Author

Exodus is the second of the first five books of the OT, which are referred to collectively as either “Torah” (“law,” “instruction” in Hb.) or “Pentateuch” (“five-volumed” in Gk.). The English title “Exodus” is taken from the Septuagint and the Greek noun exodos, “a going out” or “departure,” the major event of the first half of the book, in which the Lord brings Israel out of Egypt. The Hebrew title, “Names,” is taken from the first line of the text, “These are the names of the sons of Israel who came to Egypt with Jacob” (Ex. 1:1).

The authorship and composition of the book of Exodus cannot be taken in isolation from the rest of the Torah/Pentateuch. The shape of the book of Exodus bears this out as it opens with a list of names referring to characters and events narrated in the book of Genesis (Ex. 1:1–6) and closes with an assembled tabernacle that is filled with the glory of the Lord (Ex. 40:34–38) without Israel having received full instructions for how they are to serve the Lord in it (see Lev. 1:1ff.). For further discussion of these matters in relation to what have traditionally been referred to as “the five books of Moses,” see the ESV Study Bible Introduction to the Pentateuch, pp. 35–37.

Like most books of the OT, Exodus does not explicitly refer to its authorship or composition as a book. However, its genre and content have traditionally led to the conclusion that it was written by Moses as an authoritative record both of its events and of the covenant instruction that the Lord revealed through him. While the reasons for this assessment of Exodus include the explicit references to Moses either writing (see Ex. 24:4; 34:28) or being commanded to write (see Ex. 17:14), they are not exhausted by it. The genre of Exodus is typically understood to be “historical narrative” since it presents the material as events, speeches, and covenant instructions that took place in Israel’s history. As a narrative, the book of Exodus focuses on specific aspects of the history in order to emphasize certain points for its intended audience (something that all narrative about historical events necessarily does, even if merely through what it selects as important). Exodus emphasizes throughout the book that Yahweh (the Lord; see ESV Study Bible notes on Ex. 3:14; 3:15) has remembered his covenant with Israel, will bring them out of Egypt, and will instruct them on how to live as his people as he dwells in their midst. Integral to this emphasis is the way Exodus also shows that Yahweh has chosen to reveal his purposes, lead his people out of Egypt, and instruct them on how they are to live, through Moses. Thus, while Moses probably did not write everything in the Pentateuch (e.g., the narrative of his death in Deuteronomy 34), and while there also appears to be language and references that have been updated for later readers, the book of Exodus is best read as recorded and composed primarily by Moses.

Date

The date of Israel’s exodus from Egypt is the primary chronological problem for Exodus; the book contains few clues to solve it. While the narrative refers to the cities that the people of Israel were building in Egypt (Pithom and Raamses, Ex. 1:11) and the length of their time in Egypt (430 years, Ex. 12:40), it does not include the names of any of the kings of Egypt to which it refers (nor does the book of Genesis record the name of the pharaoh “who knew Joseph”; cf. Ex. 1:8). The content of the book clearly indicates that the exodus and its time of year are important for Israel’s identity since Israel’s calendar was reoriented around the month in which they came out of Egypt (12:2), but Exodus refers to these events as if its hearers/readers were familiar with them and thus selects and shapes the details of the account in accord with its communicative purpose.

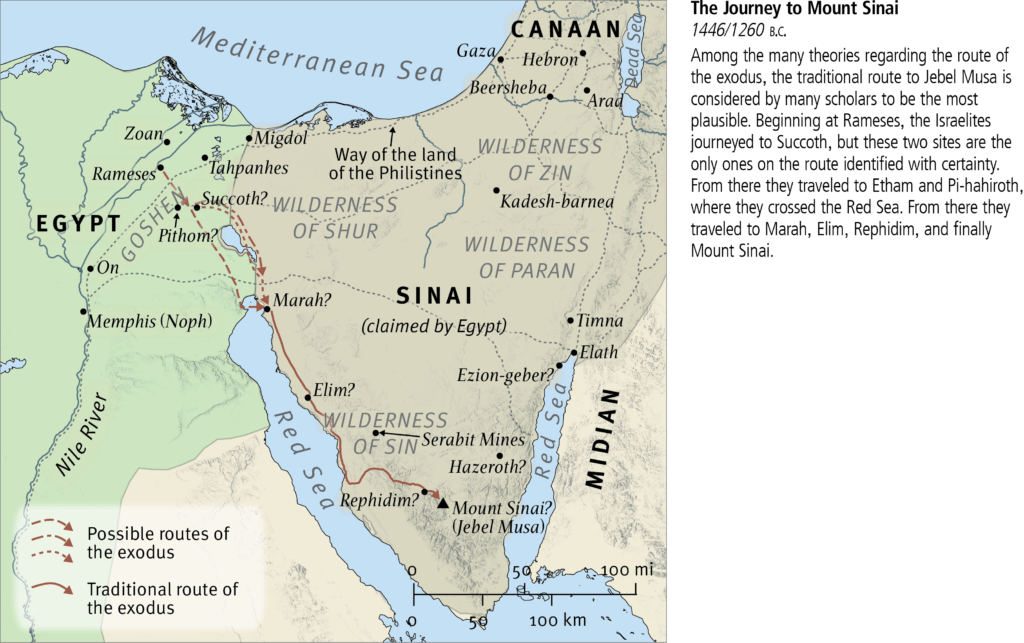

As indicated in the article on the date of the exodus (ESV Study Bible, p. 33), some scholars, working from the figure of 480 years (1 Kings 6:1) for the time since the exodus to Solomon’s fourth year (c. 966 B.C.), calculate a date of c. 1446 B.C. for Israel’s departure from Egypt. Others, because Exodus 1:11 depicts Israel working on a city called Raamses, argue that this points to the exodus occurring during the reign of Raamses II in Egypt (c. 1279–1213 B.C.), possibly around the year 1260 B.C.

Whatever the date of the exodus, the question is not necessarily about whether the numbers given in the OT are reliable but rather about trying to understand their function according to the conventions by which an author in the ancient Near Eastern context would have used them. Any attempt to determine the date of the exodus necessarily includes the interpretation of both the references in the OT and the relevant records and artifacts from surrounding nations in the ancient Near East. That is, because the OT was first given in an ancient Near Eastern setting, the interpreter’s first task is to understand, as much as possible, what an ancient Israelite would have thought the text meant. Scholars are not always sure that they can answer this question when it comes to details about dates and numbers; fortunately, the message of Exodus is plain nevertheless.

The geography of Egypt, Sinai, and the route of the exodus is another important matter for the book of Exodus that involves a similar process of trying to identify the references in the narrative to the landscape and cities with what is known or has been discovered about their location in relation to the current landscape.

Taken from the ESV® Study Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright ©2008 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.