If Christianity is true, why do so many Christians act in horrific, un-Christlike ways? Why has Christian history been so consistently tarnished with war, violence, and oppression? Why should one believe Jesus is God if so much evil has been done in his name?

These questions represent one of the most popular objections to Christianity today. They are good questions: questions Christians should take seriously and know how to answer; questions that should chasten us and cause us to commit to living in ways that don’t besmirch the name of Jesus.

Thankfully, an excellent new documentary, For the Love of God: How the Church Is Better and Worse than You Ever Imagined, features Christians honestly and soberly considering these questions.

Christian History: The Horror

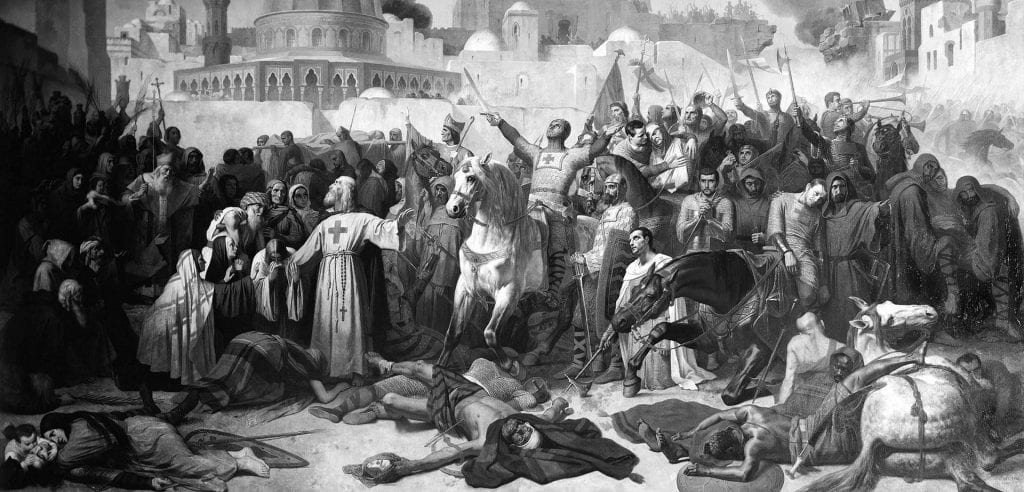

A production of the Center for Public Christianity (CPX), an Australian Christian nonprofit devoted to using media to enhance the public understanding of Christian faith, the documentary is hosted by John Dickson (CPX founding director), Simon Smart (CPX executive director), and Justine Toh (CPX senior research fellow). It opens in Jerusalem with a description of one of the many atrocities of the Crusades, and for the next 90 minutes it does not shy away from the ugly episodes of Christian history.

The film crisscrosses the globe, recounting various dark episodes in Christian history. In Belfast, for example, Smart ponders the religious violence that occurred in Northern Ireland over three decades. “How do people who claim a religious faith reconcile what happened here with what they believe?” he asks.

John Lennox, who grew up in Northern Ireland during the Troubles and whose family’s store was bombed for employing both Protestants and Catholics, is interviewed in the film.

“I’m utterly ashamed of it,” he says. “I’m ashamed that the name of Christ has even been associated with a bomb or an AK-47. For the simple reason that people who do that are not following Christ. They are disobeying him.”

Shame indeed. So many horrors have been committed by people who claim the name—and even more troublingly, the cause—of Christ: wars, slavery, colonial oppression, the subjugation of women, segregationist policies, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and on and on. How do we reckon with all this? For the Love of God leans into this question.

Christian History: The Heroic

But just as the documentary doesn’t shy away from the evils done by so-called Christians in history, neither does it shy away from celebrating the many ways Christian influence has shaped the world positively.

The film notes how ideas taken for granted in today’s world—universal human rights, the innate dignity of persons regardless of their utility, or even that humility is a desirable quality—came from Christianity. The arrival of Christianity and its theology of imago Dei revolutionized the way vulnerable populations fared in the Greco-Roman world, where barbaric practices like infant exposure were normal and equality between the sexes was a foreign concept.

The film shows how Christ’s teachings to love your enemy (Matt. 5:44) and turn the other cheek (Matt. 5:38–40) inspired the nonviolent resistance of Martin Luther King Jr., while the Parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:25–37 (among other teachings) inspired a humanitarian emphasis that has characterized Christianity throughout its history. From early Christians in Rome caring for the sick and dying (not just their own, but everyone) to Mother Teresa and modern-day Good Samaritans like Kent Brantley, Nancy Writebol, and Rick Sacra, followers of Jesus have constantly been inspired to enter harm’s way to care for the vulnerable.

Throughout Christian history, followers of Jesus have constantly been inspired to enter harm’s way to care for the vulnerable.

Though at times the “good Christian” examples are a bit too predictable (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King Jr.), the documentary does shine the light on lesser-known heroes. I enjoyed learning about Father Damien of Molokai, who gave his life to serving a leper colony in Hawaii, and the Serampore Trio of English missionaries (including William Carey) whose impact in India included launching a college and succeeding in efforts to outlaw infanticide and the killing of widows through the practice called sati.

There are countless other examples, of course. A film of this topic really could (should!) be a multi-season, long Netflix documentary (For the Love of God does have a longer version of four one-hour episodes). But with limited time, this film does a good job selecting illustrative examples and moving the narrative along at a concise clip.

Tuning Our Song to Jesus

As documentaries go, For the Love of God is well-produced and compelling. It features a who’s who of historians, philosophers, and theologians weighing in on the good and bad of church history—scholars like David Bentley Hart, Lynn Cohick, William Cavanaugh, Miroslav Volf, Rodney Stark, and Christopher Tyerman, among many others. Some are more generous than others as to how Christianity comes off in the final analysis, but none is utterly damning in their critique. This is one area where the film could have been even stronger, perhaps: a willingness to give voice to truly stinging, well-articulated critiques of Christianity and its oft-ugly legacy. If Christians are to winsomely answer these arguments, we need films like this to engage them, presenting the strongest version (not the easily refutable version) of the anti-Christian critique.

What is the best answer to these critiques? This documentary uses a helpful musical metaphor to suggest a possible response.

“It’s easy to dismiss the religion of Jesus Christ on account of the many sins of his followers,” Smart says in the film. “But perhaps it’s too easy, like judging a piece of music on the basis of a bad performance.”

As we watch a cellist performing Bach, Smart continues: “A bad delivery doesn’t diminish the genius of the original composition.”

A bad delivery doesn’t diminish the genius of the original composition.

How consistently have Christians played the melody of Jesus, the new tune he gave the world? It’s an open question—a convicting question the film carefully engages.

“When Christians have played out of tune with Jesus,” Toh observes, “the results have been disastrous.”

Indeed. The dissonance of Christians living “out of tune” with Jesus has often sounded like nails on a chalkboard to the world—repulsive noise that attracts no one to the gospel. But when Christians have played the tune well, in harmony with Jesus, the song has been beautiful—an attractive symphony that can soften hearts to the gospel.

Are we playing in tune with Jesus, or are we hijacking his melodies to riff in our own way? For the Love of God challenges us to consider this question. For the love of God, and for the love of his world, may our lives sing a Jesus song.