Volume 7 - Issue 1

The Interpreted Word: Reflections on Contextual Hermeneutics

By C. René PadillaThe word of God was given to bring the lives of God’s people into conformity with the will of God. Between the written word and its appropriation by believers lies the process of interpretation, or hermeneutics. For each of us, the process of arriving at the meaning of Scripture is not only highly shaped by who we are as individuals but also by various social forces, patterns and ideals of our particular culture and our particular historical situation. (‘Culture’ is used in this paper in a comprehensive way to include not only technical skills, lifestyle, attitudes and values of people, but also their thought patterns, cognitive processes and ways of learning, all of which ultimately express a religious commitment.)

One of the most common approaches to interpretation is what may be called the ‘intuitive’ approach. This approach, with its emphasis on immediate personal application, is found in many of the older commentaries and in contemporary popular preaching and devotional literature.

In contrast to this is the ‘scientific’ approach, which employs the tools of literary criticism, historical and anthropological studies, linguistics, etc. It is adopted by a large majority of biblical scholars, and by Christians interested in serious Bible study. It appreciates the need for understanding the original context. But like the intuitive approach, it may not be sensitive to contemporary social, economic and political factors and cultural forces that affect the interpretive process.

A third approach is the ‘contextual’ approach. Combining the strengths of the intuitive and scientific methods, it recognises both the role of the ancient world in shaping the original text and the role of today’s world in conditioning the way contemporary readers are likely to ‘hear’ and understand the text.

The Word of God originated in a particular historical context—the Hebrew and Graeco-Roman world. Indeed, the Word can be understood and appropriated only as it becomes ‘flesh’ in a specific historical situation with all its particular cultural forms. The challenge of hermeneutics is to transpose the message from its original historical context into the context of present day readers so as to produce the same kind of impact on their lives as it did on the original hearers or readers.

Thus, hermeneutics and the historical context are strongly linked. Without a sufficient awareness of the historical factors, the faith of the hearers of the Gospel will tend to degenerate into a ‘culture-Christianity’ which serves unredeemed cultural forces rather than the living God. The confusion of the Gospel with ‘culture-Christianity’ has been frequent in western-based missionary work and is one of the greatest problems affecting the worldwide church today. The solution can come only through a recognition of the role that the historical context plays in both the understanding and communication of the biblical message.

Traditional hermeneutics

The unspoken assumption of the intuitive model is that the situation of the contemporary reader largely coincides with the situation represented by the original text. The process of interpretation is thought to be rather straightforward and direct (diagram 1).

Diagram 1

This approach brings out three elements essential to sound biblical hermeneutics. First, it clearly assumes that Scripture is meant for ordinary people and is not the domain of trained theologians only. (Was it not the rediscovery of this truth that led the sixteenth century Reformers to translate and circulate the Bible in the vernacular?) Second, it highlights the role of the Holy Spirit in illuminating the meaning of the Scripture for the believer. Third, it emphasises that the purpose of Scripture is not merely to lead readers to an intellectual apprehension of truth but to elicit a conscious submission to the Word of God speaking in Scripture. These elements are of particular importance at a time when, as Robert J. Blaikie protests, ‘Only as mediated through the scholarly priesthood of “Biblical Critics” can ordinary people receive the truth of God’s Word from the Bible.’1

On the other hand, the intuitive approach can easily lead to allegorisations in which the original meaning of the text is lost. Someone has said that allegory is the son of piety. The fantastic interpretations by such reputable theologians as Origen and Augustine, Luther and Calvin, are more or less sophisticated illustrations of a piety-inspired approach to the Bible. The question to be posed to this approach is whether the appropriation of the biblical message is possible without doing violence to the text.

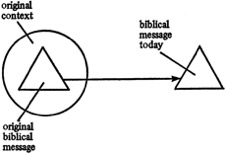

The scientific approach also has its merits and defects. Anyone with even a superficial understanding of the role of history in shaping the biblical revelation will appreciate the importance of linguistic and historical studies for the interpretation of Scripture. The raw material of theology is not abstract, timeless concepts which may be simply lifted out of Scripture, but rather a message embedded in historical events and the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of the biblical authors. One of the basic tasks of interpretation therefore is the construction of a bridge between the modern readers or hearers and the biblical authors by means of the historical method. Thus, the Sitz im Leben (‘life situation’) of the biblical authors can be reconstructed, and the interpreters, by means of grammatico-historical exegesis, can extract those normative (though not exhaustive) and universal elements which the ancient text conveys. This view of the interpretive process is represented in diagram 2.

This approach throws into relief the historical nature of biblical revelation. In a way, it widens the gulf between the Bible and modern readers or hearers. In so doing, however, it witnesses to the fact that the Word of God today has to do with the Word of God which was spoken in ancient times by the prophets and apostles. Unless modern interpreters allow the text to speak out of its original situation, they have no basis for claiming that their message is continuous with the message recorded in Scripture.

The problem with the scientific approach is first, that it assumes that the hermeneutical task can be limited to defining the original meaning of the text, leaving to others its present application. Second, it assumes that the interpreters can achieve an ‘objectivity’ which is neither possible nor desirable. It is not possible, because contemporary interpreters are stamped with the imprint of their particular time and place as surely as is the ancient text, and therefore they inevitably come to the text with historically-conditioned presuppositions that colour their exegesis. It is not desirable, because the Bible can only be properly understood as it is read with a participatory involvement and allowed to speak into one’s own situation. Ultimately, if the text written in the past does not strike home in the present it has not been understood.

Diagram 2

The contextual approach and the hermeneutical circle

How can the chasm between the past and the present be bridged? An answer is found in the contextual approach, which combines insights derived from classical hermeneutics with insights derived from the modern hermeneutical debate.

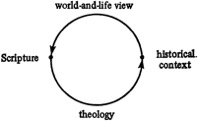

In the contextual approach both the context of the ancient text and the context of the modern reader are given due weight (diagram 3).

Diagram 3

The diagram emphasises the importance of culture to the biblical message, in both its original and contemporary forms. That is, there is no such thing as a biblical message detached from a particular cultural context.

However, contrary to the diagram, the interpretive process is not a simple one-way process. For whenever interpreters approach a particular biblical text they can do so only from their own perspective. This gives rise to a complex, dynamic two-way interpretive process depicted as a ‘hermeneutical circle’, in which interpreters and text are mutually engaged. The dynamic interplay will be seen more clearly if we first examine the four elements of the circle: (1) the interpreters historical situation; (2) the interpreter’s world-and-life view; (3) Scripture; and (4) theology.

- The interpreters historical situation. Interpreters do not live in a vacuum. They live in concrete historical situations, in particular cultures. From their cultures they derive not only their language but also patterns of thought and conduct, methods of learning, emotional reactions, values, interests and goals. If God’s Word is to reach them, it must do so in terms of their own culture or not at all.

This is clear from the Incarnation itself. God did not reveal himself by shouting from heaven but by speaking from within a concrete human situation: he became present as a man amongst men, in Jesus, a first-century Jew! This unmistakably demonstrates God’s intention to make his Word known from within a concrete human situation. No culture as a whole reflects the purpose of God; in all cultures there are elements which conspire against the understanding of God’s Word. If this is recognised, it follows that every interpretation is subject to correction and refinement; there is always a need for safeguards against syncretism, i.e., cultural distortions of the Word of God. Syncretism occurs whenever there is accommodation of the Gospel to premises or values prevalent in the culture which are incongruent with the biblical message.

On the other hand, every culture possesses positive elements, favourable to the understanding of the Gospel. This makes possible a certain approach to Scripture which brings to light certain aspects of the message which in other cultures remain less visible or even hidden. The same cultural differences that hinder intercultural communication turn out to be an asset to the understanding of the many-sided wisdom of God; they serve as channels to aspects of God’s Word which can be best seen from within a particular context.

Thus, the hermeneutical task requires an understanding of the concrete situation as much as an understanding of Scripture. No transposition of the biblical message is possible unless the interpreters are familiar with the frame of reference within which the message is to become meaningful. There is, therefore, a place for auxiliary sciences such as sociology and anthropology which can enable interpreters to define more precisely the horizons of their situation, even as linguistics, literature and history can help them in their study of the text and its original context.

- The interpreter’s world-and-life view. Interpreters tend to approach Scripture from their particular perspectives. They have their own world-and-life view, their own way of apprehending reality. This imposes certain limits but also enables them to see reality as a coherent whole. Whether or not they are conscious of it, this world-and-life view, which is religiously determined, lies behind all their activities and colours their understanding of reality in a definite way. We can extend this observation to biblical hermeneutics and say that every interpretation of the text implies a world-and-life view.

Western theology generally has been unaware of the extent to which it is affected by the materialistic and mechanistic world-and-life view. It is only natural, for instance, that those who accept the modern ‘scientific’ view—which assumes a closed universe where everything can be explained on the basis of natural causes—will have difficulty taking the Bible at face value whenever it points to a spirit-world or to miracles. Western theology, therefore, greatly needs the corrective provided by Scripture in its emphasis on a personal Creator who acts purposefully in and through history; on creation as totally dependent upon God; on man as the ‘image of God’, affected by sin and redemption. Such elements are the substance of the biblical world-and-life view apart from which there can be no proper understanding either of reality or of Scripture. It may well be that what prevents westerners from entering into the ‘strange world of the Bible’ is not its obsolete world-and-life view but their own secularistic and unwarranted assumption with regard to the powers of reason!

- Scripture. Hermeneutics has to do with a dialogue between Scripture and the contemporary historical context. Its purpose is to transpose the biblical message from its original context into a particular twentieth-century situation. Its basic assumption is that the God who spoke in the past and whose Word was recorded in the Bible continues to speak today to all mankind in Scripture.

Although the illumination of the Spirit is indispensable in the interpretive process, from one point of view the Bible must be read ‘like any other book’. This means that the interpreters have to take seriously that they face an ancient text with its own historical horizons. Their task is to let the text speak, whether they agree with it or not, and this demands that they understand what the text meant in its original situation. In James Smart’s words,

‘All interpretation must have as its first step the hearing of the text with exactly the shade of meaning that it had when it was first spoken or written. First the words must be allowed to have the distinctive meaning that their author placed upon them, being read within the context of his other words. Then each word has to be studied in the context of the time in order to determine … what meaning it would have for those to whom it was addressed.… The religious, cultural and social background is of the greatest importance in penetrating through the words to the mind of the author.… The omission of any of these disciplines is a sign of lack of respect not only for the text and its author, but also for the subject matter with which it deals.’2

It has been argued, however, that the approach described in this quotation, known as the grammatico-historical approach, is itself typically western and consequently not binding upon non-western cultures. What are we to say to this?

First, no interpreters, regardless of their culture, are free to make the text say whatever they want it to say. Their task is to let the text speak for itself, and to that end they inevitably have to engage with the horizons of the text via literary context, grammar, history and so on.

Second, western theology has not been characterized by a consistent use of the grammatico-historical approach in order to let the Bible speak. Rather a dogmatic approach has been the dominating factor, by which competing theological systems have muted Scripture. Abstract conceptualization patterned on Greek philosophy have gone hand in hand with allegorizations and typologies. Even sophisticated theologians, losing sight of the historical nature of revelation, have produced capricious literary or homiletical exercises.

Third, some point to the New Testament use of the Old as legitimizing intuitive approaches and minimizing the importance of the grammatico-historical approach. But it can hardly be claimed that the New Testament writers were not interested in the natural sense of Old Testament Scripture. There is little basis for the idea that the New Testament specializes in highly imaginative exegesis, similar to that of rabbinic Judaism. Even in Paul’s case, despite his rabbinic training, there is great restraint in the use of allegory. As James Smart has put it, ‘The removal of all instances of allegory from his (Paul’s) writings would not change the structure of his theology. This surely is the decisive test.’3

The effort to let Scripture speak without imposing on it a ready-made interpretation is a hermeneutical task binding upon all interpreters, whatever their culture. Unless objectivity is set as a goal, the whole interpretive process is condemned to failure from the start.

Objectivity, however, must not be confused with neutrality. To read the Bible ‘like any other book’ is not only to take seriously the literary and historical aspects of Scripture but also to read it from the perspective of faith. Since the Bible was written that God may speak in and through it, it follows that the Bible should be read with an attitude of openness to God’s Word, with a view to conscientious response. The understanding and appropriation of the biblical message are two aspects of an indivisible whole—the comprehension of the Word of God.

- Theology. Theology cannot be reduced to the repitition of doctrinal formulations borrowed from other latitudes. To be valid and appropriate, it must reflect the merging of the horizons of the historical situation and the horizons of the text. It will be relevant to the extent that it is expressed in symbols and thought forms which are part of the culture to which it is addressed, and to the extent that it responds to the questions and concerns which are raised in that context. It will be faithful to the Word of God to the extent that it is based on Scripture and demonstrates the Spirit-given power to accomplish God’s purpose. The same Spirit who inspired Scripture in the past is active today to make it God’s personal Word in a concrete historical situation.

Daniel von Allmen has suggested that the pages of the New Testament itself bear witness to this process, as the early Christians, dispersed by persecution from Palestine, ‘undertook the work of evangelism and tackled the Greeks on their own ground. It was they who, on the one hand, began to adapt into Greek the tradition that gave birth to the Gospels, and who, on the other hand, preached the good news for the first time in Greek’.4 They did not consciously set out to ‘do theology’, but simply to faithfully transcribe the Gospel into pagan contexts. Greek-speaking Christian poets then gave expression to the faith received, not in a systematically worked theology, but by singing the work which God had done for them. According to von Allmen, this is the origin of a number of hymns quoted by the New Testament writers, particularly the one in Philippians 2:6–11. The theologians ensured that this new way of expressing the faith corresponded to apostolic doctrine and showed that all theological statements must be set in relation to the heart of the Christian faith, i.e. the universal lordship of Jesus Christ.

In other words, the driving force in the contextualization of the Gospel in apostolic times was the primitive church’s obedience to God’s call to mission. What is needed today, says von Allmen, is missionaries like the Hellenists, who ‘did not set out with a theological intention’, and poets like the authors of the hymns quoted in the New Testament, who ‘were not deliberately looking for an original expression of their faith’, and theologians like Paul, who did not set out to ‘do theology’. Von Allmen concludes, ‘The only object of research which is allowed, and indeed commended, is the kingdom of God in Jesus Christ (cf Mt. 6:33). And theology, with all other things, will be added unto us.’

I would also add that neither the proclamation of the Gospel nor the worship of God is possible without ‘theology’, however unsystematic and implicit it may be. In other words, the Hellenistic missionaries and poets were also theologians—certainly not dogmaticians, but proclaimers and singers of a living theology through which they expressed the Word of God in a new cultural context. With this qualification, von Allmen’s conclusion stands—the way in which Christianity was communicated in the first century sets the pattern for producing contextualized theology today.

Dynamics of the hermeneutical circle

The aim of the interpretive process is the transformation of the people of God within their concrete situation. Now a change in the situation of the interpreters (including their culture) brings about a change in their comprehension of Scripture, while a change in their comprehension of Scripture in turn reverberates in their situation. Thus, the contextual approach to the interpretation of Scripture involves a dialogue between the historical situation and Scripture, a dialogue in which the interpreters approach Scripture with a particular perspective (their world-and-life view) and approach their situation with a particular comprehension of the Word of God (their theology), as indicated in diagram 4.

Diagram 4

We begin the hermeneutical process by analysing our situation, listening to the questions raised within it. Then we come to Scripture asking, ‘What does God say through Scripture regarding this particular problem?’ The way we formulate our question will depend, of course, on our world-and-life view, that is, the historical situation can only approach Scripture through the current world-and-life view of the interpreters. Lack of a good understanding of the real issues involved will be reflected in inadequate or misdirected questions, and this will hinder our understanding of the relevance of the biblical message to that situation. Scripture does not readily answer questions which are not posed to it. Asking the wrong or peripheral questions will result in a theology focussed on questions no one is asking, while the issues that urgently need biblical direction are ignored.

On the other hand, the better our understanding of the real issues in our context, the better will be the questions which we address to Scripture. This makes possible new readings of Scripture in which the implications of its message for our situation will be more fully uncovered. If it is true that Scripture illuminates life, it is also true that life illuminates Scripture.

As the answers of Scripture come to light, the initial questions which arose in our concrete situation may have to be reformulated to reflect the biblical perspective more adequately. The context of theology, therefore, includes not only answers to specific questions raised by the situation but also questions which the text itself poses to the situation.

The deeper and richer our comprehension of the biblical text, the deeper and richer will be our understanding of the historical context (including the issues that have yet to be faced) and of the meaning of Christian obedience in that particular context. The possibility is thus open for changes in our world-and-life view and consequently for a more adequate understanding and appropriation of the biblical message. For the biblical text, approached from a more congenial world-and-life view, and addressed with deeper and richer questions, will be found to speak more plainly and fully. Our theology, in turn, will be more relevant and responsive to the burning issues which we have to face in our concrete situation.

The contextualization of the Gospel

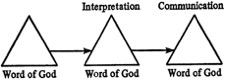

The present situation of the church in many nations provides plenty of evidence to show that all too often the attempt has been made to evangelize without seriously facing the hermeneutical task. Western missionaries have often assumed that their task is simply to extract the message directly from the biblical text and to transmit it to their hearers in the ‘mission field’ with no consideration of the role of the historical context in the whole interpretive process. This follows a simplistic pattern which does not fit reality (diagram 5).

Diagram 5

This simplistic approach to evangelism has frequently gone hand in hand with a western view of Christianity which combines biblical elements with elements of Greek philosophy and of the European-American heritage and places an unbalanced emphasis on the numerical growth of the church. As a result, in many parts of the world Christianity is regarded as an ethnic religion—the white man’s religion. The Gospel has a foreign sound, or no sound at all, in relation to many of the dreams and anxieties, problems and questions, values and customs of people. The Word of God is reduced to a message that touches life only on a tangent.

It would be easy to illustrate the theological dependence of the younger churches on the older churches, which is as real and as damaging as the economic dependence that characterizes the ‘underdeveloped’ countries! An amazing quantity of Christian literature published in these countries consists of translations from English (ranging from ‘eschatology-fiction’ to ‘how-to-enjoy-sex’ manuals) and in a number of theological institutions the curriculum is a photo-copy of the curriculum used at similar institutions in the West.

The urgent need everywhere is for a new reading of the Gospel from within each particular historical situation, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The contextualization of the Gospel can only be the result of a new, open-ended reading of Scripture with a hermeneutic in which Gospel and situation become mutually engaged in a dialogue whose purpose is to place the church under the lordship of Jesus Christ.

It is only as the Word of God becomes ‘flesh’ in the people of God that the Gospel takes shape within history. According to God’s purpose the Gospel is never to be merely a message in words but a message incarnate in his church and, through it, in history. The contextualization of the Gospel demands the contextualization of the church, which is God’s hermeneutical community for the manifestation of Christ’s presence among the nations of the earth.

Correction

In the April 1981 issue of Themelios, we wrongly stated that Anthony Stone is studying for a post graduate degree form the United States. Dr Stone is in fact working with the Theological Research and Communication Institue, New Delhi, India.

1 Secular Christianity and the God Who Acts, Hodder and Stoughton, p. 27.

2 The Interpretation of Scripture, SCM, p. 33.

3 Ibid., p. 30.

4 ‘The Birth of Theology,’ International Review of Mission, January 1975.

C. René Padilla

Born in Ecuador and educated in Colombia, René Padilla now lives in Argentina with his wife Cathy and their five children. He graduated from Wheaton College, USA in Philosophy and Theology. René is now director of Ediciones Certeza, the IFES publishing house in Latin America.