Volume 19 - Issue 1

Science and faith: boa constrictors and warthogs?

By Steve BishopIntroduction

The relationship between science and religion, and notably Christianity, is a perennial subject. It has been likened by Ted Peters (cited in Barbour 1990 p. 4) to a fight between a boa constrictor and a warthog: the victor swallows the loser. Many have claimed that science has swallowed Christianity:

Between science and religion there has been a prolonged conflict, in which, until the last few years, science has invariably proved victorious. (Russell 1935 p. 7)

The conflict metaphor, which had its origin in the writings of John Draper (1875), became more popular through Andrew Dickson White (1896). The main thesis of White’s and Draper’s work was based on misinformation and half-truths, and many scholars have exposed the naïvety of the conflict category (e.g.Lindberg and Numbers 1986 and Russell 1989). Nevertheless, the conflict metaphor is still prevalent. It provides a pertinent example of how worldview colours perception of reality (Caudill 1985). The combatants in the conflicts that did exist were not science and Christianity:

much of the conflict between science and religion turns out to have been between new science and the sanctified science of the previous generation. (Brooke 1991 p. 37)

Science and religion are not like boa constrictor and warthog. They are not in conflict—as a discussion of miracles will show. Neither are they totally independent. The fallacious view of science as objective and value-free, and faith as subjective and value-laden, has long been demolished by philosophers of science. Unfortunately, these views are still propounded by the popular media. Faith is integral to the scientific enterprise. If this is so, then a distinctively Christian view of science is possible.

A biblical perspective on science

If conflict is an inadequate way to describe the relationship between Christianity and science, what then is the relationship? In an attempt to answer this question we shall begin with a brief biblical overview. To do so I will utilize the creation, fall, redemption motif.

Creation

God, through Christ, is the source and sustainer of all things. Therefore, science has its roots in God. The command to humanity as the image-bearers of God is to subdue and rule the creation. This is not to be seen in terms of domination, but rather as a shepherd may look after her sheep or a gardener her garden (e.g.Houston 1979). It is an injunction to develop and fill the creation, to continue the creative work of God. Hence it is here we find the biblical basis for science: it is part of our calling to care for and open up God’s good creation, to develop culture. Adam’s naming of the animals can perhaps be seen in this context as one of the first scientific tasks, that of observation and classification.

Science, then, is a God-given cultural activity which is to be done in dependence on God and his Holy Spirit. It is not an autonomous activity, it is not a body of knowledge independent of God.

Fall

However, then came sin. This decisive event is well described by Walther Eichrodt:

This event has the character of a ‘Fall’, that is, of a falling out of the line of the development willed by God. (Eichrodt 1972 p. 406)

No area of life is untainted by sin. Consequently all relationships are broken: humanity and God, humanity and the earth, humanity and humanity, male and female, humanity and the animals, animals and animals.… Aspects of God’s creation are given elevated roles they were not intended to have. This is exemplified in fallen 20th-century humanity’s approach to science, technology and economics. They have become the unholy trinity of scientism, technicism and economicism. They have become idols, the gods of our age.1 They are worshipped in place of, or in some cases as well as, God.

Science claims to be omnicompetent. The only way to reliable knowledge is through science. This is the view of no less a person than Bertrand Russell:

Whatever knowledge is attainable, must be obtained by scientific methods; and what science cannot discover, mankind cannot know. (Russell 1935 p. 243)

and, more recently, the biologist Richard Dawkins:

In the art of evaluating evidence, science comes into its own. The correct method for evaluating evidence is the scientific method. If a better one emerged, science would embrace it. (Dawkins 1992 p. 3)

Science subsumes every aspect of life: we have the science of beauty therapy, the science of catering, the science of food and cooking, the science of hairdressing,2 … etc. Even ethical issues will be replaced by science; according to the biologist Edward Wilson in his book Sociobiology:

The time has come for ethics to be moved temporarily from the hands of the philosophers and biologicized. (cited in Midgley 1992 p. 261)

Wilson’s reply to God’s questions to Job (Job 38–39) are revealing:

Yes, we do know and we have told. Jehovah’s challenges have been met and scientists have pressed on to solve even greater puzzles. The physical basis of life is known; we understand approximately how and when it started on earth. New species have been created in the laboratory.…

Salvation comes through science. Even Francis Bacon saw science as undoing the effects of the fall.

The other extreme is that science is the scapegoat for almost all the ills of the world. Lynn White, Jr (1967) placed the blame for the ‘ecologic crisis’ on science and Christianity.3 Many examples illustrate the problems scientific advances confront us with: Hiroshima, Bhopal, Love Canal, Chernobyl. The fall has distorted the God-given role and function of science: consequently, it has become both deified and demonized by different parties.

Redemption

As sin has affected every area and aspect of life, so too does redemption. Redemption potentially ‘undoes’ the fall. Redemption means that science can be restored to its right place. It should neither be divinized nor denigrated. It has an important, albeit limited, role to play in developing the creation. Redeemed humanity can now transform the scientific enterprise and redirect it so that it can be used wisely and responsibly under God to open up and develop the creation. One step to restoring science to its God-given role is to expose the false claim that science is neutral.

The myth of neutrality

It is often assumed that science is an objective, value-free activity. This myth has been promulgated by the school of philosophy known as positivism; it has in part been responsible for the elevation of science above religion. Positivism, founded by Auguste Comte (1798–1857), is the position that all knowledge is based on the senses, so we can only know through observation and experiment. More recent and more radical advocates of positivism were the Vienna Circle, and those named the logical positivists. The late Alfred Ayer (1910–89) was a logical positivist; his ‘bestseller’, Language, Truth and Logic, popularized this philosophy in the UK. Logical positivists maintain that experience is the source of knowledge. Mary Midgley makes this pertinent observation:

They [scientists] moved gradually from the traditional Comtian Positivism, which claimed to bring spiritual matters under the dominion of science, to logical-positivist positions which put such matters outside the province altogether. The resulting muddled metaphysic still underlies many of our problems today. (Midgley 1992 p. 45)

Science, however, is subjective and value-laden. It is not neutral. This point is poignantly made by an Alternative Nobel Prize winner:

There is now a growing realisation that science has embodied within it many of the ideological assumptions of the society which has given rise to it. (Cooley 1987 pp. 90–91)

To the scientists and technologists who view their work as neutral, he has this warning:

… they are dangerously mistaken in regarding their work as being neutral. Such a naive view was ruthlessly exploited in the Third Reich as Albert Speer pointed out in his book Inside the Third Reich: ‘Basically, I exploited the phenomenon of the technician’s often blind devotion to his task. Because of what appeared to be the moral neutrality of technology, these people were without any scruples about their activities.’ (Cooley 1987 p. 176)

Science has both an intrinsic and an extrinsic ‘non-neutrality’.

Extrinsic values

These are the sociological factors which negate any claim to neutrality. Science is not done in a social, economic, political or cultural vacuum. Leslie Stevenson makes a salient point:

[The scientist] will now have to recognize that the funds for his research will probably be given with a fairly close eye to possible applications, be they military, industrial, medical, or whatever. Such research cannot be said to be value-free. (1989 p. 216)

Intrinsic values

Philosophical factors also reveal neutrality to be a myth. The most obvious of these is the fact/value dualism promulgated by the positivists. Much debate about science presupposes a distinction between facts and values. Facts are objective and public, values are subjective and personal. This distinction is a fallacy. Facts are value-laden and are often determined by culture: for Kepler, it was a fact that the earth goes round the sun, and yet for Tycho Brahe, it was a fact that the sun goes around the earth! Our observations are theory-dependent. We see what we want to see. Our worldview affects all that we do. Every human activity is bound to a worldview: science is no exception. Any claims to neutrality are hollow. This is also the testimony of more recent advances in the philosophy of science. It is to a brief and inevitably oversimplified overview of the philosophy of science that we now turn.

A brief philosophy of science

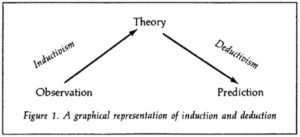

The major school of philosophy that has dominated the philosophy of science in the past is inductivism. Inductivism is the scientific method that moves from a series of observations to a hypothesis; from the specific (this block of ice melts at 0ºC) to the general (all ice melts at 0ºC). This view of science has long been discarded by philosophers of science, yet many school teachers of science still hold an inductivist view of science (Hodson 1986).

The death-blow to inductivism is the recognition that observation is not neutral. Observation is theory-dependent; it is therefore impossible to be a neutral observer. What we ‘see’ will depend on what we know and what we expect to see. Any number of optical illusions illustrate this point.

If observation is theory dependent then it follows that observation will be governed by any pre-existing theory: sugar in a liquid dissolves; we no longer see it disappear (Hodson 1986 p. 218)! In a similar vein, N.R. Hanson asks, ‘Do Kepler and Tycho Brahe see the same thing in the east at dawn?’ (Hanson 1958 p. 5).

Deductivism is a close relative of inductivism. Instead of moving from the specific (events) to the general (laws, theories), deductivism starts with a law or theory and deduces another event. If the event deduced does not occur then the law or theory may require some modification.

Both inductivism and deductivism assume the neutrality and autonomy of science. They assume that there is a universal scientific method. Recent philosophical developments have undermined both these assumptions and have placed more emphasis on the social context of science. They have even gone as far as denying the existence of any method that could be called scientific. These developments are associated with Popper, Kuhn, Feyerabend and Polanyi, whose ideas we will examine briefly.

Sir Karl R. Popper (1902–)

One of Popper’s concerns was to demarcate science from pseudoscience. He rejected the positivist idea that verification was decisive; for Popper, scientific theories could not be proved, they could only be falsified. Science could not represent a body of objective truths, it was merely statements, laws and theories that so far had not been disproved.

Rejecting an ínductive view of science, Popper advocated hypothetico-deductivism. Deductions are made on the basis of an hypothesis. If the deductions can be shown to be false then the hypothesis must be rejected or at best modified. Imre Lakatos (1922–73) developed and modified this approach (Lakatos 1970).

Thomas S. Kuhn (b. 1922)

Originally trained as a theoretical physicist, Kuhn wrote his major work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions4after being exposed to a history of science course; he describes the book as ‘an attempt to explain to myself and friends how I happened to be drawn from science to its history in the first place’ (p. vii). Kuhn rejects the popular view of science as ‘development-by-accumulation’ (p. 2), a view popularized in standard histories of science. He introduced the concept of paradigm shifts to explain how he saw the development of science.

For Kuhn, three phases take place in the development of science: normal science, crisis and revolutionary science. Normal science is what the majority of scientists do. He calls it ‘puzzle solving’ (p. 30). It provides an ‘articulation’ of the dominant paradigm. Occasionally in the history of science we have been confronted by crises, where the dominant paradigm does not explain certain phenomena. At this point several competing theories vie for dominance: this is the revolutionary phase. Eventually, one of these competing theories will become more widely accepted than the others, and consequently it takes over as the dominant paradigm: revolutionary science becomes normal science and we have come full circle.

Kuhn places much emphasis on the role of paradigms, and rightly so. This emphasis serves once more to show that science is value-(or theory-) laden. Paradigms, or worldviews, shape all our thinking. These paradigms are social in nature, they are communally held and communally determined by the scientific community.

The weakness of Kuhn’s position is that science is condemned to a ‘perpetual revolution’ (Hacking 1983). This is because Kuhn is a relativist: ‘truth’ is determined by the dominant paradigm. Kuhn overemphasizes the social dimension of science and consequently distorts reality. Science is reduced to a social dimension.

Lakatos, criticizing Kuhn’s view, claims that for Kuhn ‘scientific change is a kind of religious change’ (Lakatos 1970 p. 93). It could be said that the philosophy of science is at present undergoing a Kuhnian revolution; certainly Kuhn’s work has caused a paradigm shift to occur in the philosophy of science.

The difference between Popper (and the positivists) and Kuhn can be seen by how they would respond to the following questions about science: 1. Is it an exemplar of rationality? 2. Is there a distinction between observation and theory? 3. Is it cumulative? 4. Does it have a tight deductive structure? 5. Are scientific concepts precise? 6. Is there a methodological unity of science? 7. Can the context of justification be separated from that of discovery? 8. Is science outside time and history? For Popper, the answers to all questions is ‘yes’; for Kuhn, ‘no’ to all questions except the first (Hacking 1983).

Paul Feyerabend (b. 1924)

Feyerabend maintains that there is no such thing as the scientific method; rather, ‘anything goes’! His is an anarchistic view of the scientific method. One of the strengths of Feyerabend is that he debunks the superiority of science over other realms of knowledge. We cannot reject other types of knowledge because they do not conform to the ‘scientific method’, a method that for Feyerabend does not exist (Feyerabend 1975).5

Michael Polanyi (1891–1976)

The Hungarian-born scientist-turned-philosopher, Polanyi, claims that knowledge has what he calls a ‘tacit dimension’: it is personal in nature. ‘We can know more than we can tell’ (Polanyi 1966 p. 4) perhaps best describes his thesis.

Polanyi has made an important contribution to both the philosophy of science and epistemology, a contribution that has important insights for Christians. Unfortunately, his work is little known among Christians. This is not helped by the fact that Polanyi’s work is difficult, primarily because of his ‘breadth of knowledge’ and because he ‘is advocating a U-turn in accepted ways of thinking’ (Scott 1989).6 The work of Lesslie Newbigin’s ‘Gospel and culture’ programme may remedy this neglect of Polanyi. Polanyi has influenced much of Newbigin’s thought (see e.g. Newbigin 1986; 1990; Scott 1992).

Polanyi expounds what he describes as a ‘post-critical philosophy’, in the spirit of Augustine (1958 p. 266):

We must now recognize belief once more as the source of all knowledge. Tacit assent and intellectual passions, the sharing of an idiom and of a cultural heritage, affiliation to a like-minded community: such are the impulses which shape our vision of the nature of things on which we rely for our mastery of things. No intelligence, however critical or original, can operate outside such a fiduciary network. (1958 p. 266)

Several factors are integral to knowledge for Polanyi; these include: a tacit dimension, passion, a network of beliefs, and commitment. All are interconnected. Commitment can be seen as a network of beliefs and this network has a tacit dimension. It is difficult to tie Polanyi down at times because he does not provide a systematic exposition, rather many illustrations and examples.

Passion. The positivists denied any personal, subjective aspect to science; Popper acknowledges it but marginalizes it; Polanyi makes it fundamental to knowledge. This is clearly seen in the role of passion in knowledge:

… scientific passions are no mere psychological by-product, but have a logical function which contributes an indispensable element to science. (1958 p. 134)

The personal participation of the knower in the knowledge he believes himself to possess takes place within a flow of passion. We recognise intellectual beauty as a guide to discovery and as a mark of truth. (1958 p. 300)

The tacit dimension. Riding a bike, recognizing a face in a crowd, swimming, the mastery of tools, are all complex skills. Yet we are not always able to articulate or analyse what we know: ‘we can know more than we can tell’. Knowledge of these skills, or indeed anything, involves two parts—one implicit, the other explicit; these, Polanyi called the subsidiary (or proximal) and the focal (or distal) aspects respectively. Both are mutually exclusive and irreducible (1958 p. 56). In the process of knowing we attend from the subsidiary to the focal. The subsidiary is what we know, but we are not always aware that we know. It is this important aspect of knowing that makes all knowledge personal:

… into every act of knowing there enters a passionate contribution of the person knowing what is being known, … this coefficient is no mere imperfection but a vital component of his knowledge. (1958 p. viii)

This undermines the whole notion of objectivity and neutrality of science. It destroys the whole positivist programme.

A network of beliefs. Knowledge, as well as being personal, also functions within a network of beliefs. This network is not merely about bringing pattern and order to knowledge; it also acts as a vision of reality which filters the sense data before they become observations. This vision of reality provides a framework of ultimate beliefs for knowledge. These beliefs are accepted a-critically on the basis of commitment: they are irrefutable and unprovable.

The scientific enterprise relies upon this tacit framework of beliefs. Hence, Polanyi has shown that faith, not doubt (as Popper held) is a vital aspect of science:

The scientist’s conviction that science works is no better, so far, than the astronomer’s belief in horoscopes or the fundamentalist’s belief in the letter of the Bible. A belief always works in the eyes of the believer (1946 p. 47).

Among these beliefs is: ‘the belief that there is something there to be understood’ (1946 p. 30). He goes on to say:

Thus to accord validity to science—or to any other of the great domains of the mind—is to express a faith which can be upheld only within a community. We realize here the connexion between Science, Faith and Society adumbrated in these essays (Polanyi 1946 p. 59).

Commitment is another important aspect. It has two poles: a personal and an external, universal pole. It is this latter pole that prevents Polanyi’s epistemology from slipping into subjectivism (1958 p. 65). Knowledge cannot be divorced from personal commitment:

Science is a system of beliefs to which we are committed. Such a system cannot be accounted for either from experience as seen within a different system, or by reason without any experience. Yet this does not signify that we are free to take it or leave it, but simply reflects the fact that it is a system of beliefs to which we are committed and which cannot be represented in non-commital terms. (1958 p. 171)

Along with Kuhn, he sees a vital role for the scientific community in the scientific enterprise. Science progresses through faith in the accepted views; it is these views that are determined by the scientific community.

Polanyi’s work thus provides us with important insights: science and faith are not two independent realms, but are both aspects of the same reality; faith informs and shapes science; and the personal is not divorced from science.

Realism versus relativism

One of the major debates in the philosophy of science over the last decade is the realist versus antirealist/relativist controversy. It was in essence this that characterized the difference in approach between Popper and Kuhn. Kuhn claimed that ‘Sir Karl’s view of science and my own are very nearly identical’ (Kuhn 1970 p. 1). Popper’s response is to reject Kuhn’s relativism. He sees relativism as being unable to stand up to criticism.

For the Christian, science is a God-given corporate human activity whereby we explore and investigate God’s good creation in an attempt to understand its order and structure. By its very nature as a human activity, its results and conclusions can only be tentative, fallible and provisional; hence a naïve realist view of science is untenable. This is the ‘naïve’ idea that scientific laws and theories provide an accurate literal description of an objective world. For the naive literalist there is a one-to-one correspondence between theory and reality. Likewise, a relativist position is flawed because we are dealing with a God-given reality which is not the product of social agreement (pace Kuhn).

The theoretical physicist Paul Davies has made this revealing statement:

Few scientists would be willing to suppose that the laws of physics are merely human inventions. To be sure they are formulated by humans, but the physicist is motivated by the belief that the laws of physics reflect some aspects of reality. Without this connection with reality, science is reduced to a meaningless charade. (Davies 1988 p. 59; my emphasis)

Relativism undermines the very basis of scientific investigation. It denies that there is an objective reality to investigate. I would therefore want to suggest that a critical realist view of science is more appropriate for a Christian: that is, that science provides us with a fallible description of the external world. This is the position advocated by many writers, including Arthur Peacocke (1979), Ian Barbour (1966), Stanley Jaki and John Polkinghorne. Jaki claims that the major lesson of the history of science is that scientists ‘cannot live without a realist notion of the universe as the totality of all interacting things’ (1978 p. 276). For Polkinghorne, ‘The realist view … is the only one adequate to scientific experience, carefully considered’. But he goes on to say: ‘If realism is to prove defensible it has to be critical, rather than a naïve, realism’ (1986 p. 22).

Our knowledge of the world is fallible and imperfect. This inevitably means that we have to propose tentative and provisional models and explanations that only represent what we know at present of reality. This does not deny that there is any ‘real world’ ‘out there’. If we have no access to the real world, then science becomes a farce. How can we collect data? There is nothing by which we can judge the truthfulness of our hypotheses, theories or laws. It denies any God-given order to creation; and ultimately it denies the God who is faithful to his creation.

Not all Christians, however, advocate critical realism. Reformed philosopher Gordon H. Clark adopts an instrumentalist view (i.e., theories are useful tools, but not necessarily true). James Moreland advocates an ‘eclectic approach to science that adopts a realist/antirealist view on a case-by-case basis’ (1989 p. 203). I find his reasons for eclecticism could be fulfilled if one adopts a critical realist approach.

Science as a faith activity

During the Holy Week of 1992, instead of the usual ‘religious’ programmes the BBC showed a series of programmes called ‘Soul’,7 which dealt with the way science has paved the way for a more mystical approach to life. Perhaps in future Holy Weeks we will be given a regular diet of science programmes instead of the usual re-run of Jesus? Science has become the new religion, it seems.

Polanyi has shown that faith is integral to scientific investigation: science is an inherently religious activity. Professor Coulson has commented:

Science itself must be a religious activity: ‘a fit subject for a Sabbath day’s study’, as John Ray put it in the seventeenth century. (Coulson 1971 p. 44)

We have already mentioned that science is a human activity and scientific work is inevitably shaped by the scientist’s worldview. A worldview, by definition, rests on certain ultimate questions, such as ‘What is reality?’ and ‘What does it mean to be human?’. The answers to these questions cannot be empirically tested: they are the product of faith. Hence, scientific activity is inherently religious.

We can express this line of argument as follows:

- We all have a worldview.

- A worldview is a product of faith, shaped by religious commitments.

- All human activity is shaped by worldviews.

- Science as a human activity is therefore religious.

The religious nature of science is shown in the beliefs that are necessary for the scientific enterprise. These include the following:

Belief in a material world. If the material world is a mere illusion then scientific activity is foolish.

Belief that the world is orderly. Thomas Torrance makes an insightful remark:

Belief in order, the conviction that, whatever may appear to the contrary in so-called random or chance events, reality is intrinsically orderly, constitutes one of the ultimate controlling factors in all rational and scientific activity. (Torrance 1985 p. 16)

The question remains for the scientist, where does this order come from?

Belief that understanding the world is a valuable exercise. If it were not so, what would be the point of science?

Belief that the world and its order can be known. If it cannot be known then scientific activity would be impossible!

Belief in the trustworthiness of other scientific work. If the scientist did not have faith in colleagues’ results published in the scientific journals then most of his/her time would be spent confirming all the previous work, leaving no time for any fresh research that builds on previous work. This does not imply that all that is published is accurate!

The five beliefs above are necessary for the scientific enterprise; they are also, with the exception of the last one, integral to a Christian worldview. It is therefore no accident that a Christian worldview was necessary for the birth and development of modern science.

The birth of science

The major contribution of the Hungarian-born theologian and Benedictine priest, Stanley Jaki, to the history and philosophy of science has been to show that it was, and could only have been, Christianity that provided the right atmosphere and conditions for science to flourish.

The birth of science came only when the seeds of science were planted in a soil which Christian faith in God made receptive to natural theology and to the epistemology implied in it. (Jaki 1978 p. 160)

It was the philosopher M. B. Foster (1934), in a seminal paper, who showed the debt that the origins and the nature of science owed to Christian theology. The historian R. Hooykaas (1972) likewise came to similar conclusions. Hooykaas sees science as ‘more a consequence than a cause of a certain religious [i.e. Judaeo-Christian] view’, and that the ‘vitamins and hormones’ of science were biblical. Torrance has shown that natural science is based on ‘three masterful ideas’ (Torrance 1980 p. 52) developed by the early church:

(i) The rational unity of the universe: the source of order is God.

(ii) The contingent, i.e. neither necessary nor eternal, rationality or intelligibility of the universe. This is a consequence of God’s creation ex nihilo, which included both space and time.

(iii) The freedom of the universe. A freedom which is contingent provides a release from the ‘tyranny of Determinism’. This freedom is not the product of randomness or chance but is the freedom ‘of the God of infinite love and truth upon which it rests and by which it is maintained’ (Torrance 1980 pp. 58–59). It is these Christian beliefs that made Christianity so influential in the development of science.

It was the rule rather than the exception, historically, that the ‘founding fathers’ of science had Christian commitments (e.g. Russell 1985, 1987). And today there has been no shortage of scientists who stand up and claim to be Christians (cf. Berry 1991, Mott 1991).

If Christian beliefs about the nature of reality were the presuppositions vital for the development of science, why is it that the Christian belief in miracles has often proved a stumbling block for those who try to integrate science and faith? How is belief in an orderly world to be reconciled with the claim that miracles happen?

Law, scientific law and miracles

Has science replaced the need to resort to supernatural explanations of miracles? Does God violate his own laws to produce a miraculous event?

In an attempt to unravel some of these knotty questions, we start by examining what is meant by law. ‘Law’ is one of those Humpty Dumpty words—it can mean whatever we want it to mean. It has a wide range of semantic meaning, dependent partly on what ‘language game’ is being played. We need to make a distinction between the way scientists and theologians use the term law.

Scientists and philosophers of science are not agreed on its meaning. One view is that laws are human constructs imposed on reality: they are inventions. At the other extreme is the view that laws are inherent in reality: hence, they are discovered. A middle view, which is the one I take, is that laws are human representations of a God-given reality; they are constantly in need of modification to better represent reality, and at best they will assymptotically approach reality.

Likewise, there is no precision to the meaning of the word ‘law’ in Scripture.

Al Wolters makes some important observations:

[Law] is both compelling (laws of nature) and appealing (norms), and the range of its validity can be both sweeping (general) and individual (particular). (Wolters 1986 p. 17)

Scripture is unequivocal: God orders his creation, both human and non-human, through his decrees and laws (Ps. 147:15–20). Scientific ‘laws’ are human constructions, although they are bound to the creation order. Their usefulness is dependent upon how close they come to the laws by which God orders his creation. They are not, as Kant maintained, human constructions imposed on reality.

‘Miracle’, like ‘law’, is a slippery concept.8 The popular conception of a miracle is threefold: it is a violation of a natural law, it is a divine intervention and it is a supernatural event. All are inadequate.

Swinburne, Mackie and Hume all define miracle as a violation or transgression (Hume) of a law of nature. This notion is a leftover from the 18th century when deism was at its peak. Eichrodt points out that it certainly would not

occur to the devout Old Testament believer to make a breach of the Laws of Nature a condicio sine qua non of the miraculous character of an event. (p. 163)9

God does not violate his own laws, but works with and through them; he is faithful to the creation order, which had its origin in him. This is not to say that God is subject to his laws. Perhaps Augustine was near to the truth when he described a portent (miracle) as an event that ‘happens not contrary to nature, but contrary to what we know as nature’ (De Civitate Dei XII.8). Fuller objects to such a definition because it may mean, scientific advances permitting, that ‘we shall know so much about nature that there will be no place for miracle after all’ (1963 p. 8). The objection is ill-founded.

It is likewise a mistake to describe miracles as divine interventions. An intervention implies that the intervener is absent prior to the intervention. God is present in all of creation, it is therefore illogical to describe his action in the creation as an intervention (Davies 1992).

Can we describe miracles as a supernatural phenomenon? The idea that miracles are supernatural events has its origin in rationalism, not in the scriptures. God is the God of the laws of nature: he does not violate his own principles to work a miracle. Miracles are natural events.10 Eichrodt, again, points out that ‘even the course of Nature itself counts as a miracle’ (p. 162). Nature is not autonomous: all things are held together by Christ. He is both the source and sustainer of all things. Fallen nature is not normal, as rationalism assumes, and supernaturalism, with its nature/supernature dualism, need not be invoked to explain that which rationalism cannot. As Diemer puts it:

The fundamental fault of supernaturalism is that it begins with a rationalistic and deistic theory of nature in which only a nature torn loose from its moorings and impoverished is reckoned with.… As long as rationalism exists, supernaturalism will not disappear. Supernaturalism fills the vacuum that rationalism creates. (Diemer nd p. 17)

How then are we to explain miracles? John Polkinghorne suggests that the fundamental problem of miracles is

how these strange events can be set within a consistent overall pattern of God’s reliable activity; how can we accept them without subscribing to a capricious interventionist God, who is a concept of paganism rather than Christianity. (Polkinghorne 1989 p. 51)

To this we might add: ‘and without subscribing to an unbiblical supernaturalism’.

Miracles are part of the created order. In performing miraculous events, Jesus was restoring the creation to its original order. They are glimpses of the consummated kingdom of God, signposts to the kingdom, or, as Polkinghorne has it, ‘transparent moments in which the Kingdom is found to be manifestly present’; they are restoring humans and the creation to their proper relationships.

Aspects of the fall are temporarily halted: sickness and death are robbed of their dominion. The ultimate example, of course, is of Jesus’ resurrection: he is the firstfruits of what it will be to have a transformed resurrection body; we like him will be raised to immortality.

This means that scientific descriptions of miracles are permissible but they are not the whole truth. They may be able to explain them in certain cases, but as has often been said, ‘explanation is not explaining away’. Hence, contra Fuller, scientific explanations will not mean that there will be no place for miracles.

Conclusion

I am all too aware that much ground has been covered in this far too cursory overview, and that far too many questions will have been raised rather than answered—but that is not such a bad thing. It would be presumptuous, therefore, to offer any conclusions. And any conclusions, like the scientific enterprise, can only be tentative, fallible, corrigible and value-laden. Suffice to say that science is a God-ordained corporate human activity, and like all truth can never be in conflict with him who is the Truth.

Neither are science and faith two separate, independent, distinct realms: both are engaged in a search for truth, both have their source and origin in God, and ultimately, science is rooted in faith commitments. Faith is integral to the scientific enterprise.

The prophet Isaiah paints a picture of the lion and the lamb lying down together in harmony on the new earth. Perhaps too we will see the boa constrictor and warthog coexisting in peace.

Bibliography

R.T. Allen 1978, ‘The philosophy of Michael Polanyi and its significance for education’, Journal of Philosophical Education, Vol. 12, pp. 167–177.

Ian G. Barbour 1966, Issues in Science and Religion (London: SCM).

——— 1990, Religion in an Age of Science (Gifford Lectures 1989–1991) (London: SCM), Vol. 1.

R.J. Berry (ed.) 1991, Real Science, Real Faith (Leicester: IVP).

Steve Bishop 1991, ‘Green theology and deep ecology: New Age or new creation?’, Themelios Vol. 16. 3 (April/May 1991), pp. 8–14.

Ian Bradley 1990, God is Green: Christianity and the Environment (London: DLT).

Richard Bauckham (forthcoming), ‘Attitudes to the non-human creation in the history of Christian thought’, in Stewarding Creation, ed. Steve Bishop (Bristol: Regius Press).

John Hedley Brooke, Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

David S. Caudill 1985, ‘Law and worldview: problems in the creation-science controversy’, Law and ReligionVol. 3 (1), pp. 1–46.

A.F. Chalmers 1982 (2nd edn), What is This Thing Called Science? (Milton Keynes: Open University Press).

Mike Cooley, Architect or Bee? The Human Price of Technology (London: The Hogarth Press, 1987; original version, Langley Technical Services, 1980).

C.A. Coulson 1971, Science and Christian Belief (London: Fontana (2nd edn)). Originally published by Oxford University Press in 1955.

Brian Davies OP 1992, ‘Miracles’, New Blackfriars Vol. 73, No. 857 (February), pp. 102–120.

Paul Davies 1988, ‘Law and order in the universe’, New Scientist (15 October).

Richard Dawkins 1992, ‘The culture of science’, The Observer Schools Report (2 February).

J.H. Diemer no date, ‘Miracles happen: toward a biblical view of nature’ (Toronto: ICS).

——— 1977, Nature and Miracle (Toronto: Wedge Publishing Foundation).

John Draper 1875, History of Conflict between Religion and Science (London: International Scientific Series).

Walther Eichrodt 1972, Theology of the Old Testament Vol. 2 (London: SCM).

M.B. Foster 1934, ‘The Christian doctrine of creation and the rise of modern natural science’, Mind Vol. 43, pp. 446–468; also reprinted in C.A. Russell (ed.), Science and Religious Belief: A Selection of Recent Historical Studies (London: University of London Press/Open University Press, 1973).

Paul Feyerabend 1975, Against Method (London: New Left Books).

R.H. Fuller 1963, Interpreting the Miracles (London: SCM).

Bob Goudzwaard 1984, Idols of Our Time (Leicester: IVP).

Marjorie Grene (ed.) 1960, Knowing and Being: Essays by Michael Polanyi (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

Ian Hacking 1983, Representing and Intervening: Introductory Topics in the Philosophy of Natural Science(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

N.R. Hanson 1958, Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Hodson 1986, ‘Philosophy of science and science education’, Journal of Philosophy of Education Vol. 20, pp. 215–225.

- Hooykaas 1972, Religion and the Rise of Modern Science (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press).

Walter J. Houston 1979, ‘ “And let them have dominion.…” Biblical views of man in relation to the environmental crisis’, Studia Biblica I (1978) (Sheffield: JSOT Press), pp. 161–184.

Stanley Jaki 1978, The Road to Science and the Ways to God (The Gifford Lectures 1974–5 and 1975–6) (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press).

Thomas S. Kuhn 1986, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (New York: New American Library).

——— 1970, ‘Logic of discovery or psychology of research’, in Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, ed. Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Imre Lakatos 1970, ‘Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes’, in ibid.

David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers 1986, ‘Beyond War and peace: a reappraisal of the encounter between Christianity and science’, Church History Vol. 55, pp. 338–354.

J.P. Moreland 1989, Christianity and the Nature of Science: A Philosophical Investigation (Grand Rapids: Baker).

Mary Midgley 1992, ‘The idea of salvation through science’, New Blackfriars Vol. 73, pp. 257–265.

——— 1992, ‘Strange contest: science versus religion’, in The Gospel and Contemporary Culture, ed. Hugh Montefiore (London: Cassell).

Sir Nevill Mott (ed.) 1991, Can Scientists Believe? Some Examples of the Attitudes of Scientists to Religion(James & James).

Lesslie Newbigin 1986, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture (London: SPCK).

——— 1989, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (London: SPCK).

W.H. Newton-Smith 1981, The Rationality of Science (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

Michael Polanyi 1946, Science, Faith and Society (Riddell Memorial Lectures) (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

——— 1958, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

——— 1966, The Tacit Dimension (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

John Polkinghorne 1986, One World: The Interaction of Science and Theology (London: SPCK).

——— 1989, Science and Providence: God’s Interaction with the World (London: SPCK).

Bertrand Russell 1935, Religion and Science (The Home University Library of Modern Knowledge) (London: Thornton Butterworth).

Colin A. Russell 1987, ‘Some founding fathers of physics’, Physics Education Vol. 27 (1), pp. 27–33.

——— 1990, ‘The conflict metaphor and its social origin’, Science and Christian Belief Vol. 1, pp. 3–23.

Drusilla Scott 1989, Everyman Revived: The Common Sense of Michael Polanyi (Lewes: The Book Guild).

——— 1992, ‘Can religion ever retake its place from science as holder of public truth?’, The Church of England Newspaper, 3 July, p. 9.

Barbara S. Spector 1993, ‘Order out of chaos: restructuring schooling to reflect society’s paradigm shift’, School Science and Mathematics Vol. 93 (1), pp. 9ff.

Leslie Stephenson 1989, ‘Is scientific research value-neutral?’, Inquiry Vol. 32, p. 216.

T.F. Torrance 1980, The Ground and Grammar of Theology (The Richard Lectures for 1978–79) (Virginia: University Press of Virginia).

——— 1985, Christian Frame of Mind (Edinburgh: Handsell Press).

Del Ratzsch 1986, Philosophy of Science: The Natural Sciences in Christian Perspective (Leicester: IVP).

Andrew Dickson White 1896, History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (London: MacMillan).

Lynn White, Jr 1967, ‘The historical roots of our ecologic crisis’, Science Vol. 155 (3767) (March), pp. 1203–1207.

David Wenham and Craig Blomberg 1986, Gospel Perspectives Vol. 6: The Miracles of Jesus (Sheffield: JSOT Press).

Albert Wolters 1986, Creation Regained: A Transforming View of the World (Leicester: IVP).

1 An excellent analysis of contemporary idola try is provided by the Christian economist Bob Goudzwaard 1984.

2 These terms are the titles of books; all are published by Hodder and Stoughton!

3 ‘For a critique of White’s thesis see Bishop 1991 and references therein, especially footnote 2. Other recent critiques of White include Ian Bradley 1990 and Bauckham (forthcoming).

4 Originally published in 1962 by the University of Chicago Press; an enlarged second edition appeared in 1970. The page numbers I cite are taken from a reprint of the second edition (New American Library, 1986).

5 Useful discussions on Feyerabend are to be found in Newton Smith 1981 and Chalmers 1982.

6 Scott’s book (1989) provides an excellent introduction to Polanyi’s main ideas.

7 Presented by Anthony Clare and produced by Angela Tilby, the series was broadcast in the UK on 13, 15 and 16 April 1992.

8 I am not concerned here with the historicity of miracles. On this see, for example, Wenham and Blomberg 1986.

9 However, Eichrodt thinks that some events that do violate the laws are not unknown: he cites Nu. 16:30; Jos. 10:10ff. and 2 Ki. 20:10 as examples.

10 On this and the following discussion see J. H. Diemer no date and 1977.

Steve Bishop

Bristol