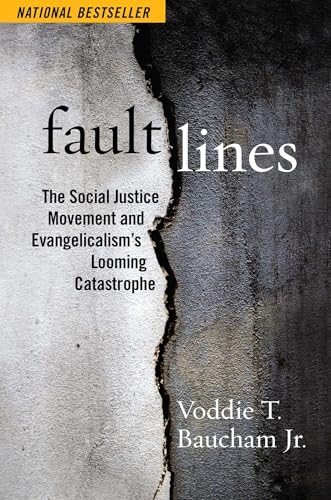

Fault Lines: The Social Justice Movement and Evangelicalism’s Looming Catastrophe

Written by Voddie T. Baucham Jr Reviewed By David RobertsonThere are not many books that have such an impact that they have made me change my mind. It turns out that Faultlines is one of them. Initially I approached the book with a degree of scepticism. After all I had heard on the evangelical grapevine that it was ‘extremist’, ‘unbalanced’, and that Baucham was guilty of ‘plagiarism’. And I am against racism and think it is a major problem in the US and the church. However, I am thankful that instead of just reading about the book, I read it myself. And I can only suggest you do the same.

Baucham’s thesis is that the current culture wars in the US over racism and Critical Race Theory (CRT) are in danger of splitting the evangelical church and causing considerable harm. He believes that the acceptance of some of the language and premises of CRT by evangelical leaders is the acceptance of a Trojan horse. He argues that ‘the United States is on the verge of a race war, if not a complete cultural meltdown’ (p. 7).

Fault Lines is not a fundamentalist diatribe or political rant. It is a well-researched, well-written and well-argued clarion call from someone who has not only studied the issues in some depth but, as a black descendant of slaves, has lived them. Fault Lines is not a detailed academic textbook, although it should be required reading for all evangelical students. It is, as Baucham stated in an interview, “the view from 35,000 feet.” If you are confused about what CRT is (and some evangelicals even deny that it exists), then this book is an excellent primer.

His personal story is powerful. He grew up poor without a father, was bussed to a white school and has battled against racism throughout his life. He has walked the walk. Maybe we should listen to his story rather than the white saviours like Robin DiAngelo who make their living out of telling white people they are racist by virtue of their skin colour? The notion that if you are white, then you are racist is itself racist. For Christians we need to ask what has the priority: our skin colour, our culture or our identity in Christ?

Baucham is controversial—at times breathtakingly so. For example, he points out that he had never heard of a black pastor arguing for racial reconciliation or lamenting that their church was 99% black. He states the incontrovertible truth that Africans sold Africans into slavery—to Arabs and to Europeans. And the not so incontrovertible view that ‘America is one of the least racist countries in the world’ (p. 201).

One highlight is the exposure of the false narratives that play such a part in the impressions that many of us base our opinions upon. Some quotes stunned me: ‘We’re literally hunted EVERYDAY/EVERYTIME we step outside the comfort of our homes’ (NBA star LeBron James, p. 45). Or the oft cited and completely false claim from the National Academy of Sciences that ‘one in every 1,000 black men and boys can expect to be killed by police in this country’ (pp. 47–48). That would mean that 18,000 black men and boys would be killed by police. The facts are that, in 2014, 250 black men were killed, of whom only 19 were unarmed. In 2019, the figure was nine (p. 113). How we interpret facts is also crucial. What do you do with the fact that 96% of those killed by police are male? Is this de facto proof that the police are discriminatory against men?

Baucham’s strongest and most important insight is that in dealing with anti-racism, we are dealing a with a new religion—complete with its own cosmology, law, priesthood and canon.

Evangelical leaders such as Matt Chandler, John Piper, David Platt and others are all gently taken to task for citing and taking on board aspects of CRT—such as using material like Peggy McIntosh’s now-famous 1989 paper, ‘White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack’. Baucham’s concern (which in Platt’s case he unpacks in some detail), is that Bible teachers are proclaiming that they have had some ‘life altering revelation that has not been derived from the Scriptures’ (p. 126, emphasis original). He rightly sees this as an attack on the sufficiency of Scripture.

The only problem with this new religion is that it is a religion without salvation. As Douglas Murray points out in a short but insightful chapter in The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), there is no forgiveness in the modern progressive world. In CRT terms, if you are white, you are guilty—and there is no redemption. ‘Antiracism offers no salvation—only perpetual penance in an effort to battle an incurable disease. And all of it begins with pouring new meaning into well-known words’ (p. 67). I’m so thankful that a black brother is speaking out against this inverted racism, distorted language and despairing legalism.

Baucham uses the category of ‘ethnic Gnosticism’—i.e., ‘the idea that people have special knowledge based solely on their ethnicity’ (p. 94)—and point outs the way in which many are misled by their reliance on narratives, rather than ‘things like facts, statistics, or the scientific method’ (p. 88). He writes, ‘I am weary of hearing testimony after testimony of white pastors who threw reason and Scripture out of the window because of narratives’ (p. 112). He not unreasonably asks: How many of these narratives were lies? How many exaggerations? ‘And how many were the genuine expression of fear and trauma that, though sincere, directly contradicted the facts? The answer is, we don’t know’ (p. 112).

In chapter 9, ‘Aftershock’, Baucham deals with another cultural issue which is dividing the US church—that of abortion and single-issue voting. It is an awkward one. But we need to ask the awkward question: While it may be wise and practical to ask if we should vote or not vote for a particular party based on one issue, how many church leaders would urge people not be single issue voters on the sin of abortion, but would then not apply the same standard to the sin of racism?

Baucham suggests that racial identity politics is not just eating apart the American church, but is affecting many mission organisations throughout the world. To dissent from the general narrative is, as he points out, to be condemned. As someone who has been cancelled by a Christian magazine in the UK because the editor eventually thought my published article could have been misconstrued as not sensitive enough to racial issues, I can only empathise!

It seems as though the American church, having taken a disastrous turn into (largely but not exclusively) right wing politics, is now in danger of overcompensating and repenting in a progressive, rather than a biblical, direction. Fault Lines exposes this and thus is largely a book about American cultural wars and American church politics. This is simultaneously a weakness and strength. It’s a weakness because it is culturally bound, but a strength because what happens in America does not stay in America. In a globalised world with globalised Christian corporations run largely along American cultural lines, all of us are impacted. It would not be the first time that American culture wars were exported to the rest of the worldwide church—to our detriment.

Fault Lines is an important, insightful and inspiring book. I’m grateful to God for its prophetic message. But don’t just take my word—read it for yourself. Here’s a final taste:

This book is, among many things, a plea to the Church. I believe we are being duped by an ideology bent on our demise. This ideology has used our guilt and shame over America’s past, our love for the brethren, and our good and godly desire for reconciliation and justice as a means through which to introduce destructive heresies. We cannot embrace, modify, baptize, or Christianize these ideologies. (p. 204)

David Robertson

David Robertson

Scots Kirk Presbyterian

Hamilton, New South Wales, Australia

Other Articles in this Issue

Ben Sira’s Canon Conscious Interpretive Strategies: His Narrative History and Realization of the Jewish Scriptures

by Peter BeckmanThis paper will outline the canon-conscious worldview of Ben Sira, highlight the major contents of his authoritative corpus of Jewish Writings, and describe his hermeneutical strategies...

Scholarly discussions concerning the nature of OT hope are arguably most passionate and divisive when the figure of the anointed one (often designated the messiah) is in view...

Raised up from the Dust: An Exploration of Hannah’s Reversal Motif in the Book of Esther as Evidence of Divine Sovereignty

by Justin JacksonThe book of Esther presents a challenge for many modern interpreters, since the book does not mention the name of God or his direct action...

Christians have long wrestled with how to read the Law in light of the work of Christ...