Daniel Silliman (PhD, Heidelberg University) is a Lilly postdoctoral fellow at Valparaiso University. A U.S. historian, he is writing the history of bestselling evangelical fiction, including Janette Oke’s Love Comes Softly. As the season finale for When Calls the Heart airs this Sunday on the Hallmark Channel—based on Oke’s series—I asked Silliman if he could help us understand the author and the evangelical tradition behind the series and the books.

When Calls the Heart doesn’t look like a theology of suffering. The Hallmark Channel show is a sweet and sentimental drama, telling the story of a cultured young woman who takes a job as school teacher on the Canadian frontier in 1910. She faces challenges. She learns lessons. She finds love, inner strength, and a supportive community.

The show is finishing its fifth season this month. And it’s a big hit. More than 2.5 million viewers are expected to tune in for the finale on Sunday, April 22. The show has already been renewed for a sixth season, and the first four seasons are available on Netflix. Online, the show has an active fan community, including a “Hearties” Facebook group with more than 60,000 members.

“It’s feel-good TV,” The Washington Post reported, explaining the appeal. “The main characters do the right thing. The problems get worked out. The guy and girl . . . always end up together.”

Mother of Evangelical Romance Novels

The story, though, with all its sweetness and light, is built on a real reckoning with tragedy. It comes out of an evangelical tradition that addressed itself to the burdened and brokenhearted.

When Calls the Heart is adapted from a novel by the same name by Janette Oke (b. 1935).

Oke, now 83, is the mother of evangelical romance novels. She wasn’t the first to write a romance novel with evangelical themes, but her success established the market for the genre, and made “evangelical romance” its own market category.

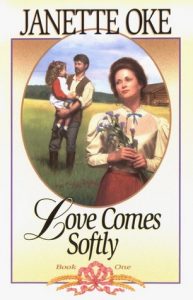

Her first novel, Love Comes Softly, sold an average of 500,000 copies per year for 20 years after its publication in 1979. Oke went on to write seven more novels in the series, plus three other series, plus another series with a co-author, more than a dozen standalone novels, some children’s fiction, and a number of devotionals.

She has had a profound and under-appreciated influence on many evangelicals, shaping their imagination. She has told story after story of evangelical faith, story after story about how a woman could trust God.

Oke had a conversion experience at 10 years old. She was Janette Steeves, then, the child of farmers on the Alberta prairie. In 1945, she was invited to an evangelistic summer camp for children. Her parents weren’t churchgoers, but they let her go, and it changed her life.

The camp was run by the Missionary Church, an association of Mennonites who had embraced revivalism. One thing that set the Missionary Church apart in Western Canada was its women ministers. On the “needy prairies,” the church authorized at least two dozen ministering sisters to organize revivals, preach, and plant churches. The church in Hoadley, Alberta, for example, was founded by Pearl Reist. In the middle of the Great Depression, 38-year-old Reist took over a pool hall, built a pulpit out of wooden crates and pews out of nail kegs, and began to preach. Eleven years later, the church was sponsoring farm children for a summer camp at nearby Gull Lake. The evangelist, that summer, was another ministering sister named Beatrice Speerman Hedegaard.

Hedegaard preached to the prairie children about yielding their lives to Christ. It wasn’t enough to read the Bible stories, she said. It wasn’t enough to believe God existed. It wasn’t enough to say that Jesus died for your sins. To really believe, you needed to turn everything over to Jesus and truly, totally, give your life to God.

Young Janette sat through altar call after altar call, her heart beating hard, her palms all sweaty. She wanted to go forward. She felt a longing that almost pulled her out of her seat, she wanted to go forward so bad. But she was afraid she’d be embarrassed in front of all the other children.

Finally, one night, Hedegaard didn’t give an altar call. Instead of asking people to come forward, she told the children if they wanted to give their lives to Jesus, they should just raise their hands. Janette’s hand went up. Then Hedegaard said, if your hands was up, you should come forward.

Remembering this episode years later, Oke mostly remembered the feeling of relief as she went forward. She felt free. She was free from embarrassment, free from shame, free from the fear that kept her locked in her seat for so long. It was, she said, just a “wonderful realization of forgiveness.”

This became the core of Janette Oke’s theology. She believed in the power of yielding your life to Jesus and trusting God.

Her favorite hymn was written by a Linda Shrivers Leech, a Methodist organist. The hymn goes,

God’s way is the best way

God’s way is the right way

I’ll trust in him always

He knoweth the best

It’s sweet. And some might think the theology sentimental. But Oke found this practice of trusting God was sturdy enough to bear up under the greatest sorrow. This was the hymn she sang to herself at 22, when she had a miscarriage.

Reckoning with Reality

Janette married a young man from the Missionary Church, Edward Oke. In 1957, the young couple moved from Alberta to Indiana, where Edward took classes at Bethel College. He was going to be a minister. She was pregnant.

They had only just arrived and unpacked their belongings when Oke had a miscarriage. She was alone in their $65-a-month apartment, far, far from her mother and sisters. There was no doctor, no trusted friends, and no pastoral counseling.

It was just Janette, her pain, and God.

Oke laid down on a fold-out bed and cried. And as she cried she decided again to give everything to Jesus. She decided to trust him and she gave him her baby and her sorrow. She sang the hymn again,

God’s way is the best way.

God’s way is the right way.

I’ll trust in him always.

He knoweth the best.

The next year Edward graduated and started seminary at Goshen College. He took a position as an assistant minister at a nearby Missionary Church, and Janette started working in the mailroom at a manufacturing company. Sometimes she taught Sunday school. Life seemed to be good to the Okes.

Then Janette got pregnant again.

Her joy was mixed with fear. Oke prayed, though, and felt comforted. She gave God her baby and her fear. It comforted her.

Oke gave birth to a son in October 1959. But the infant had a heart murmur and an enlarged liver and the doctors didn’t know why. They whisked him away and tried to save him while Oke lay in her hospital bed, unable to do anything. Then they came back. Her son was dead.

In her apartment, alone, she thought the same thing over and over again: I didn’t even get to hold him. I didn’t even get to hold him. She spent days looking at the empty crib, just crying.

She said to God, “I know I said you could take him—but I didn’t promise not to cry.”

Let Go and Let God?

Sometimes this revivalist theology is summarized as “let go and let God.” And sometimes, it’s understood as a kind of prosperity gospel. If you give up and surrender, it’s said, God will give everything. Abundant life! Fullness. Your days will be sweetness and light.

But for Oke, that’s not what it meant to let go and let God. To really yield and really give everything to God meant also giving up any idea of what abundant life was supposed to be like. You couldn’t trust God and get a Mercedes. You could trust God and get God. You couldn’t yield your pregnancy to God and get back the baby you always wanted. But you could know Jesus was holding your baby, your mourning, your deepest pain, and know he loved you—loved you so much—and your sorrow was his sorrow, your loss was his loss, your ache was his broken heart.

If you give your life to Jesus, Oke believed, you can know how much he loves you, and his love can comfort when life is hard.

This is the theology Oke put in her romance novels. Her first novel, published by Bethany House in 1979, starts with a woman suddenly widowed, alone and afraid on the frontier. By the end of Love Comes Softly, the protagonist tells God, “Ya be comfortin’ me, and I be grateful for it.” She says, “I thank ye, Lord, that ye be teachin’ me how to rest in you.”

This is the theology Oke put in her romance novels. Her first novel, published by Bethany House in 1979, starts with a woman suddenly widowed, alone and afraid on the frontier. By the end of Love Comes Softly, the protagonist tells God, “Ya be comfortin’ me, and I be grateful for it.” She says, “I thank ye, Lord, that ye be teachin’ me how to rest in you.”

It was Augustinianism in a bonnet, in a made-up prairie patois. It was evangelicalism for the everyday lives of women who knew how life could be. It was story for all those who are weary and burdened, who just wanted to give the weight of their lives over to Jesus. It resonated with a lot of people.

Hallmark Version

Janette Oke’s faith in yielding to God doesn’t always translate to the TV series. When Calls the Heart is not plotted around conversion, and the religious elements are mostly relegated to the background, the moral norms setting the scene like the Canadian landscape. There are no revivals and no born-again experiences, as there are in the books. Brian Bird, who co-created the show with Michael Landon Jr., explains the show is trying to be more subtle. He says, “I believe all human beings have these violin strings running through our souls. These strings, when you pluck them, they reverberate with certain themes like forgiveness and redemption and sacrifice and courage and banding together to help one another.”

An estimated 2.5 million viewers will tune in to those reverberations on Sunday. More will watch it when it goes to Netflix, probably later this year. And some of those will glimpse in the show the deeper theology behind the original books—an evangelicalism contextualized and addressed to burdened and brokenhearted women.