Through Scripture, we see the goodness of God in his extravagant will to give. As the curtain opens on creation, his first command is not prohibition but invitation: “Be fruitful and multiply.” When the people of Israel are poised to enter the Promised Land, Moses sets before them the alternatives of “life and good, death and evil,” and reprises God’s creation invitation: “Live and multiply and the LORD your God will bless you in the land that you are entering” (Deut. 30:16). The gospel itself climaxes in God’s giving: “For God so loved the world that he gave.”

But with the cross at the center of Christianity, critics have suggested that God opposes our flourishing—that obedience is not a means to the good life but rather a form of masochism. As Jesus himself said, in the kingdom of God the only way to save one’s life is to lose it first.

Cruel and Unnecessary Asceticism?

For modern secularists, there is the sense that Christianity has made exaggerated moral demands, which “cannot but end up mutilating us; it leads us to despise and neglect the ordinary fulfillment and happiness which is within our reach” (Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, 623–624). It asks us to despise our families (Luke 14:26); it commends heavenly treasure over earthly accumulation (Matt. 6:19); it forbids sexual license (Heb. 13:4). According to the critique, Christianity imposes a cruel and unnecessary asceticism, forcing us to repress desire and offending the primacy of individual freedom, the heartbeat of modern exclusive humanism.

It is not simply that Christianity is an alternate ethic in the secular age; it is an enemy.

“In recent centuries, and especially the last one, countless people have thrown off what has been presented to them as the demands of religions, and have seen themselves as rediscovering the value of the ordinary human satisfactions that these demands forbade. They had the sense of coming back to a forgotten good, a treasure buried in everyday life” (Taylor, A Secular Age, 627). In other words, humanity flourishes by throwing off the deadening constraints of religion and following the whims of their desires—wherever those desires might lead.

To illustrate this point, Taylor talks about French writer André Gide’s coming out in the 1920s. It was a “move in which desire, morality and a sense of integrity came together. . . . It is not just that Gide no longer feels the need to maintain a false front; it is that after a long struggle he sees this front as a wrong that he is inflicting on himself, and on others who labor under similar disguises” (475). Seen from the value-laden perspective of the secular age, Gide does not abandon moral commitments so much as take them up, courageously choosing to live as his most authentic self. Gide is one of many to declare his only binding moral demand to be, “Find yourself, realize yourself, release your true self” (475). His (and ours) is an Age of Authenticity, wherein there are no rules to keep except the dictates of personal desire.

As one popular author—a self-proclaimed follower of Jesus—baldly put it when defending a new lesbian relationship, “The most revolutionary thing a woman can do is not explain herself.”

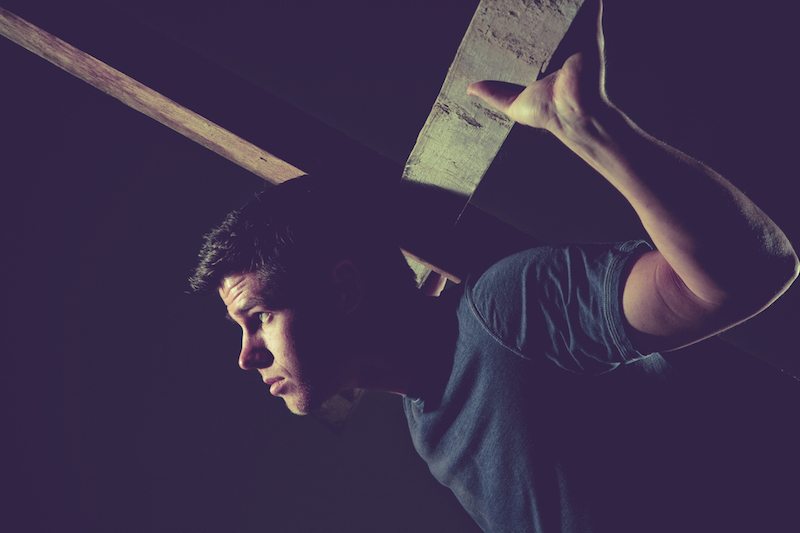

Cruciform Life

How can we give ourselves fully to earth and heaven at the same time? Sure, personal fulfillment and piety may be compatible, but as Taylor observes, “The tension between fulfillment and dedication to God is still very much unresolved in our lives” (Taylor, 656). In the Middle Ages, the solution for resolving this tension was a division of labor: the kingdom of heaven was furthered in the celibate vocations, the kingdom of earth by everyone else. But insofar as the Reformation abolished the sacred/secular divide, it did not fundamentally resolve the tension.

“For the ordinary householder this answer seems to require something paradoxical: living in all the practices and institutions of flourishing, but at the same time not fully in them. Being in them but not of them; being in them, but yet at a distance, ready to lose them” (Taylor, 81).

How can we, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer described in a letter to his fiancée, say yes to God and yes to God’s earth?

We can’t ignore Calvary at the center of our story, an irrefutable symbol of self-sacrifice. The cross is not just a “merely regrettable byproduct of a valuable career of teaching,” and it will always challenge our instinctive ideas about flourishing (Taylor, 651). On the one hand, Taylor assures readers that Jesus’s agony at the moment of his death upholds the dignity of bodily life. “It is precisely because human life is so valuable, part of the plan of God for us, that giving it up has the significance of a supreme act of love” (644). On the other, even bodily life is something we should willing to lose at any moment.

Perhaps, as my pastor has suggested, we might imagine the life of faith standing on the knife edge of the Lord’s Prayer salutation: Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. God is a good Father, and as Calvin wrote, this “frees us from all mistrust.” But he is also holy. There’s inscrutability to his ways, and he does what pleases him. Should we not marvel that what has stunningly pleased God is his own suffering and degradation, the emptying of himself in order to fill salvation’s cup?

Obedient Love, Not Autonomous Freedom

So what does it mean to imitate that self-sacrificing love?

For one, when Jesus took on his cross, he laid down “fullness”—and it is a sobering example that God has never signed his name to our promissory notes of marriage, children, financial security, meaningful work, and health. If the empty tomb is the sign of a new creation, the cross is the sign of a broken one. “Now that there is a tension between fulfillment and piety should not surprise us in a world distorted by sin, that is, separation from God” (Taylor, 645). Let’s not forget that we’re still in the middle act of the drama, groaning for God to finally and fully repair this world, which can’t help but disappoint. No one gets his best life now. As Elisabeth Eliot writes in her book A Path Through Suffering, “Does our faith rest in having our prayers answered as we think they should be answered, or does it rest on that mighty love that went down into death for us? We can’t really tell where it rests, can we, until we’re in real trouble” (65).

Further, when Jesus took up his cross, he laid down, in a mysterious way, his freedom. To be clear, the author of Hebrews insists Jesus did not go to the cross against his own will: “Behold, I have come to do your will, O God” (10:7). And yet we have the scene of a kneeling, weeping, pleading Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane where, in a dramatic reversal of humanity’s first act of self-sovereignty, God refused autonomy and chose surrender instead, emptying himself of prerogative and “becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:8). Our ethic is not autonomous freedom, but obedient love. “One central constituent of Christian revelation is that God not only wills our good, a good which includes human flourishing, but was willing to go to extraordinary lengths to ensure this, in the becoming human and the suffering of his son” (Taylor, 649).

Like Jesus, we are free to deprive ourselves so another might flourish.

Alleluia

The Lord’s Prayer teaches us to pray for God’s kingdom to come; it also teaches us to pray for daily bread. For all the tension pent up in those seemingly disparate petitions, perhaps Bonhoeffer resolves it best in a letter to his friend, Eberhard Bethge: “God, the Eternal, wants to be loved with our whole heart, not to the detriment of earthly love or to diminish it, but as a sort of cantus firmus”—the fixed melody line in a polyphonic composition.

In other words, we say yes to God’s earth—but never to the detriment of alleluia.

Editors’ note: This is an excerpt from TGC’s newly released book, Our Secular Age: Ten Years of Reading and Applying Charles Taylor, now available at Amazon (Kindle | Paperback) and WTS Books. You can also listen to Michel’s interview with editor Collin Hansen in this podcast.