Editors’ note: Last month on the anniversary of the Ferguson verdict, TGC hosted a webcast on race in America with NFL tight end Benjamin Watson and TGC Council member Darrin Patrick (pastor of The Journey in St. Louis, near Ferguson). More than 1,500 of you joined us during the event and afterward on social media to chat with Watson.

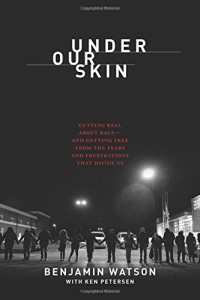

If you missed the special or would like to join in again, you’re welcome to watch it above or read the slightly edited transcript below. Once you’re done, make sure to pick up a copy of Watson’s book, Under Our Skin—Getting Real About Race, and Getting Free from the Fears and Frustrations that Divide Us.

Darrin Patrick: Benjamin, we’re in St. Louis, just miles from Ferguson. And about a year ago, you were playing the Baltimore Ravens in the Superdome.

Darrin Patrick: Benjamin, we’re in St. Louis, just miles from Ferguson. And about a year ago, you were playing the Baltimore Ravens in the Superdome.

Benjamin Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: And the whole world, though, wasn’t watching Monday Night Football for once, their eyes were on Ferguson. Do you remember when you saw what was happening, what you felt?

Watson: Yeah, I do. We were playing Monday Night Football, the season had been going so-so. We were playing the Baltimore Ravens. And, I can remember preparing for the game, and we knew that at some point the decision was going to be made. It’s crazy that I was even able to watch some of the stuff, because during the NFL season you’re just thinking about football. And so I remember going through the game, Monday Night Football ends really late. Fortunately for us it was a home game, we lost, which was doubly bad. And then, I remember my wife telling me they’d made a decision in the whole Ferguson case. And this is about 11:30 or so.

Patrick: So are you at home or is she texting you or what?

Watson: I’m actually, she’s at the game, and so after the game, you know I get dressed, do the interviews, whatever. Come out to meet her, and the first thing she says was nothing about the game. She says, “They made a decision,” because her Facebook, her Twitter, all that stuff was blowing up. And everybody had a response, and so I asked and then she told me what the decision was. And I had been watching this since it happened in August. When it first happened in August we were in training camp. And so we were at The Greenbrier, which is in West Virginia, training camp, I turned the TV on at night after a training camp day and kind of saw the incident and what happened. And so I’d been following it on CNN, or Fox News throughout the last few months, and was really interested in seeing what was going to happen. I heard all of the pundits had their ideas, and you can remember all the political activists, you can remember the protests, you can remember the different lawyers coming on the shows and talking about what they thought would happen. And so there was this tremendous buildup to that date. And so when it happened I had a lot of, a lot of emotions like everybody else did. And so I can remember coming hope, we live about 15 minutes from the Superdome. I remember coming home, going upstairs to my room, and I didn’t really think about the game, turning on the TV, seeing some of the unrest that was going on, you know, not too far from here. You know, and just seeing those images that were in my head, and kind of reflected what was in my heart and in the heart of a lot of, a lot of people. There was such turmoil at that point.

Patrick: So when you saw that, as a black man . . .

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: And you were thinking, What am I going to do about that? Why did you sit down and type out this now-infamous viral post?

Watson: A lot of times when I have feelings, I write them down. It wasn’t the very first time. I’ve written some other things, mostly about football, about my faith, combining the two, kind of seeing lessons in between. This was the first time I really ventured out, I think, and really talked about such a divisive social issue. And I didn’t know what to do, to be honest with you. I knew I wanted to do something, and I knew there was a lot I was thinking about, and when you play on Monday night, you have Tuesday off, in general. But then you’re right back on Wednesday. And so between Monday night and Tuesday I was trying to figure out what I was going to do and how I felt. And what I wanted to say. And within that time, I sent it off, and my phone actually died, and it was my wife who told me, “Did you write something on Facebook? Because my Facebook’s going crazy.”

Patrick: So you wrote the whole thing with your thumbs?

Watson: Yeah, with my thumbs. Yeah, yeah. That’s what we’ve come to in America now. We’ve come to a point where we can do all of that on an iPhone on the Notes app, not even on a word processor.

Patrick: So you didn’t like, edit it, nothing, just write, just boom?

Watson: I thought a lot about it. I erased some things, and re-did some things, and you know, thought about it, and did I really want to do that. But I knew that I wanted to write something about how I felt. Because again, this was something that the entire world, I think, was paying attention to.

Patrick: So, that little note app turned into a Facebook post, that, let me get this right. 900,000 likes, 500,000 shares and almost 90,000 comments.

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: And, that post is really what turned into your book, Under Our Skin.

Watson: And at the time I didn’t even know how to post to Facebook. I had a website, you know, because I’m an athlete, and athletes are supposed to have websites, and Facebook and Instagram and all that stuff. And so my publicist was saying, you know, “We’ve got to do this Facebook thing,” I said “okay.” So they just put stuff up there, fan page, that sort of thing. And so I actually had to send it to them, say, “Would you put this on Facebook for me?” And they put it on there. So now I know about it, now I’m involved with Facebook now, but at the time I wasn’t even involved. And then, that happened, which was really surprising to me.

Patrick: So that post really was the catalyst for this book that we’re talking about, Under Our Skin.

Watson: Yes, yes.

Patrick: Why a book?

Watson: It was offered to me, and it was a proposal, and there was an idea from the literary agent that this may work: a book. And I’m saying, “No, not me, write a book, I can’t write a book, I gotta go to training camp, I don’t have time to write a book.” But over the course of a few months I really got my thoughts together, and kind of, Under Our Skin is an expansion of the Facebook post.

Patrick: Yep.

Watson: What was your response to Ferguson?

Patrick: Well . . .

Watson: As a white man?

Patrick: Yeah. I grew up in a rural community, just south of St. Louis. A racist community, quite frankly. But I was an athlete and so, tons of my friends were black, and I liked hip-hop, and we played sports and we had fun together, and so I never really thought much about it. But when Ferguson happened for me, it exposed some stuff in me that I don’t think I really knew about myself. You know, I’m a pastor in a multi-ethnic church, in a racially divided city. But when I saw the response of our city to that event, I thought, Well . . . why? What’s the outrage? I mean I get it, but I didn’t get it. To the point that I had to come in front of our church and repent, because I I thought I knew but I didn’t know. And I still don’t know.

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: But I realized, man, there’s some stuff going on in my heart, and I liked the phrase in your book “living room racist.” I think I had some of that in me, and I I didn’t even realize it until I just saw my response to the city’s response.

Watson: Yeah, yeah. And I think that’s what I saw after the post. Is that people were saying, white and black, they’re saying, you know, “That’s kind of what I wanted to say but I didn’t know quite how.” But also they were saying, “Man, it’s kind of challenging.”

Patrick: Yeah, “How dare you,” right?

Watson: Yeah, exactly, like how are we were responding to these things and we respond differently. You know, we all have our own lenses that we grow up with, our own assumptions that we grow up with. And then when we see these events that happen and are so polarizing, and we see the lines drawn on each side and we always find ourselves saying, “Which side of the line do I need to be on?”

Patrick: Yeah.

Watson: And unfortunately, but realistically, a lot of times we align ourselves with people that look like us.

Patrick: That’s right.

Watson: Bottom line, that’s our natural tendency as humans. And so, it’s awesome that you were able to see that, and that you were able to confront it, and that you were able to repent from it.

Patrick: Yeah.

Watson: I mean, that’s a first step when it comes to dealing with issue of race, is that it’s not a problem that’s out there, it’s a problem that’s in here that all of us have. And that we need to look inside and say where do we fit in the whole narrative of Ferguson, or the whole narrative of Eric Garner or the whole narrative of whatever it is, going back to when Africans first got here; what’s this narrative that’s been woven through the tapestry of America and how do we view ourselves in that.

Patrick: You know what’s interesting is, you know, me growing up kind of in that rural, kind of quasi-racist deal, without a dad. You grew up with a strong dad and grandfather.

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: One of the things in the book that I thought was interesting is your Pop-Pop, which is what you call grandpa, right?

Watson: Yeah, uh-huh.

Patrick: He says, “When you’re black, there’s always a ceiling.”

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: And you interacted with that idea, tell us about that.

Watson: Yeah, well, Pop-Pop was my father’s dad. Pop-Pop lived in Washington, D.C., and we grew up in Norfolk, Virginia, which is about three and a half hours away, but if my dad’s driving it’s about five hours from Washington, D.C. He’d drive below the speed limit. But we would go up there and visit him, and it was just kind of a different world. One of the things that my mother always told me that he would say was that there was only so far that you could go. And that no matter how much education you had, how polite you were, how deserving you were of a promotion or certain job, there was always this glass ceiling, and you just couldn’t break it. You know, and that was the world that he lived in. That was his reality. And, you know, for me, there’s still remnants of that that I feel sometimes. You know, obviously in my profession, it is a very, you know, athletic based profession, performance based profession, and so obviously no matter what color you are can you go out there and do it on the field. But even within that, it wasn’t very long ago where, you know, blacks couldn’t play middle linebacker because you had to make calls.

Patrick: Or quarterback.

Watson: Or quarterback, because you had to make calls. Or center, because you touch the football and you’d, maybe you—

Patrick: Or coach, or GM.

Watson: Exactly, exactly.

Watson: So there are still remnants of that that are trickled down since Pop-Pop. Pop-Pop passed away two—a year ago, a year and a half ago. And so unfortunately he’s not going to be able to read the book, but he is a very big part of my experience.

Patrick: Yeah. Some of those cultural issues, that I’ve found as well, revolve around music. And you talk about your love-hate relationship with hip-hop. Bring us into that a little bit.

Watson: You’re going to get me in trouble now. It goes deep. It goes deep, you know. Hip-hop is kind of the music of, I would say, my generation. Black, white, in between, everybody, everybody loves it. But the gripe I have is a lot of hip-hop isn’t, number one, honoring to God. And as a believer, my number one goal is to be honoring to my Lord and Savior. And I want to listen to things that push me in that direction. But they also don’t build up family, don’t build up the relationship between husband and wife, don’t respect women in a lot of ways. The language, you know, we’re told to watch our tongue, the language is deplorable sometimes.

Patrick: But I get that, but how do you . . . the music, and the creativity?

Watson: It’s beautiful!

Patrick: But how do you do that, like as a Christian man, how do you go, “I love that, but I, man . . .” Bring me into that, the song comes on the radio in the locker room.

Watson: It’s strong. Oh, you’re going to feel it. And, you know, in warm ups, you feel it, you know, you get it inside you and you’re ready to go. You know, it hits a switch, but that’s the controlling power of music. That’s not by accident.

Patrick: Right.

Watson: My whole thing with hip-hop started very young, you know, Snoop Dogg was the first thing that I heard, and I got in trouble because my little brother somehow took the tape and played it while I was at school. Tape I wasn’t even supposed to have, it wasn’t mine, it was my friend’s. So my dad, you know, heard it. When I came home he had some words for me. And you know, it wasn’t very good. That’s why I don’t like Snoop Dogg to this day, you know. I deal with everybody else but not him because he’s just bad memories. But my love-hate relationship is because it’s a beautiful music. It’s poetry, you know, it sounds good. It moves the emotions and the heart. I like the way it makes me feel, I like the sound of it. But on the other side, I see that, you know, if you’re not able to separate that, and this is life, it can promote things that are not positive for black people. Or for anybody else, but, if we’re looking at it in the realm of black people, a lot of it, some of it does, but overwhelmingly a lot of it doesn’t do things to help us move forward.

Patrick: Yes.

Watson: And when you talk about the use of the N-word in the music, it doesn’t weaken the word by continuing to use it. What it does is, it makes you not realize the power of that word, because there’s still power in that word. And it’s disrespectful to those, in my opinion, who died hearing that word.

Patrick: Yeah. So the thing I appreciated, I think the most in the book, I mean there were so many things, was your emphasis on changing the world through relationships. And what struck me is, you know, part of my repentance as I talked about, about the whole Ferguson response and my heart’s response to that response, was I realized, “Hey, I’ve had black friends in my home for meals, hung out in numerous places. But I’d never had any of my black friends over for any holidays.” And so, last Thanksgiving, right after all this, we have a single dad in our church, and didn’t really have anywhere to go with his daughter. And I had him in our house. And it was a game changer for my family. And you talk about your relationships in the book, like, bring us into some of those relationships with your white friends, and how that has helped you, shaped you, and then how that’s the way forward in this issue.

Watson: Well, the number one piece of advice that I would tell a white man, when asked about black people, is to not say, “I’ve got five black friends!”

Patrick: Yeah.

Watson: That’s like what you don’t say.

Patrick: That’s the worst thing, yeah.

Watson: That’s the worst thing.

Patrick: “I listen to hip-hop!”

Watson: “I listen to hip-hop, I’ve got five black friends! Uh . . . they came in my house one time!” You know, that’s like . . . okay, whatever, you’re a racist. You know, but no, I mean, what you’re saying is right. There’s a difference between having some black friends you see at work, and maybe at church, or at school, and having intentional living relationships.

Patrick: Yeah.

Watson: And that’s what we’re lacking. And again, the relationships, I don’t think, they don’t solve the entire problem, there has to be a change of heart, and repentance. That’s what solves it. But, it has to be intentional with people at church, with people at work, with meeting outside of those settings, with going on double dates or date night, with going to, you know, the kids’ parties with Sally and Susie and whoever. You know, getting together with those people. And that’s when the partitions are broken down and you see people as human and you see people for who they really are. So, yeah, you know, over my life I’ve had quite a few relationships with some people, and there’s a couple guys in particular that I’m able to just talk with, you know? I talk about a guy named Chris in the book, and he’s—

Patrick: Yeah, that’s where that phrase “living room racist,” yeah, talk about that.

Watson: Yeah, well he’s a bit older than me. We met within the last couple years. But we just struck up a friendship and were able to talk about these things, especially when Ferguson happened, for some reason we were able to just be honest with each other. I think it’s because we didn’t have this long history together, and it’s like, “Look, how do you feel about this?” You know, why are you upset that you feel like Affirmative Action is doing your child wrong, or you feel like, you know, the welfare system is taking away, and you’re paying into it. I talk about these things in the book, but the amazing thing is that we’re able to be friends, we’re able to get some of these questions answered and we’re able to get it off our chest. Part of the issue is that we don’t want to say certain things because we feel like somebody’s going to jump down our throat.

Patrick: Right. Yes. So there’s a phrase that you use, “living room racist,” and I want to read this from your book, and I want you to respond to it: “‘I don’t need to talk like that,’ Chris told me. ‘And I haven’t, since. Not like that. But Benjamin, I really do see things differently from you. I get angry at what governmental policies are doing to white people, like me, who are trying to make ends meet.’”

Watson: That’s an honest place for Chris to be in. That’s an honest statement for him to make. And the beauty of it is he’s able to make that statement to me, and me not jump way down his throat, and maybe a little bit, but not too far down when he says it. Because a lot of these statements—

Patrick: Honestly, when he said that . . .

Watson: Did I punch him in the face?

Patrick: Did you want to? What did you feel? Help me understand what that feels like when white people go, “Affirmative Action!” That’s basically what he’s saying.

Watson: The first thing I felt was, you don’t understand Affirmative Action, number one. You know, you don’t understand that white women benefit the most, and it’s not always about race. And that some of the facts that we see on TV or in the newspaper aren’t necessarily true. You know, you can make these facts say whatever they want to, to get a certain bias, to whatever you want it to be. And so, my first reaction isn’t necessarily anger.

Patrick: You go to research?

Watson: Yeah, I go to research because I want to have the answer. But it is a sort of defense. Because automatically I feel like you’re saying . . . what I’m hearing is, “Black people don’t deserve any help because they’re probably lazy anyway, and, you know, that they’re taking our country away.” And I’m hearing all these other things that he’s probably not even saying, but my mind will start going down that road.

Patrick: So how did you, when he said that, how did you quell that, how did you push that down and then have—because you said that was an honest answer…

Watson: It’s about the relationship.

Patrick: Okay.

Watson: It’s about the relationship. He’s not a stranger to me. If he’s a stranger, you know, saying these things, then I may go down that road and be a little bit more defensive, but I know his heart. I understand the fact that he’s actually saying this, that he’s speaking from an honest place and he’s trying to get a true answer from me.

Patrick: Let me just ask you, can you understand from a white person’s perspective, how they would view, like Affirmative Action, for instance. Like, their kid doesn’t get to go to this school because of that.

Watson: I can understand it as a father, I can understand it. If they solely believe that it’s because the black kid didn’t have as good of grades as their kid and got in, I’d be upset too.

Patrick: Yeah, but that’s not the truth.

Watson: That’s not always the truth. There are a lot of other factors that go into it. And, it might just be possible that the black kid had better grades than your white kid. I was the black kid that had better grades than a lot of white kids, and they looked at me crazy, until I had to tell them about my SAT score. That’s another story. But I can definitely understand where he’s coming from, especially when you have a child and you feel like that child deserves it and the child has great grades, and then you hear through the grapevine that they’ve got this new program to give minorities a chance. And you’re saying hold on, you know, my kid deserves it.

Patrick: Right.

Watson: I definitely feel that. And then on the other side, I can see where the minority parent is saying, “You had a 400-year head start. We should get a little bit of a chance to catch up.” You know, so, you see both sides of it, but the great thing about my relationship with Chris and other people is that he’s able to say that to me and I’m able to bring up some other possibilities. You know, and his response, “I hadn’t thought about it that way, you know, maybe it’s not just my kid is being rejected simply for being white.”

Patrick: Yeah. So, obviously, we want to move forward. How do we think about making a difference? Like, you can make a point, or you can make a difference, and I know you want to make a difference, that’s why you wrote this book. And, we can talk about, you know, doing a big group hug . . .

Watson: Kumbaya.

Patrick: Let’s make sure we got a black guy over here, and an Asian guy over here, but we know there’s a lot more to that. That the heart has to be transformed by the gospel. What would you say the fruit would be for a white guy, to know that his heart is being transformed with regard to race? What would he do differently? What would he think differently, how would he choose to orient himself relationally? Speak to a white guy here.

Watson: It’s about our reactions to issues like Ferguson. It’s about how we project our ideas about who was right and who was wrong before the facts come out. It’s about our assumptions that we have simply because of our experiences, because when your heart is changed, you are able to see things for what they really are. You’re able to have patience, you’re able to not assume about certain people, you’re able to give people the benefit of the doubt until something happens. And the way you react is not pointing the finger, it is understanding that I have some of these issues in my heart as well. It is understanding that without the blood of Christ, I’m not forgiven either. And so when you see things from that way you understand you’re not better than anybody simply because of the color of your skin. You know, you’re not. You know, you need him as much as the next person does and when you understand that forgiveness, it gives you the ability to give other people a little bit more grace.

Now, at the same time, it’s not this crazy utopia where if somebody wrongs you, you go and keep allowing them to wrong you, it’s not that. But what it is, is seeing people the way Christ would see them. You know, and the reason why, when I wrote that post, I went through the whole thing, and then I hesitated for a minute when I talked about the gospel being the answer. Because I’m an athlete and sometimes it’s cool to put the Christian thing, but not too much, you don’t want to be overtly, you don’t want to offend anybody. And then I said, “You know what, that’s the only way that we get through this thing.” Because in our own power, we can’t. We’ve tried it, we’ve tried to legislate, which is all, which is great, and we should do those things, you know, we have equal rights to vote and things like that. Those are all things that needed to happen. We talked about relationships and those are very important. We talk about education, learning about each other, learning about our past. But in the end, when I open my eyes and I see you, I still see somebody that’s different. And there’s still a lot of history behind that. In order for me to look at you and give you the same chance I give everybody else, and see you as Christ sees you, then I need my heart changed. And that happens through the gospel.

Patrick: You talk about pride in the book, and I was reminded of James 4:1, where James says, “What is the cause of quarrels and conflicts?” And the word quarrel is just like, hey we’ve got a beef, and the word conflicts is about world wars, right.

Watson: Yeah.

Patrick: He says what are the cause of that, personal beefs and wars. “Is it not your desires that wage war inside you?” So that we have to own our own depravity. And that kind of levels the ground, right, and then we can look at everybody not with a superiority complex or an inferiority complex, because the gospel basically says, not only are you not better than anybody, you’re not worse than anybody, right?

Watson: Yes, yes. And that’s key too, that’s key too because racism in and of itself is simply a faulty view of yourself. It’s faulty obviously on a spiritual level. It’s faulty on a physical level, because physically, geneticists will tell you there is a .0001 difference between you and I, and actually I can be closer to you, than somebody who looks like me genetically. And so, when you look at racism that way you understand that, you know, I’m not inferior. That’s key because a lot of black folks have an inferiority complex that’s been passed down. I’ve talked to my father about it and he tells me about, you know, when he was growing up in the ’60s, how automatically the white car salesman, or the white, you know, lawyer, you went to him before you went to the black one. And what that told him, and obviously what’s been passed down to my generation, is that the white one is better than the black one. You may not say it that way, but that’s the inferiority complex that’s been built in because of the years and years of systemic racism.

You mentioned pride earlier, and one of the evidences of a changed heart is being able to hear another’s experience that may not be your own, and not dismiss it as false simply because you don’t know it to be true for yourself. And that goes on both sides. That goes for you growing up in a rural place and for me growing up, you know, in more of a city. And you hearing how I feel about something like Ferguson, or for me hearing how Chris feels about, you know, the Affirmative Action, and not dismissing it as false simply because that’s how I feel. But when you have a changed heart you’re able to extend the grace, and hear, and listen, and you may learn something from the other person. Instead of immediately turning around and saying that, “You’re not right, that’s not true.”

Patrick: Yeah. And isn’t that what we teach our children? Don’t we want them to interact with ideas and people and not immediately judge it? And I thought, honestly, like, the book is awesome. I would encourage people to buy the book for one story, for one letter that you wrote to your daughter. And, won’t you take us through the themes of what you said to her?

Watson: I wrote a letter to my daughter, who was unborn at the time when I was writing the book. She is two and a half months old now. And just explaining, in writing this book, so many feelings came out, from talking to my parents about and my grandparents about their experiences, and you kind of get this whole picture and just telling her what she’s about to come in to. You know, as a child. As a baby. What is she about to come in to? She’s coming into a world that is fallen, that is sinful, where there is pride, where there is prejudice, where people won’t like her because of how she looks, where people that look like her won’t like her because she’s educated, which is crazy. Where people may call her names, where the ceiling, as Pop-Pop said, may be glass, and she may not be able to accomplish certain things because of who she is.

But I told her that, in this letter I told her that, no matter what people say about you, you are a daughter of God. And that I, as your father, know that you come from a long line of people who have accomplished great things. And I expect the same for you. And it doesn’t matter what people, black, white or in between say about you, you can accomplish everything you want to accomplish because of what God has put in you, and the talents that you have. And that above all else, the thing that I care about, the thing that you should care about, is how He sees you. “How does God see me?”

Patrick: And that’s a father speaking over his child, which is what the gospel is, right . . .

Watson: It is.

Patrick: The father says I’m loving you not based on your performance . . .

Watson: Your merit. Not on your merit, because we can’t earn it.

Patrick: That’s right.

Watson: The grace is the unmerited favor. You know, she has grace with me, unmerited favor. And that’s what we have with our Lord and Savior, unmerited favor. So, a lot of times we talk about our children, and I actually had a teammate call me. This was after the shooting in Charleston. A former teammate of mine, he played in the league, he actually played here in St. Louis for a while. He called me and, almost in tears, because it’s like “What do I tell my kid? You know, he was sitting in church and somebody gets shot, “What do I tell my kid?” He said his son came to him crying because his son didn’t want to go to church. And it’s not necessarily a black-white issue, but this is the world we’re living in, where crazy stuff happens. It’s like, “What do I tell my kid?”

And so as we sit with this race thing, we feel the same way. What do we tell our kids? How do we teach our kids? And for us in our house, you know, again it’s about the relationships, but it’s about telling, teaching our kids to see people as God sees them. And what I mean by that is, it’s not necessarily to see them as their race or their color, but to see them as people who need forgiveness, the same way I need forgiveness. People need the blood of Christ the same way I need the blood of Christ. And when you look at people that way, it’s amazing how different you look at people. You don’t look at yourself as better than anybody because you know that you are condemned the same way that they are, outside of the blood of Christ. And it’s amazing, the perspective that changes when you see yourself in the correct light.

Patrick: We have so many resources of the gospel. Not just the idea of atonement, which is kind of what you’re describing, that Jesus, in our place, died for our sins. Jesus lived perfectly so that we don’t have to.

Watson: Yes.

Patrick: That we can have the smile of the father because of what he did. Not just his work on the cross, though, but even on his work coming to this earth in the incarnation. He came and moved into our hood. He came and inhabited our world, and so now we have the ability, right, to imitate him, as we go and live places that are diverse, we have friendships that are diverse. We look at people who are not like us and we believe the best so that we can wade through all the other stuff.

Watson: And it’s about demonstrating that for them. We can’t expect our kids to do anything outside of what we do. If I sit here, we talked about it with Chris, you know, in the book. We talked about the faith. He said something and his daughter heard him say it, and said, “Daddy, that sounded really racist.” Our kids are picking up on everything that we do and say. They’re picking up on the little look that you give when the thing comes on TV, on CNN, and there’s folks protesting, or whatever it is, black and white they see how we respond. They watch it. It’s a tremendous teaching opportunity when these things come on, to look and see your kids looking at you, and they’re going to pick up exactly what you do. They’re going to form hypotheses . . .

Patrick: No matter what we say.

Watson: No matter what we say. Positive or negative, they’re going to pick up on how you talk about people who are black and how you talk about people who are white. Because black folks, we talk about y’all all the time. We do. And a lot of times we have to repent in front of our kids. My wife and I have had to tell our kids, you know, “We shouldn’t say that about Darrin. That wasn’t right.” But also when you talk about repentance, you know, earlier we talked about repentance, and it’s about being authentic and being real before our kids. And letting our kids know, you know, daddy and mommy, we don’t have it all together. We have some attitudes against some people, because of what other people that look like them have done. And that’s not right for us to do. And they see that, and they understand that, mommy and daddy aren’t perfect, but we’re leading them in the right place. We’re allowing them, we’re teaching them that repentance is the key to changing our heart.

Patrick: Yeah. So, what is this costing you? But I’m wondering, you know, I mean that post went viral, this book is going to sell like crazy. What is that going to cost you professionally, and even personally, to kind of put your thoughts on paper for the whole world to see? Like, what is that going to cost you, or what is that costing you?

Watson: I don’t know. We’ll see, once people read. But I can tell you that the feedback from the post, has been positive and negative. You know, but the gospel costs. Truth costs. Not even about the gospel, let’s separate that and just let’s talk about this race issue, and if we’re being honest about it, it can cost us popularity to speak out. It can cost us friendships sometimes. People want to hear something that’s nice, but a lot of times this isn’t pretty. But there’s no growth without truth. When you go in there or you work out, you break down muscle and you get stronger. I think when it comes to this racial issue, it’s still here, it’s still very painful, and we need to really be truthful and honest about it and ugly about it before it gets any better. But I believe that it can get better. So, I don’t know what it’s going to cost me, but whatever it is, I feel like God has given me an opportunity. This isn’t something that I really wanted to do, or envisioned myself doing, even writing the Facebook post. Like I said, I didn’t even know how to post to Facebook. But I feel like the opportunity has presented itself and I just want to be faithful, and speak truth. And it’s not my job to worry about what happens. That’s his job.

Use these resources to help keep the conversation going: