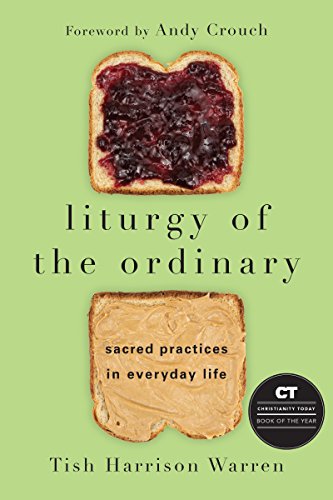

Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life

Written by Tish Harrison Warren Reviewed By Nathan A. FinnEvangelicalism is replete with calls for a “radical” or “extraordinary” or even “revolutionary” approach to the Christian life that turns the world upside down. These sorts of exhortations are never as groundbreaking as their titles and press releases imply, but they can still leave the impression that your spiritual walk is going nowhere if you are not changing the world. Tish Harrison Warren is far more concerned with everyday faithfulness than heroic spirituality. And everyday faithfulness does change your world, moment-by-moment, day-by-day, over the long haul of the Christian life.

Warren is an ordained priest who is part of the Anglican Church of North America. She has past experience in parish work and campus ministry with InterVarsity at Vanderbilt University and University of Texas at Austin. At present, she works for InterVarsity’s Women in the Academy & Professions initiative and has a growing wider ministry as an author and speaker. Liturgy of the Ordinary is her first book. And it is a good one. Rather than focusing on the place of mountaintop experiences and dramatic consecrations (and re-consecrations) in the Christian life, Warren draws upon her liturgical sensibilities and real-life experiences as a wife and mother to alert readers to ways we can experience God in the everyday rhythms of our life. In so doing, she is a modern-day Brother Lawrence who wants to help believers to “practice the presence of God” and thus sanctify their ordinary experiences.

Over the course of eleven chapters, Warren highlights everyday practices that can function as means of sanctifying grace when we approach them from the posture of faith in Christ and a desire to love God and neighbor. Waking up well becomes a reminder that, “How I spend this ordinary day in Christ is how I will spend my Christian life” (p. 24). Warming up leftovers is a call to “eat such things are as set before me, to receive the nourishment available in this day as a gift, whether it looks like extravagant abundance, painful suffering, or simply a boring bowl of leftovers” (p. 65). Even the mundane, oft-frustrating task of checking email reminds us that “vocational holiness in and through our work” helps us to “resist the idolatry of work and accomplishment,” helping transform work into a form of prayer (pp. 100–1). Other ordinary practices Warren encourages readers to sanctify include making the bed, tooth-brushing, responding well to losing one’s keys, reconciling well after spousal disagreements, idling in crowded traffic, talking with friends on the phone, drinking tea, and sleeping. Each offer windows into similar habits or responses to everyday situations that can help us mature in our faith.

It is not surprising that Warren uses liturgy as her metaphor for capturing acts of everyday devotion; she is, after all, an Anglican priest. But careful readers will not miss the influence of James K. A. Smith’s approach to liturgy as “formative practices” in the background. Smith has focused his scholarly treatises Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009), Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), and Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017) on applying liturgical insights to larger cultural institutions. But even his excellent condensed work, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2016), is still written at a semi-academic level. In many ways, Warren takes Smith’s more technical treatment of a liturgical approach to culture, popularizes it, and applies it to the “micro-culture” that is every individual’s or family’s particular experiences. The results are rich, striking the perfect balance between being lyrically pithy, yet spiritually profound.

Some potential readers who are part of less overtly liturgical churches might be turned off because of the book’s title. That would be a mistake, since Warren’s insights do not necessitate that one embrace the sort of liturgical approach to public worship found in Anglicanism and other “High Church” traditions. Others, including many readers of this journal, might be hesitant to read Liturgy of the Ordinary because Warren is an ordained clergywoman who holds to an egalitarian view of gender roles. That would also be a mistake, since each of us can learn much that is true and helpful from those we disagree with on this and other secondary issues. Furthermore, other than simply mentioning at points that she is a priest, Warren keeps her view of women in ordained ministry in the background, since it is not relevant to the point of her book. Still others who do read the book might wish for a more robust discussion of the ordinary means of grace of preaching, public prayer, and the Lord’s Supper, and/or classical spiritual disciplines such as personal prayer, fasting, Scripture meditation and memorization, etc. But these topics are not the point of Warren’s book. Liturgy of the Ordinary is meant to supplement what readers already believe (and presumably practice) when it comes to spiritual disciplines.

Liturgy of the Ordinary is a delightful book that should find a receptive audience among evangelicals of all stripes and types. Pastors and teachers will gain a wealth of insight about ways to help those whom they lead to pursue Christ in their everyday experiences. The book is perfect for church reading groups, supplemental devotional reading, or a secondary text in spiritual formation courses. Highly recommended.

Nathan A. Finn

Nathan A. Finn (PhD, Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary) serves as provost and dean of the university faculty at North Greenville University. He is co-editor of the forthcoming volume Historical Theology for the Church (B&H Academic, 2021).

Other Articles in this Issue

Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age explores the implications of Western civilization’s transition to a modern secular age in which theistic belief has not only been displaced from the default position, but is positively contested by various other options...

While encrusted generational layers of pious reverence for Abraham have made him out to be a hero of faith, he was not yet one when called at seventy-five...

The acts of white supremacy that took place in Charlottesville, VA should encourage the church to act aggressively to deter racist ideals within her ranks...

Isaac Watts is well known as a hymn writer, but he also wrote significant works on the place of passion in the Christian life...