National Geographic reports:

Archaeologists tunneling beneath a Palestinian neighborhood just south of Jerusalem’s walls are uncovering a monumental stepped street that led to the foot of the Temple Mount, the sacred platform that once held the Jewish Temple and now is home to some of Islam’s holiest sites.

The impressive walkway stretched more than a third of a mile, was 26 feet wide, and required some ten thousand tons of limestone slabs. “We think it was a single project built at one time,” says Joe Uziel, the Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist in charge of the effort. Uziel and his colleagues recently published their findings in Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology.

Historians long assumed that the Roman-appointed King Herod the Great, who died around 4 B.C., was responsible for most of the great construction efforts that transformed ancient Jerusalem into a major pilgrimage and tourist center. But analysis of more than 100 coins found beneath the stepped street point to the start and completion of the effort under Pilate, who ruled for about a decade starting in A.D. 26 or 27.

The latest coins discovered beneath the paving stones date to around A.D. 31. The most common Jerusalem coins from the first century were minted after 40, “so not having them beneath the street means the street was built before their appearance, in other words only in the time of Pilate,” says Donald Ariel, a coin expert with the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The article quotes two archaeologists on the significance of the discovery if Pilate was involved:

Tel Aviv University archaeologist Nahshon Szanton, the lead author of the study, speculates that Pilate’s construction of the street “may have been to appease the residents of Jerusalem,” as well as to “aggrandize his name through major building projects.” In A.D. 70 the street was buried under rubble following a revolt between Jewish groups that led to the Roman destruction of the city. Many of its slabs were subsequently reused for later projects.

Matthew Adams, director of Jerusalem’s W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, who was not involved in the work, says the results provide insight into the time when Rome exerted direct control over Judaea. “It also provides some evidence of cooperation between the Roman authorities and the Jewish religious authorities,” he adds, noting that most known sources emphasize tension between the two.

But there is reason to question the dating:

But Jodi Magness, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is not wholly convinced. “The material they are finding is coming from fills that might have been brought in with wheelbarrows from anywhere, so I’m skeptical of the dating,” she says. “It is not impossible that Pilate was responsible for the construction, but that is not the only, or even the most likely, possibility.”

I posed the question to Leen Ritmeyer, the world’s leading expert on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. No one has more experience in the combination of architecture and archaeology in Jerusalem. He was the lead consultant behind the archaeological drawings in the ESV Study Bible.

This street has been known for more than 100 years and parts were excavated by Bliss and Dickie around 1890, by Hamilton in the 1930s and Kenyon in the 1960s. A large stretch was excavated by Mazar in the 1968–1978 excavations in which I participated. In 1975, I was able to draw a plan of the whole street from Robinson’s Arch to the Siloam Pool, which incidentally continued north to the Damascus Gate.

At present the southern half of this street is being excavated below ground, more or less under the present El-Wad Street. One can walk on this street starting near the Siloam Pool and walk halfway up.

It is also possible to walk through the sewer below this street all the way up to Robinson’s Arch.

I don’t believe that Pilate had anything to do with it, as the coins that were found under the street in our dig dated to about AD 54. We therefore believe that the street was built by Agrippa II. [Note: This is the Agrippa who heard Paul’s case at Caesarea Maritima in Acts 26, probably around AD 59.]

To build a street like this through a valley, soil from different places had to be transported, and therefore the AD 31 coins may have come from elsewhere.

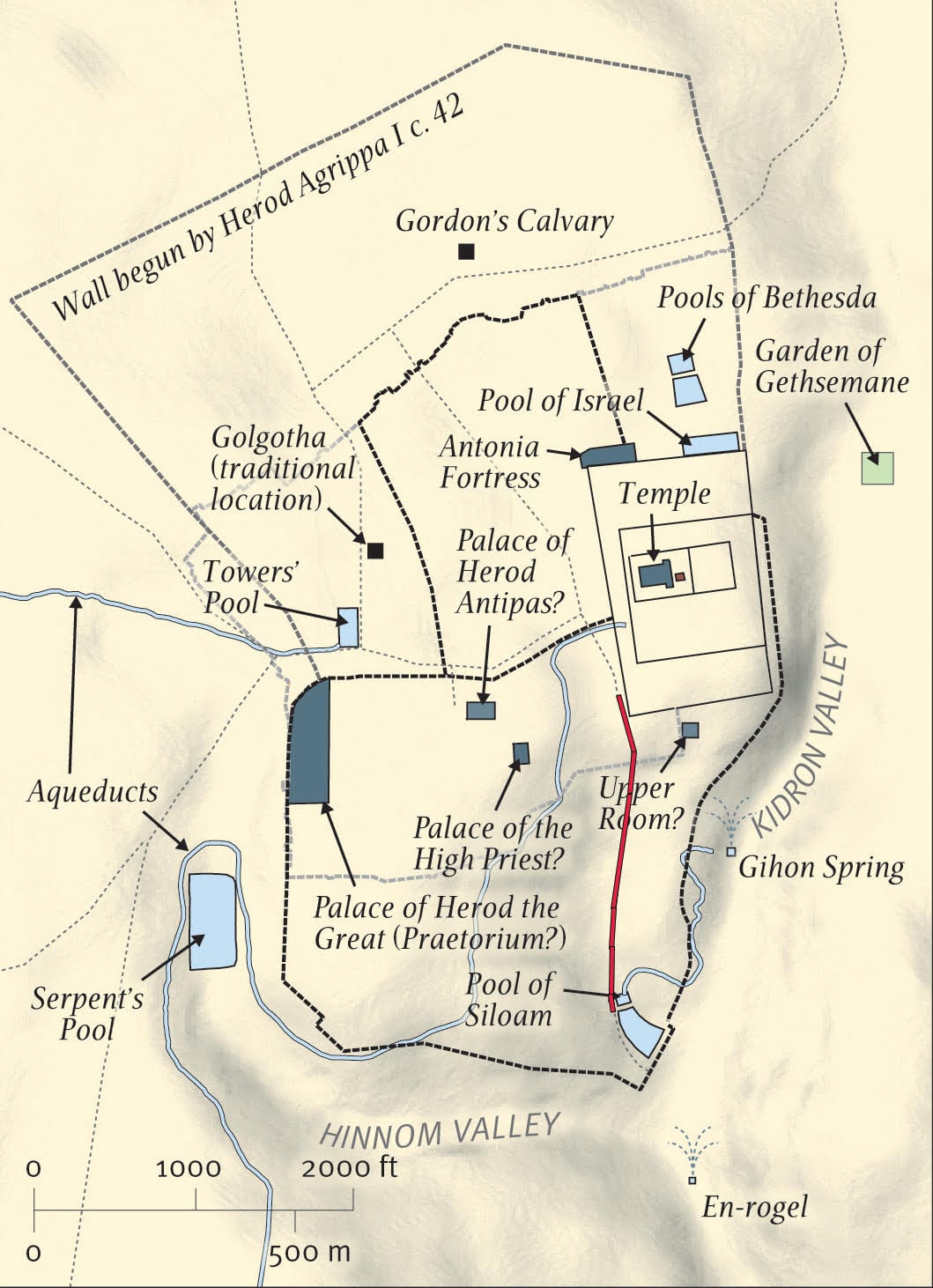

Ritmeyer marked the drawings below (from the ESV Study Bible), which show the location of the road under discussion.

These original images can be found in the ESV Study Bible and the ESV atlases.

For really helpful tools on the biblical text and archaeology, I would highly recommend the ESV Archaeology Study Bible and Barry Bietzel’s edited Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Gospels.