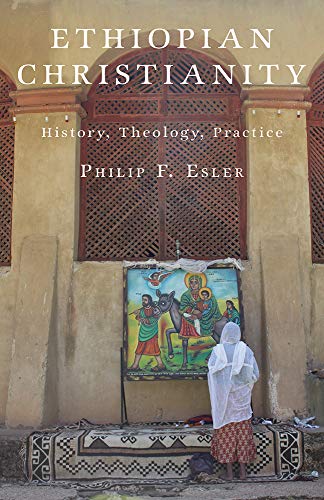

Ethiopian Christianity: History, Theology, Practice

Written by Philip F. Esler Reviewed By Abeneazer G. UrgaPhilip F. Esler is Portland Chair in New Testament Studies in the School of Education and Humanities at the University of Gloucestershire. In Ethiopian Christianity, Esler introduces readers to the distinctive features of Christianity in Ethiopia.

Chapter 1 details the uniqueness of Ethiopian Christianity because of several factors. First, Ethiopian emperors acted as patrons of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity (335–1974 CE). Second, the geographical location of Ethiopia enabled the people to maintain the traditions of Ethiopian Christianity. Esler argues that Ethiopian Christianity is a cultural amalgam of Judaism, Syriac and Coptic Christianities, and African religion. Along with the Oriental Orthodox churches, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (EOC) subscribes to a “miaphysite” Christology rather than Chalcedonian Christology. Although the EOC dominates the terrain of Ethiopian Protestantism, Catholicism and Islam also coexist alongside it.

Chapter 2 presents the introduction of institutional Christianity in the 4th century CE. During the reign of King Ezana, the spread of Christianity progressed. Confined initially to Greek-speaking merchants in Aksum, Christianity began to spread due to their effort to evangelize the Aksumites. Ezana likely converted after Frumentius’s return from Alexandria and then cautiously began contextualized evangelism efforts.

Chapter 3 overviews the state of Christianity between the 5th and 17th centuries. After Ezana’s reign, the Ethiopian kings continued to produce coins with crosses on them to spread Christianity under their patronage. The effort of Christianization and building churches with the royal army’s support extended as far as Yemen. Following Pachomius’s cenobitic-style monasteries, the Nine Saints built monasteries to train and evangelize Aksum. They also engaged in Bible translation. The Golden Years of Aksum dwindled with the rise of Persian and Islamic powers in Arabia and North Africa. Christianity, however, was penetrating the regions south of Aksum. The expansion of Christianity continued in the period of the Zagwe dynasty (1137–1270). The kings of Zagwe built numerous churches in the region. In 1270, the Solomonic dynasty came to power with the reign of Yekunno Amlak. The kings in the Solomonic dynasty utilized Kebra Nagast, a 14th-century national epic, to establish the notions that the kings descended from King Solomon, Moses’s tablets were housed in Aksum, and Aksum was the New Jerusalem. The 16th and 17th centuries were tumultuous for Ethiopia as Christians dealt with the Muslim and the Oromo invasions and a civil war due to the imposition of Roman Catholicism under Susenyos I’s directive. The EOC tradition was threatened and several invaluable artifacts, monasteries, and churches were destroyed.

Chapter 4 covers the period between the mid-17th century to the present. The country recovered from invasions and civil wars, but the political turmoil echoed that of the Old Testament judges. The EOC played a significant role in gluing the society back together and creating a national identity. Nevertheless, Emperor Tewdros II and subsequent emperors labored to unify Ethiopia. The Solomonic dynasty ended with the death of Haile Selassie and with the rise of the Derg, which confiscated lands from the EOC and gave Muslims and the Pentecostals freedom to conduct public worship. As a result, the EOC began losing its grip as the state religion. However, the anti-religious sentiment would later affect the Protestant churches due to the Derg’s embrace of socialism. After the fall of the Derg, the present regime came to power in 1991. Religious entities were free to practice their beliefs. The EOC experienced internal conflicts between the Abunas in the diaspora and in Ethiopia. Nonetheless, the current Prime minister, Dr. Abiy Ahmed, was able to mediate and reunify the two factions in 2018.

Chapter 5 overviews the intellectual and literary traditions of Ethiopia. Writing has existed in Ethiopia since the 7th century BCE. Later, the invention of Ge’ez and the expansion of writing assisted the literary traditions in Ethiopia. Monasteries played a significant role in Bible translation and the preservation of various manuscripts such as 1 Enoch, Jubilees, and the Ascension of Isaiah.

Chapter 6 discusses the EOC’s art, architecture and music. Esler identifies eight periods (4th century–20th century CE) where EOC Christian art developed. Although Ethiopian artistic traditions have their own unique style, Western artists have contributed to Christian art development in Ethiopia. The EOC also contributed in the areas of architecture and music. The cathedral of St. Mary Zion and Lalibela’s churches are some notable examples of architecture found in Ethiopia. When Jerusalem fell in the 12th century, Lalibela’s churches were constructed to establish the New Jerusalem in Ethiopia. Regarding music, St. Yared is considered to be the one who invented the “music and chant of Ethiopian Orthodoxy … [and] musical notation (p. 166).

Chapter 7 delineates the theology of the EOC. Ethiopia and her churches are considered sacred, reflecting the Jewish roots of EOC’s theology. The EOC has also carved out sacred times like Christ’s epiphany and the true cross’s exaltation. The celebration of Mary, saints and angels occurs on annually designated days. The EOC also adopted seasons for fasting. The eucharistic liturgy is the central sacred activity of the EOC.

Chapter 8 discusses the history of Protestant Christianity in Ethiopia. The arrival of Protestant missionaries from Europe and the United States enabled evangelical Christianity to permeate the Ethiopian context. Bible translation into the vernacular, the writing of hymns, radio broadcasting, outreach to university students, the Billy Graham crusade, and Pentecostalism have played a significant role in advancing Protestant Christianity.

Chapter 9 briefly overviews Catholicism in Ethiopia. The number of Catholics in Ethiopia constitutes 0.8% of the entire population. The Catholic Church was mainly unsuccessful in Ethiopia because of the historical disaster caused by Alfonso Mendez in the first quarter of the 17th century. Since then, the aversion against the Catholic missionaries in Ethiopia has been vehement.

Chapter 10 concludes with a discussion of the future of Christianity in Ethiopia. Esler notes that Islam, ethnic, and religious conflicts are the major challenges of Christianity in Ethiopia. He proposes that a healthy ecumenism between churches in Ethiopia could alleviate many of the problems among themselves. In turn, this will help them reach out to Muslims, and create cohesion around their national identity as Ethiopians.

Esler ably overviews Ethiopian Christianity from its humble inception to its current progression with clarity and care. His work highlights the unique features and contributions of the Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity through the centuries, countering the notion in some circles that Christianity began with Martin Luther or Billy Graham. Esler’s work stands out as the most up-to-date; it does not merely cover the past history of Christianity in Ethiopia as many works do. He deals with religio-political situations in Ethiopia as recent as 2018.

However, Esler’s book excludes a major historical piece in EOC’s history: the Stephanites challenged several of King Zara Yaqob’s theological assertions that they deemed unbiblical and became martyrs. Their agenda of reforming the church precedes that of the Reformers of the 16th century. Esler also erroneously assumes miaphysite Christology to be the position of Ethiopian Christianity from its beginning. Prior to 1878, the Ethiopian Church did not officially hold the Tewahedo (Union) or miaphysite position, but had three different positions on Christology (Son of Grace, Three Births, and the Union). This controversy threatened the unity of the country, and as a result Emperor Yohannis settled the disputes by adopting the Union position.

Notwithstanding these flaws, Ethiopian Christianity is a helpful piece in understanding the genesis and expansion of Christianity in Ethiopia. If the book is read along with Tibebe Eshete’s The Evangelical Movement in Ethiopia (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2009), the reader will have a comprehensive understanding of Christianity in Ethiopia.

Abeneazer G. Urga

Abeneazer G. Urga

Columbia International University

Columbia, South Carolina, USA

Other Articles in this Issue

“How can I motivate my students more?” In theological education, as in all education, students will gain the most from our classes and programs if they are deeply motivated and therefore engaged...

For those who enjoy debates, there has never been a debate more routinely rehashed than the debate over God’s existence...

A Generous Reading of John Locke: Reevaluating His Philosophical Legacy in Light of His Christian Confession

by C. Ryan FieldsLocke is often presented as an eminent forerunner to the Enlightenment, a philosopher who hastened Europe’s departure from Christian orthodoxy and “turned the tide” toward a modern, secularist orientation...

“Love One Another When I Am Deceased”: John Bunyan on Christian Behavior in the Family and Society

by Jenny-Lyn de KlerkIn the last two decades, Bunyan studies has seen an increase in scholarship that examines his life and thought from various angles, such as the psychological experiences and socio-political convictions found in his allegorical and autobiographical works...

American Prophets: Federalist Clergy’s Response to the Hamilton–Burr Duel of 1804

by Obbie Tyler ToddMore than any event in early American history, the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in 1804 revealed Federalist clergy to be the moral guardians of American society and exposed the moral fault lines within the Federalist party itself...