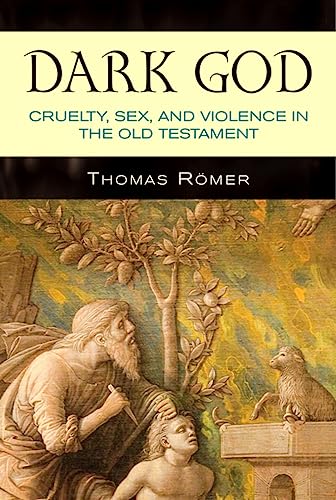

Dark God: Cruelty, Sex, and Violence in the Old Testament

Written by Thomas Römer Reviewed By David T. LambSince Römer’s Dark God was published recently in 2013, it appears to be following a collection of similarly themed books on the subject of the supposedly bad behavior of God in the OT—see works by Eric Seibert (2009), Paul Copan (2011) and myself (2011)—but the French original (Dieu obscur. Cruauté, sexe et violence dans l’Ancien Testament) was actually published four years earlier (2009), and thus he was on the cutting edge of this trend. Römer clearly has a popular audience in mind and his writing (translated into English by Sean O’Neill) is clear and straightforward. Among the four discussions of disturbing divine behavior just mentioned, Römer’s is the shortest (146 pp. plus 8 pp. of notes), and he includes eight relevant black-and-white images of ancient Near Eastern inscriptions or art (pp. 32, 33, 34, 35, 105, 127, 132, 134). After his introduction, Römer’s chapter titles ask whether God is (1) male, (2) cruel, (3) a warlike despot, (4) self-righteous, (5) violent/vengeful and (6) comprehensible. (The awkward lack of parallelism among these titles could have easily been fixed.)

While I did not always agree with Römer (more on this later), several of his extended discussions were helpful and engaging. He provides important background to his topic with an overview of interpreters who were critical or suspicious of the OT (Marcion, Schleiermacher, Harnack and Bultmann; pp. 3–6). He examines the numerous biblical descriptions of God that use feminine imagery (pp. 42–45), an aspect of Scripture often overlooked. In his discussion of divine cruelty, Römer observes interesting similarities between Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac and Jephthah’s of his daughter (pp. 48–63), as well as similarities between Jacob wrestling with God and Moses being attacked by God for not circumcising his son (pp. 63–69). Römer’s rationale for Israel’s legal system as established in the Torah is insightful (pp. 98–103), particularly his perspective on the law of retaliation, an “eye for an eye” which was intended to “avoid gratuitous and disproportionate revenge” (p. 100). In his discussion of the origins of violence based on the narrative of Cain and Abel (pp. 107–116), he makes numerous helpful observations about the ancient Near Eastern context as well as the Hebrew text (“Abel” means vapor, translated as “vanity” in Ecclesiastes). Römer’s section entitled “A God of Surprises” (pp. 139–141) is a pleasant surprise toward the end of the book, as it briefly traces unexpected ways God interacted with two of his prophets, Elijah and Jonah.

I suspect that most of Themelios’ audience will find in Römer’s book more weaknesses than strengths. Theologically oriented readers will find his non-supernatural interpretation of Israel’s story frustrating, or perhaps even offensive, but to his credit he is consistent in this regard. Römer will often state definitively the standard historical-critical conclusions about the OT as if they were proven facts, even ones that have been recently questioned by liberal scholars, as well as ones that were never accepted in the first place by conservative scholars. Römer argues that the significant evidence of Israelite idolatry would suggest that polytheism was Israel’s official religion (p. 10), but he unfortunately does not define “official.” Despite the practices of many of Israel’s leaders, the authors of Scripture were clearly not advocating polytheism. Römer speaks of an “anonymous prophet called Deutero-Isaiah” whose oracles are contained in Isa 40–55 (p. 17), but the issue is more complicated than he makes it seem. His argument that YHWH’s name originally meant “he who blows” (p. 23) will not likely convince many readers.

Römer takes texts with unorthodox perspectives and assumes they are clear, where other texts generally perceived to be straightforward he takes to be late editions without a historical basis. His conclusion that conquest narratives were not historical documents (pp. 76–91), which conveniently “solves” the problem of a genocide-commanding God, will not convince any in his audience who interpret the book of Joshua as a record of actual events orchestrated by God. In his discussion of Joshua, Römer attributes significant sections of the narrative to Deuteronomistic redactors, who revised Joshua in the exilic context to emphasize respect for Torah and not a value on warfare (p. 81). Elsewhere in the book Römer makes similar detailed arguments for late editing of texts; however, I would be surprised if many of his popular readers (his stated audience) were particularly interested in issues of Deuteronomistic redaction. Römer saves some of his most unorthodox interpretations for his latter chapters. He wonders if the serpent in the garden was actually obeying God’s orders (p. 95) and suggests that YHWH actually wanted the first humans to transgress by eating the forbidden fruit in order to be free (p. 97).

While most evangelicals will not be persuaded by his arguments, because of Römer’s insights into the Hebrew text and into the ancient Near Eastern context, Dark God will enlighten many readers about the troubling texts of the OT.

David T. Lamb

David T. Lamb

Biblical Theological Seminary

Hatfield, Pennsylvania, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

Too often people think of the Reformation in terms of an abstract theological debate...

Abstract: Evangelical Faith and the Challenge of Historical Criticism, edited by Christopher Hays and Christopher Ansberry, argues that evangelical scholars have failed to embrace historical criticism to the extent that they could and should...

Thomas Prince, editor of The Christian History—the first religious periodical in American history—could hardly have invented the Great Awakening, as Frank Lambert argues...

Theology is first and foremost about who God is and then about what he has done...

I would like to consider several elements in reviewing Bray’s work...