and (3) may = permissible.23 That’s a helpful grid for thinking through political matters. It’s sinful to adopt a take no prisoners strategy for a jagged-line political issue that’s actually a “should” at best and more likely a “may.”

One of my (Jonathan’s) pastor friends wisely observed, “I thought my job as a pastor would focus on getting my church members to encourage one another to do what the Bible commands. Instead, most of my job is keeping my church members from demanding things of each other the Bible never does.” We need to be able to simultaneously work to persuade one another of perceived injustices while also leaving one another some measure of freedom to disagree about what counts as an injustice.

Here’s some advice to pastors: Be cautious about how you wield your influence on jagged-line political issues. Your job is to preach the Bible—not to advocate specific political policies. Your authority is tied to God’s word. So when you preach and teach and counsel your flock, be very careful not to speak about jagged-line political issues with the same conscience-binding authority with which you speak about matters “of first importance” (1 Cor 15:3). When you speak dogmatically about a jagged-line political issue, you weaken your ability to prophetically address a straight-line political issue.24

A U. S. senator once invited his pastor, Mark Dever, to his office for advice on a constitutional amendment that would require a balanced budget. The senator shared, “My colleagues are pushing me. The party whip is pushing me. The press is hounding me. You’re my pastor. How should I vote?” Dever wisely responded, “Brother, I’ll pray that God gives you wisdom.” And that was all. Years later, Dever recounted to me (Jonathan), “It’s not like I didn’t have an opinion. I had a very strong opinion.”

I asked, “So why didn’t you say something?”

“Because my authority as a pastor,” Dever explained, “is tied to the word of God. I know I’m right about the Bible. I know I’m right about the gospel and Jesus’s promised return. And I’m happy to address any political issue that meets the criteria of being biblically significant and clear. I don’t think the constitutional amendment in question was either biblically clear or significant. Therefore, I’m going to preserve my pastoral authority and credibility for what Scripture has told me to talk about.” To be sure, some people might argue that the balanced budget amendment is biblically clear or significant. Fine. That was a judgment call on Dever’s part. Our goal isn’t to argue about that issue; it’s to commend the principle that Dever illustrates. He distinguished between straight-line and jagged-line issues, and he humbly practiced forbearance with jagged-line issues, particularly as a pastor.

Dever also explained that if the senator asked him about the 13th amendment (outlawing slavery), the 14th amendment (the right of citizenship for all races), or the 15th amendment (voting rights for all races), he certainly would have spoken up since the line from the Bible to political policies is straighter for those issues. Those who are justified will pursue justice. Faith shows itself in deeds.25

More and more, the two of us find ourselves in conversations with brothers and sisters in Christ who feel stuck. They “cannot possibly imagine” voting for this party or that party or either party. Yet hopefully you can now better understand what it would mean to treat this kind of question as a straight-line whole-church issue: it would mean your church would potentially excommunicate anyone who supports this or that party, even as we would excommunicate a Nazi. Until your church reaches that point, you must exercise some measure of charity and forbearance.

Churches can sin and prove faithless by not speaking up in matters of political policy when they should. But only once in a great while should churches speak directly to political policy or to particular candidates. Normally doing that would require competencies that most pastors don’t possess, and it would be saying more than Jesus authorizes pastors to say.

3.2. By Uniting to Accomplish the Mission Christ Gave the Church

The distinction between straight-line versus jagged-line issues needs to be set inside the larger conversation about the mission of the church. God gives everyone jobs to do, including the different institutions he has established like governments, churches, church elders, or parents. If two Christians disagree whether X is a part of the church’s job, one is bound to argue, “Why are you saying the church should take a stand here? This isn’t any of the church’s business!”

Part of Christians learning how to agree to disagree better than we presently are, therefore, is trying to come to some agreement on what exactly is the church’s “business.” What jobs has God given it? What is its mission?

We implicitly assume throughout the previous section (3.1) that straight-line issues are a part of the church’s business—at least in its capacity as a corporate actor—while jagged-line issues are not. Instead, jagged-line issues are the prerogative of church members or individual Christians.26

The problem is that most Christians have little ecclesiology. They have little understanding of the institutional authority and concreteness of a church and how the individual Christian and his or her opinions are not the same thing as a church and its authority. The individual Christian walking into the public square is not the same thing as a church collectively walking into the public square.

The individual Christian stepping into the public square should make every use of common-grace knowledge, his or her own study of the Bible, and even partnerships with non-Christians to advocate for just ends on every straight-line or jagged-line issue out there. They possess much more freedom to speak to a broad range of issues, so long as they take care not to treat their positions as “the” biblical or “the” Christian position, save those on which their church has rendered judgment.

God has commissioned local churches, acting corporately, to teach everything Jesus commanded and to equip the saints for their respective ministries. But God has not commissioned local churches to advocate across the whole range of issues that comprise the work of government. It’s not a part of their job. It doesn’t belong to their mission. They can teach what the Bible says about taxes and private property. They probably shouldn’t presume to speak to this or that tax bill. We might say that the church is to an individual church member what a law school is to a lawyer or a medical school is to a doctor. The law school’s “mission,” for instance, is to teach law to the aspiring lawyer, whose “mission” in turn is to practice law. The two missions work together, but they are distinct.

What will help Christians to agree to disagree politically, in short, is pastors who begin to teach their members what a church is, what the church’s corporate mission is, and how that mission differs from the mission God has given them as individual church members. With these distinctions more firmly in mind, we believe one church member should more easily be able to say to another member, “Well, I feel strongly about this political issue, and I disagree with you. But I recognize that we can still share the Lord’s Supper together in love and peace amid our disagreements. Our agreement on this topic is not what makes us a church.”

3.3. By Prioritizing Loving Others Over Convincing Them That Your Convictions about Jagged-Line Political Issues Are Right

That’s Paul’s burden in Romans 14. It’s ideal that you not have a theologically incorrect position (i.e., a weak conscience) on a disputable matter. But far more important than eliminating disagreements on such issues between fellow church members is that fellow church members love one another in their differences.

We are not suggesting that you never talk about controversial political issues with fellow church members or that you never make a case for why you are convinced that your political judgments promote justice. We are exhorting you to prioritize loving fellow Christians over convincing them that your convictions about jagged-line political issues are right. Here are six specific ways to love one another:

1. Welcome those who disagree with you as Christ has welcomed you (Rom 14:1; 15:7). Treat brothers and sisters who disagree with you over politics as family—not as enemies. View them with an eternal perspective. To cultivate that mindset, meditate on eternity and the final judgment. That shouldn’t cultivate complacency or indifference toward injustice; it should calibrate your perspective over politics and fellow Christians who disagree with you on specific political policies. Measure the now according to the eternal then.

2. “Be quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger” (James 1:19). Why? “Because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires” (James 1:20 NIV). Sinful anger overreacts and escalates controversy and tension. Wise Christians know when and how to dial down the temperature of political disagreements.27

“A fool takes no pleasure in understanding, but only in expressing his opinion” (Prov 18:2). Humbly listen to those who don’t share your perspective, especially when they come from a different background.28 Put yourself in their shoes. What principle of justice are they seeing that you might be missing? Don’t assume that you flawlessly perceive injustice.29 Be sensitive to the fears and concerns of fellow believers whether you agree or not.

3. Pray with affection for those who disagree with you. When you pray about the outcome of someone else’s faith, God often deepens your affection for them. When fellow church members celebrate Bible teachings that are of first importance, jagged-line issues shouldn’t overthrow those rich truths we love and live for and would die for.

4. Respectfully think about those who disagree with you. Don’t disdain them or look down on them. This is not easy to do. It’s not natural; it requires God’s supernatural enabling. The natural route is to avoid the guy who incessantly pontificates about his political hobby horse or to think condescendingly about that lady who is too far to the right or too far to the left. You might be tempted to suspect that a fellow member may be an enemy because he voted for the other side and thus may not even be a genuine Christian. “Slander no one … be peaceable and considerate … be gentle toward everyone” (Titus 3:2).

5. Don’t use the label gospel issue for a jagged-line political judgment that you think is an implication of the gospel.30 Calling something a gospel issue sounds the theological alarm at DEFCON 1. It may communicate something like this: “I hold the Christian position on this political matter. If you don’t agree with me, then you are not a Christian.” We agree with Tim Keller that evangelism and our pursuit of justice “should exist in an asymmetrical, inseparable relationship.”31 In other words, there is an inseparable asymmetry between the primary problem the gospel solves (our sin against God) and the secondary problem the gospel solves (our sin against others); one way we preserve the gospel is by giving grace and protecting Christian liberty on jagged-line political matters.32

6. Exult with one another that we can trust our sovereign God when politics tempt us to be sinfully anxious.

Our God is in the heavens;

he does all that he pleases. (Ps 115:3)

Why do the nations rage

and the peoples plot in vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers take counsel together,

against the LORD and against his Anointed, saying,

“Let us burst their bonds apart

and cast away their cords from us.”

He who sits in the heavens laughs;

the Lord holds them in derision. (Ps 2:1–4)

Do not be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble. (Matt 6:34)

4. Concluding Prayer

Father, when we disagree with one another on complex political issues, would you please help us disagree in a way that pleases you? Give us courage to be faithfully countercultural and to represent you truthfully to non-Christians. Please give us wisdom to love and forbear when we disagree about political judgments. Please unite us to accomplish the mission Christ gave the church. We ask this for the fame of your Name. Amen.

[1] Thanks to friends who examined a draft of this article and shared helpful feedback, especially Anthony Bushnell, Brian Collins, Sam Crabtree, J. D. Crowley, Kevin DeYoung, Abigail Dodds, Collin Hansen, Tim Keesee, James McGlothlin, Travis Myers, Charles Naselli, John Piper, Joe Tyrpak, Mark Ward, Steve Wellum, Jonathon Woodyard, Mike Wittmer, and Fred Zaspel.

We recently coauthored a little book that overlaps with this article: Jonathan Leeman and Andrew David Naselli, How Can I Love Church Members with Different Politics?, 9Marks (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2020). In that book we target laypeople, and in this more academic article we target church leaders (e.g., the book contains no footnotes).

[2] E.g., see John Piper, “What Do Christians Care About (Most)?,” 17 May 2019, https://www.desiringgod.org/messages/what-do-christians-care-about-most.

[3] The typical way dictionaries define politics concerns publicly distributing power over an entire population—e.g., “the activities associated with the governance of a country or other area, especially the debate or conflict among individuals or parties having or hoping to achieve power” (The New Oxford American Dictionary [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017]). For a chapter-length discussion on how to define and describe politics, see Jonathan Leeman, Political Church: The Local Assembly as Embassy of Christ’s Rule, Studies in Christian Doctrine and Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016), 55–97. In this article we are thinking of politics primarily in the democratic republic of the United States because that is our context, but what we write applies in principle to other governments.

[4] Scripture quotations are from the ESV, unless otherwise noted.

[5] Cf. Andrew David Naselli, “The Righteous God Righteously Righteouses the Unrighteous: Justification according to Romans,” in The Doctrine by Which the Church Stands or Falls: Justification in Historical, Biblical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspective, ed. Matthew Barrett (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), 209–33.

[6] On church membership and excommunication, see Jonathan Leeman, Church Membership: How the World Knows Who Represents Jesus, 9Marks (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012); Jonathan Leeman, Church Discipline: How the Church Protects the Name of Jesus, 9Marks (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012).

[7] Cf. Timothy Keller, “How Do Christians Fit Into the Two-Party System? They Don’t,” The New York Times, 29 September 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/29/opinion/sunday/christians-politics-belief.html.

[8] John M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Christian Life, A Theology of Lordship (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2008), 617.

[9] This figure is from Leeman and Naselli, How Can I Love Church Members with Different Politics?, 41. Used with Crossway’s permission.

[10] Robert Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010), 31–38.

[11] Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, 35.

[12] Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, 37.

[13] Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, 71.

[14] Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, 76–78.

[15] Benne, Good and Bad Ways to Think about Religion and Politics, 78–79.

[16] Frame, The Doctrine of the Christian Life, 617.

[17] Cf. John S. Feinberg and Paul D. Feinberg, Ethics for a Brave New World, 2nd ed. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 721–23. The Feinberg brothers make three distinctions: “(1) prescriptive versus descriptive language; (2) ethical principles versus prudential advice; and (3) universal general norms versus contextualized specific applications of principles” (722). They argue that political issues don’t have a “Christian position” if Scripture doesn’t directly address them—that is, if they are matters of prudential policy and not scriptural ethics, such as laws about voluntary prayer in public schools (723).

[18] This section condenses Andrew David Naselli and J. D. Crowley, Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2016).

[19] Some readers might be wondering why we are taking a binary approach here (i.e., either whole-church or not; either straight-line or jagged-line) and not using theological triage (i.e., three levels of importance—essential, cardinal doctrines; important denominational distinctives; and nonessential, non-cardinal doctrines). On theological triage, see R. Albert Mohler Jr., “A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity,” Albert Mohler, 12 July 2005, https://albertmohler.com/2005/07/12/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity; Andrew David Naselli, How to Understand and Apply the New Testament: Twelve Steps from Exegesis to Theology (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2017), 295–96; Gavin Ortlund, Finding the Right Hills to Die On: Theological Triage in Pastoral Ministry (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2020). We are not using theological triage here because church organization is binary. To borrow language from Jesus, a church will bind some things and loose others (Matt 16:19; 18:18). The church will decide that belief x or practice y is necessary for being a Christian and church membership or that it is not. More specifically, churches will bind first-tier and second-tier issues but not third-tier ones. Christians will disagree about which issues fall on which side of the whole-church line. Some say a particular view on baptism is a whole-church issue; others don’t. Some say a certain stance on the millennium is a whole-church issue; others don’t. Fine. Our point here is that a line does exist between whole-church issues and Christian-freedom issues and that churches must likewise make membership decisions that are on/off decisions, not three-layered ones.

[20] Cf. how Timothy Keller winsomely explains to a secular audience the difference between big-E Evangelicalism (which the media define sociologically, especially with reference to how people vote) and little-e evangelicalism (which Keller defines theologically, especially with reference to the gospel, the evangel): “Can Evangelicalism Survive Donald Trump and Roy Moore?,” The New Yorker, 19 December 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/can-evangelicalism-survive-donald-trump-and-roy-moore.

[21] On how loving fellow Christians is a powerful way to evangelize non-Christians, see J. Mack Stiles, Marks of the Messenger: Knowing, Living and Speaking the Gospel (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 103–9.

[22] Cf. thought #2 in Kevin DeYoung, “Seeking Clarity in This Confusing Election Season: Ten Thoughts,” The Gospel Coalition, 13 October 2016, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/seeking-clarity-in-this-confusing-election-season-ten-thoughts/.

[23] Andrew T. Walker, “‘Is This a Sin?’: Ethical Triage and Church Discipline,” 9Marks, 2 October 2019, https://www.9marks.org/article/is-this-a-sin-ethical-triage-and-church-discipline/.

[24] For more to pastors along this line, see Kevin DeYoung, “Of Pastors and Politics,” The Gospel Coalition, 3 February 2017, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/of-pastors-and-politics/; Kevin DeYoung, “The Preacher and Politics: Seven Thoughts,” The Gospel Coalition, 1 May 2018, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/preacher-politics-seven-thoughts/; Kevin DeYoung, “The Church at Election Time,” The Gospel Coalition, 3 October 2018, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/church-election-time/.

[25] That story is from Jonathan Leeman, How the Nations Rage: Rethinking Faith and Politics in a Divided Age (Nashville: Nelson, 2018), 145–46.

[26] We won’t take the time here to unpack the broader debate between narrow and broad construals of the church’s mission. Suffice it to say, some (not all) of the confusion roots in the fact that people are using the term church differently when they answer the question about the church’s mission. Advocates of a broad view tend to use the term church to refer to the church as its members. Advocates of a narrow view tend to use the term to refer to the church as a corporate actor. For more on this, see Jonathan Leeman, “Soteriological Mission: Focusing in on the Mission of Redemption,” in Four Views on the Church’s Mission, ed. Jason S. Sexton, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 17–45 (also 92–97, 134–39, 177–82). See also Kevin DeYoung and Greg Gilbert, What Is the Mission of the Church? Making Sense of Social Justice, Shalom, and the Great Commission (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2011); John Anthony Wind, Do Good to All People as You Have the Opportunity: A Biblical Theology of the Good Deeds Mission of the New Covenant Community, Reformed Academic Dissertations (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2019).

[27] When our friend Tim Keesee—a missionary globetrotter—shared feedback on this article, he suggested that we encourage Americans to gain an international perspective on politics: “In much of the world today and throughout history, Christians don’t have any opportunity to impact their government or hold a political opinion that matters. In such countries, justice issues are extremely different than they are in America now. This doesn’t lessen the need to pursue justice in America, but the depth and breadth of systemic injustice is so great in much of the world that it should at least dial down the temperature of our disagreements” (email to Andy Naselli on 16 November 2019, shared with permission).

[28] Cf. Collin Hansen, Blind Spots: Becoming a Courageous, Compassionate, and Commissioned Church, Cultural Renewal (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2015).

[29] Cf. D. A. Carson, How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 160: “When we are convinced that we are suffering unjustly, we may cry out for justice. We want God to be just and exonerate us immediately; we want God to be fair and mete out suffering immediately to those who deserve it. The trouble with such justice and fairness, however, is that, if it were truly just and truly fair and as prompt as we demand, we would soon be begging for mercy, for love, for forgiveness—for anything but justice. For very often what I really mean when I ask for justice is implicitly circumscribed by three assumptions, assumptions not always recognized: (1) I want this justice to be dispensed immediately; (2) I want justice in this instance, but not necessarily in every instance; and (3) I presuppose that in this instance I have grasped the situation correctly.” J. Paul Nyquist presents four reasons that legal justice is elusive: (1) legislative—we make unjust laws; (2) cognitive—we have limited knowledge; (3) spiritual—we have darkened understanding; and (4) neurological—we have implicit bias. Is Justice Possible? The Elusive Pursuit of What Is Right (Chicago: Moody, 2017), 41–89.

[30] See D. A. Carson, “What Are Gospel Issues?,” Them 39 (2014): 215–19. Cf. D. A. Carson, “The Biblical Gospel,” in For Such a Time as This: Perspectives on Evangelicalism, Past, Present and Future, ed. Steve Brady and Harold Rowdon (London: Evangelical Alliance, 1996), 83; Kevin DeYoung, “Is Social Justice a Gospel Issue?,” The Gospel Coalition, 11 September 2018, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/social-justice-gospel-issue/.

[31] Timothy Keller, Generous Justice: How God’s Grace Makes Us Just (New York: Dutton, 2010), 139. Cf. Tim Chester, Good News to the Poor: Social Involvement and the Gospel (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013).

[32] Jonathan Leeman, “Do Evangelicals Need a Better Gospel?,” The Gospel Coalition, 21 December 2017, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/inseparable-asymmetry-gospel/. Cf. D. A. Carson, “Editorial,” Them 33.2 (2008): 1–3; D. A. Carson, “How Do We Work for Justice and Not Undermine Evangelism?,” The Gospel Coalition, 18 October 2010, http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2010/10/18/asks-carson-justice-evangelism/; D. A. Carson, “The Hole in the Gospel,” Them 38 (2013): 353–56.

Jonathan Leeman and Andrew David Naselli

Jonathan Leeman is editorial director for 9Marks in Washington, D.C., a pastor of Cheverly Baptist Church, and author of several books, including Political Church: The Local Assembly as Embassy of Christ’s Rule and How the Nations Rage: Rethinking Faith and Politics for a Divided Age.

Andy Naselli is associate professor of systematic theology and New Testament for Bethlehem College & Seminary in Minneapolis, a pastor of Bethlehem Baptist Church, administrator of Themelios, and author of several books, including Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ (coauthored with J. D. Crowley).

Other Articles in this Issue

This article is a brief response to Bill Mounce’s recent Themelios essay in which he argues that functional equivalence translations such as the NIV are the most effective approach to Bible translation as they carry over the meaning of the original text...

In 1 Timothy 2:15, Paul asserts “the woman will be saved through the childbirth...

This article argues that Paul compares the day of the Lord to a thief in the night in 1 Thessalonians 5:2 because of the influence of Joel 2:9...

The Jerusalem Donation was the Apostle Paul’s largest charity drive...