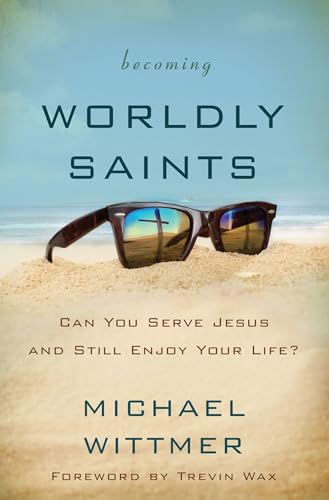

Becoming Worldly Saints: Can You Serve Jesus and Still Enjoy Your Life?

Written by Michael Wittmer Reviewed By Matthew H. PattonI suppose I must be one of the people for whom Wittmer wrote his book. As a recovering ascetic who still wonders whether I am enjoying life too much when I should be living more sacrificially, Wittmer confronts me with the rightful place of enjoyment in the Christian life.

Wittmer is professor of systematic theology at Grand Rapids Theological Seminary, but he writes for the average churchgoer in easy prose and with plenty of chuckles (warning: fans of Cleveland sports teams may find some material offensive!). His central thesis is that “God wants you to enjoy life” (p. 26), and that Christians should not feel false guilt for enjoying God’s good creation. He argues his point by showing how a Christian’s enjoyment of creation fits into the biblical story of creation, fall, and redemption.

Regarding creation, Wittmer emphasizes the goodness of all that God has made. This puts the lie to spiritualism (a.k.a., gnosticism), which says that “matter doesn’t matter.” For Wittmer, separating out parts of our lives as secular or irrelevant to our Christian identity goes directly against the Bible’s teaching. And so, rather than ignoring God’s gifts and focusing exclusively on the Giver, we ought to enjoy creation for what it is.

Wittmer explains the meaning of life in terms of our creational identity: we are to love God, serve others, cultivate the earth, rest every seventh day, and pursue a calling where, in the words of Buechner, our “deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet” (p. 104). All these activities require us to embrace our embodied existence. Wittmer then explains how God’s redemptive purposes in the wake of the Fall do not involve the annihilation of this creation, but rather its restoration. Heaven will be a renewal and perfecting of this earth, where our embodied existence will reach its pinnacle. Taking pleasure in God’s marvelous world continues to be a central expression of our humanity.

Wittmer has a gift for memorable lines, but one sometimes wonders whether people will hear him correctly. For example, “Thank God for the privilege of being human and of being here. Then go have some fun” (p. 67). This could imply that we can pay our respects to God and then go on our merry way, which is not his point in the larger context.

If one takes him in context, Wittmer’s book strikes helpful balances. He does not allow the goodness of all creation to eliminate the biblical priority on our relationship to God: “If God is the source of all value, then everything matters, and those activities that focus most on him matter most of all” (p. 32). Likewise, all wholesome callings are equally good, but being called to church ministry is a “uniquely high” task (p. 105). Wittmer also balances Kuyperian and “two kingdoms” insights, and identifies his own view as fundamentally Kuyperian. He encourages us to live in these tensions, not to escape them.

For this recovering ascetic, much of Wittmer’s book was deeply refreshing. The normal, mundane activities of human existence bring glory to God. God gives good gifts that are to be enjoyed. Loving my neighbor does not mean I need to save the world singlehandedly, or to feel false guilt when I buy a suit while children in Africa are hungry.

And yet something about the book’s overall message does not sit well with Scripture. The call to self-sacrificial suffering is a major part of biblical ethics (Matt. 16:24; Luke 9:57–62; 14:27). The runner straining with all his might to the finish line (1 Cor. 9:24–27) does not come to mind as a way of illustrating how to apply Wittmer’s book. (Instead, maybe we think of lounging on the beach? See the cover.) The Bible speaks with intense urgency about the present time (Eph 5:16), but I fear that all too many American Christians will read Wittmer’s book as an invitation to a lifestyle of complacent hedonism. The balance between these texts and the legitimacy of delighting in creation is hard to strike, and to his credit, Wittmer does not ignore these passages. But the call to take up one’s cross does not seem functional in the book, so that at the end a reader could explain how the pursuit of pleasure in God’s creation fits with the call to “fill what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ” (Col. 1:24; see 2 Cor. 1:5; 1 Pet. 4:13).

Perhaps there is a theological explanation for this imbalance. Wittmer bases his ethic on our identity as humans, not as Christians (p. 70). Hence his explanation of our life calling is based on Genesis 1–2 (loving God, cultivating the earth, etc.). But Paul says that as Christians we are being conformed to the “image of [God’s] Son” (Rom 8:29), and Jesus’s image not only fulfills those creational mandates, but is marked by the narrative of suffering unto glory. Therefore, our present existence is primarily cross-shaped: we do not forego the good things God gives, but our goal is to live out the sacrificial, self-emptying love of our Savior. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it in his book The Cost of Discipleship: “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”

Matthew H. Patton

Matthew H. Patton

Bethel Orthodox Presbyterian Church

Wheaton, Illinois, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

The Eighth Commandment as the Moral Foundation for Property Rights, Human Flourishing, and Careers in Business

by Wayne GrudemThe Eighth Commandment, “You shall not steal,” has massive implications for human life on earth...

Kyle Faircloth argues that Daniel Strange’s earlier work on the question of the unevangelised is undermined by his more recent theology of religions, and in particular his theory of a ‘remnantal’ revelation...

Daniel Strange on the Theological Question of the Unevangelized: A Doctrinal Assessment

by Kyle FairclothAlthough evangelicals agree the church must be fervent in seeking to reach those who have little or no access to the gospel, this missiological consensus has not led to a theological consensus regarding the salvific state of those whom the church never reaches...

John Barclay has written a stimulating and ground-breaking book on Paul’s theology of gift...

The Scribe Who Has Become a Disciple: Identifying and Becoming the Ideal Reader of the Biblical Canon

by Ched SpellmanThe literary notion of “implied reader” invokes a series of hermeneutically significant questions: What is it? Who produces it? and How can it be identified? These questions naturally lead to a further query: What is the relationship between this implied reader of a text and an actual reader of a text? This type of study is often associated primarily with reader-response theory and purely literary approaches...