We are pastors in Decatur, Alabama, leading churches on opposite sides of town. One of our churches was founded in 1866 by former slaves after the Civil War. The other was founded in 1965 by local business leaders during the civil rights movement. Here on the banks of the Tennessee River, Southern charm meets hi-tech, providing a home for the world’s largest space rocket factory.

And everywhere, there are reminders of the past.

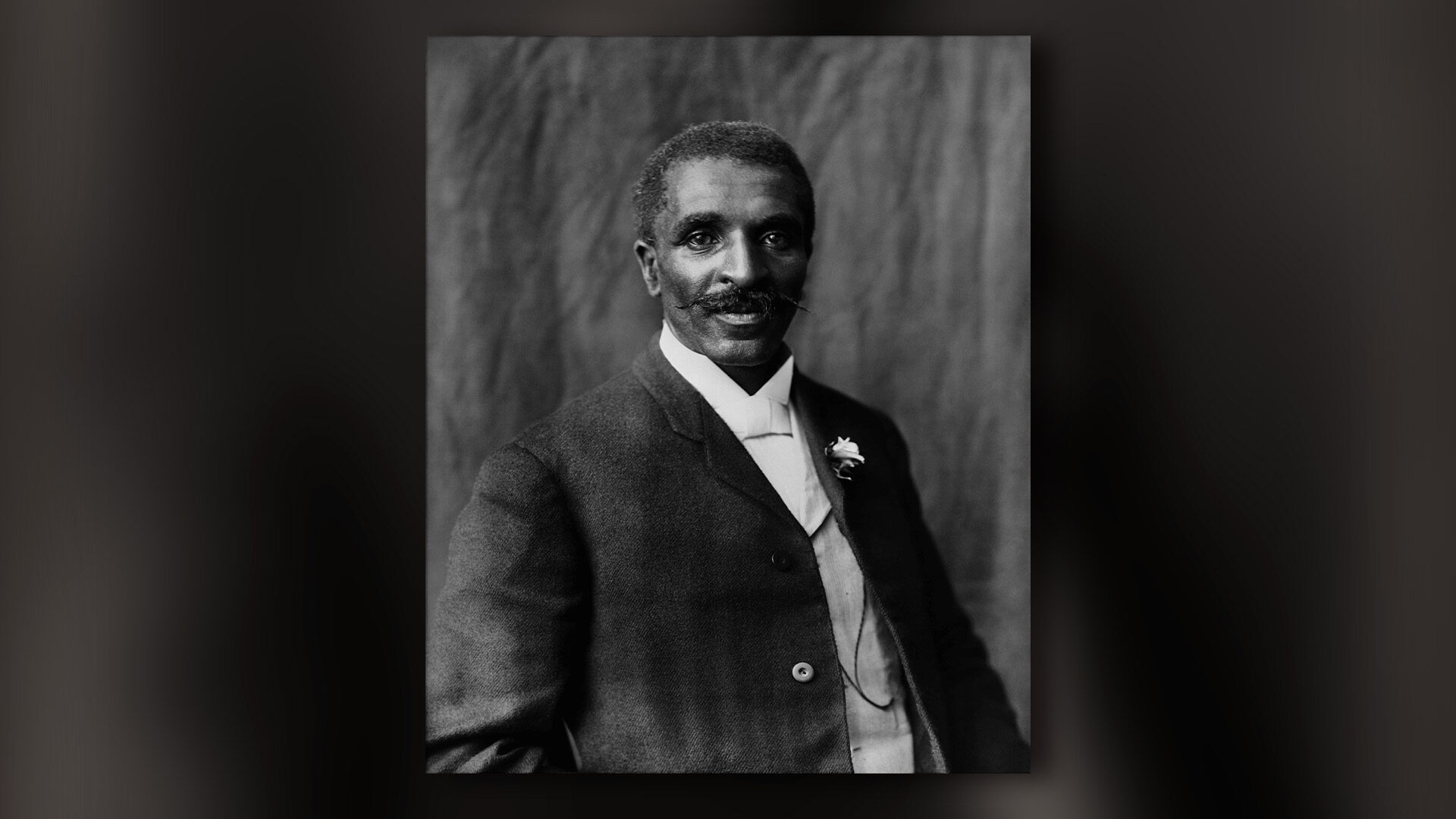

After the Civil War, city planners named five of our main streets after generals, alternating between Union and Confederate: Lee, Sherman, Jackson, Grant, Johnston. They did this to help unite Southern white residents with Northern white newcomers who migrated south during Reconstruction. On Church Street, you’ll find the site of the first school in Alabama to be named after the renowned scientist and inventor at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, George Washington Carver (1864–1943).

In 1935, Carver visited our city for the renaming of the Carver Elementary School; he spoke to a thousand-member integrated audience in a segregated theater. He would’ve passed near the Morgan County Courthouse, where two years earlier the infamous “Scottsboro Boys” retrials began. Nine African American youths were falsely accused of rape and convicted by an all-white jury. Their retrial yielded one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in civil rights history—ruling that blacks could not be systematically excluded from juries. This is the world Carver navigated that June day in 1935.

White Christians and Carver (Steve)

As a white pastor in the Deep South, I’m helped in three ways by studying Carver’s life.

1. Carver helps me convey the historic harmony of Christianity and science.

I serve a church filled with people who make their livings with science––engineers, astrophysicists, chemists, educators, physicians, pharmacists, biologists––and who seek to harmonize their study of God’s world and God’s Word. Carver illustrates a point I often make as their pastor: there’s no final conflict between good theology and good science.

There’s no final conflict between good theology and good science.

Carver explained to a New York audience that in experiments he needed “God to draw aside the curtain.” When a reporter criticized the speech, Carver wrote to a friend that the criticism was really directed “at the religion of Jesus Christ.” He continued, “Dear Brother, I know that my Redeemer liveth. . . . Pray for me that everything said and done will be to his glory. I am not interested in science or anything else that leaves God out of it.”

2. Carver alerts me to black American contributions to our national prosperity.

Carver was renowned for achievements in the laboratory, and what happens in laboratories has real-world consequences. With science, Carver equipped black sharecroppers to increase profits and escape enslaving debt to white landowners. Today, one way to address the economic disparity between white and black households is to empower black students for careers in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). These are among the professions in which black Americans are least represented. Carver offers an example to follow.

3. Carver instructs me in the complexity of black history.

I once naively viewed the black church as monolithic in its historic effort to secure justice. But Carver represents one strategy among several in the struggle for civil rights. By practicing Christian ethics “with patience and deference,” he hoped black Americans could gradually convince white Americans to view them as equals and as essential to the nation’s common good.

Carver’s gradualism posed no threat to the social order of the church-laden South. He absorbed the humiliation of Jim Crow segregation. His research at Tuskegee was considerably underfunded compared to white land-grant schools, so he relied on Northern philanthropists like Henry Ford. He avoided politics, protests, and white women while training black farmers who worked the cotton-exhausted soil of the South. For many white Christians, Carver was a good example, and a useful token, of a black man helping his race but keeping his place.

I’m humbled not only by Carver’s endurance in suffering but also by the rich nuance and tragic turns of black history.

Black Christians and Carver (Daylan)

I’m a black pastor born and raised in the Deep South, so Carver isn’t an obscure historical figure to me.

1. Carver was a real person who affected real people.

When Carver visited our city in 1935, my church’s oldest member was there. Etta Freeman, now 105, was in high school. Carver touched the lives of people I know personally, and his views on civil rights illustrate the tension black Christians feel in the struggle against racism.

In the Atlanta Compromise of 1895, Booker T. Washington, Carver’s boss at Tuskegee, outlined what he thought was the best course for black people: accept social segregation and focus on vocational education, using agricultural and industrial skills acquired in slavery. Washington’s voice, however, was challenged. To leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois, black progress required higher education, political reformation, and broader social consciousness. Carver aligned more closely with Washington.

I’ve wrestled to make peace between the viewpoints of Washington and Du Bois. I haven’t come to my conclusions easily, but I realize our understanding of Carver must be shaped by an awareness of his faith and context.

2. Carver’s faith informed his perspective.

Like other black leaders of his day, Carver was a committed Christian. Du Bois’s Christian convictions are less clear. To some, Du Bois had a more compelling political synthesis and represented a better path forward. But his framework was philosophically—rather than theologically—informed. Carver viewed his own work as a service to humanity motivated by his love for Christ. As David Chappell has shown, the appeal to Scripture by leaders like Carver laid the foundation for the success of the civil rights movement.

3. Carver represents a generation of black Christians struggling for survival.

For a long time, I was discontent with what I thought was Carver’s neglect of social consciousness. What Martin Luther King Jr. called the “tranquilizing drug of gradualism” yielded a societal stupor that ruined the lives of countless people made in God’s image. But in time, I came to better understand Carver’s situation. Though various forces conspired to destroy him, they failed to compromise his work, his understanding of his worth, or the importance of his faith.

In 1935, being black in the South was dangerous, particularly for a public figure. My grandmother’s wisdom informed my perspective. In my youth, she’d often say to me, as only grandmothers can do, “I worry about you because they know you’re smart. It’s our smartest ones that have the hardest time.” What may appear to us like accommodation was, in all likelihood, a strategy for survival during Carver’s life.

Reminders Everywhere

Giving serious attention to the complicated history of real people like Carver provides a starting point for the conversations that must continue between black and white believers. There’s no way to understand the present without understanding the past.

Though various forces conspired to destroy him, they failed to compromise his work, his understanding of his worth, or the importance of his faith.

In conversations about race, the tension remains for many black Christians: when to speak and when to be silent. Many are tired of explaining racism to white Christians and showing that legal victories may have removed segregation from our laws but not from our hearts. Some have lost hope of conveying how past injustices have present consequences. Sometimes the frustration erupts in anticapitalist protest in the tradition of Du Bois. Other times, it’s easier to retreat to the safer seclusion modeled by George Washington Carver in Tuskegee.

Many white Christians are weary of a cancel culture that summarily dismisses their historical heroes. They’re offended when judged by their skin color or when alleged racism is used to excuse immoral behavior. Sometimes the frustration manifests in a belligerent “anti-wokeness.” Other times, it’s easier to retreat to white neighborhoods and social circles, remaining voluntarily unaware of the difficulties dealt to many of their black brothers and sisters. Resisting the trend to see racism everywhere, they may be inclined to see racism nowhere.

Our city’s schools have been integrated for decades, and African Americans serve on juries at the Morgan County Courthouse. But it’s still the case that “11:00 on Sunday morning is one of the most segregated hours” in our city—like most cities in America, not just in the South.

And everywhere, there are reminders of the past.

Yet our common allegiance to the risen Christ, mutual love of history, and honest conversations feed our optimism that this long process is moving toward the inevitable reconciliation guaranteed by the gospel, which makes us “one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28). We have a long way to go, but we’ve come a long way so far.