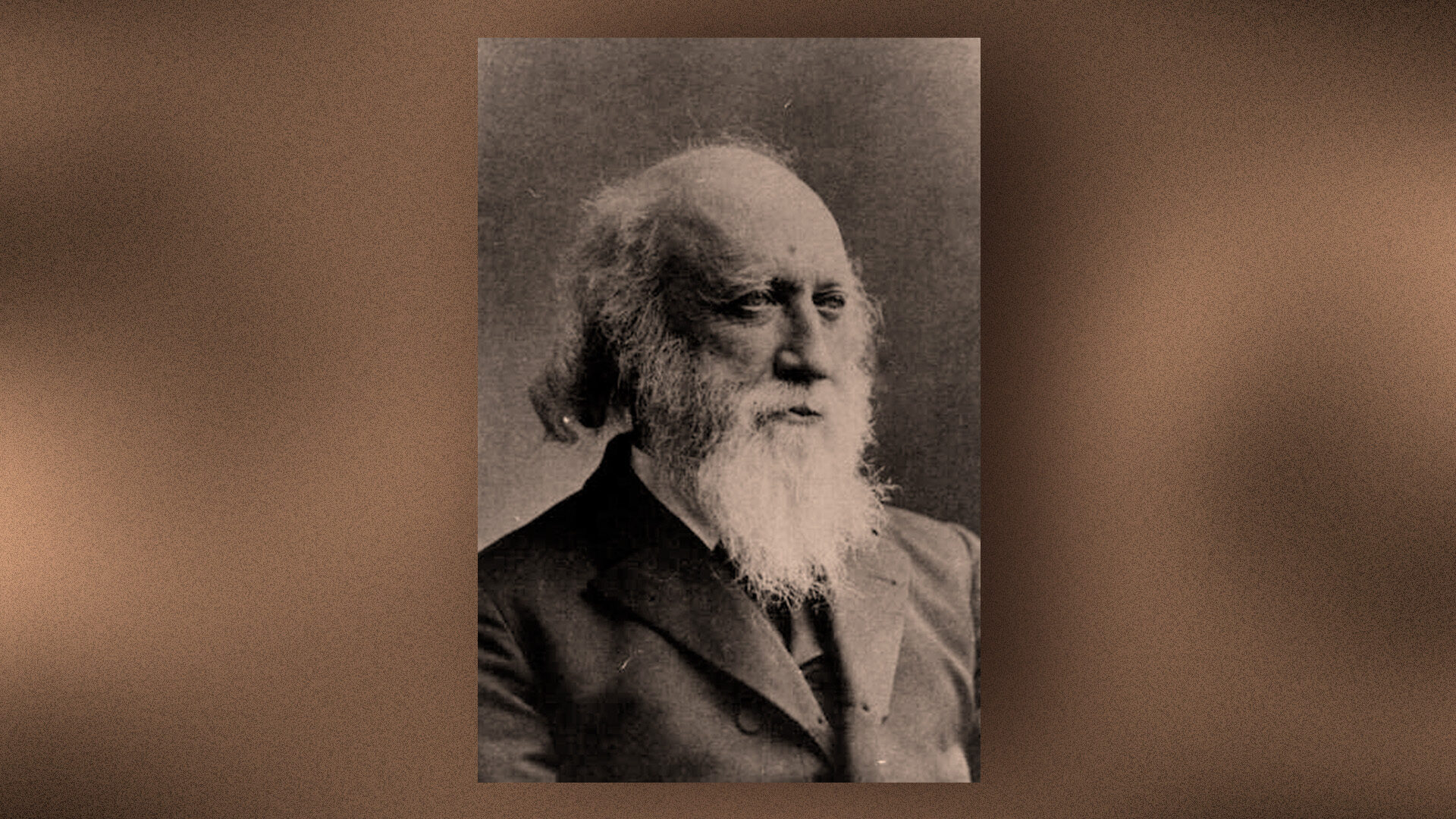

In a family of pastors, Charles Beecher (1815–1900) was the black sheep.

Stubborn and quick-witted, he was remarkably like his father, Lyman Beecher, one of the most famous preachers of the Second Great Awakening. However, much to his father’s disappointment, Charles was not interested in preaching. His love was music, not ministry. Nor was Charles interested in Calvinism, or at least his father’s version of it. One night, around the dinner table, Charles and Lyman engaged in a shouting match over Jonathan Edwards’s Freedom of the Will.

Known for mood swings, Charles wasn’t the first or the last of Lyman’s sons to rebel against authority. His older brother George had been suspended from college and his younger brother James would be too. But Charles was the first to challenge his father, the “Great Gun of Calvinism.” Lyman Beecher had 7 sons, all of whom he expected to become ministers: William, Edward, George, Henry, Charles, Thomas, and James. By 1838, all four of Charles’s older brothers had begun pastoring churches. But Charles didn’t look like pastor material. He wanted to escape the Puritan authority of his father. So he did . . . to New Orleans.

Runaway

When the 22-year-old left Cincinnati on a steamboat for New Orleans to work as a clerk at a wholesale house, it was obvious he was running away from an overbearing father. While serving as a church organist in New Orleans, Charles was working out his relationship to organized religion and to his deeply religious family. He was also experiencing the world. In his letters to his sister Harriet, he described the slave plantations of the Deep South, providing valuable material his sister would later use in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

However, Charles was also in tremendous pain. When he published a poem in a New Orleans paper that questioned the eternal state of his deceased mother and lamented that he had no more close friends, his brother Henry showed Lyman the newspaper clipping. The poem read,

Oh, must I live a lonely one,

Unloved upon the thronged earth,

Without a home beneath the sun,

Far from the land that gave me birth?

Alone—alone I wander on,

An exile in a dreary land;

The friends that knew me once are gone;

Not one is left of all their band.

I look upon the boiling tide

Of traffic fierce, that ebbs and flows,

With chill disgust and shrinking pride,

That heartfelt misery only knows.

Where is the buoyancy of youth,

The high, indomitable will,

The vision keen, the thirst for truth,

The passions wild, unearthly thrill?

Oh, where are all the bounding hopes

And visions bright, that were my own

When Fancy at her will could ope

The golden doors to Beauty’s throne?

My mother! whither art thou fled?

Seest thou these tears that for thee flow?

Or, in the realms of shadowy dead,

Knowest thou no more of mortal woe?

In that still realm of twilight gloom

Hast thou reserved no place for me?

Haste—haste, oh mother, give me room;

I come—I come at length to thee!

Pleading for his mother, Charles Beecher felt trapped. He could find no comfort in life or in death. He had no help from “friends” on earth and no assurance of salvation. Charles had run away from his family and their faith and, by extension, from the hope of the resurrection and his mother. The poem was thus a judgment upon his controlling father and a cry for help.

Loving Plea

Charles had run away from his family and their faith and, by extension, from the hope of the resurrection and his mother.

Lyman Beecher wasn’t known for brushing doctrine aside. He had almost broken off an engagement with Charles’s mother, Roxana, in the 1790s over a theological disagreement. He had also pushed his oldest daughter, Catharine, away from evangelicalism when he desperately pressed for her conversion following the death of her fiancé.

However, Lyman had softened a bit. On this occasion, he didn’t respond with his characteristic burst of theological argumentation. He didn’t preach a sermon to his son about the doctrines of heaven and hell and the immortality of the soul. Instead, the college president chose a less professorial approach to parenting. In one of the most heartfelt and compassionate letters he ever penned, Lyman Beecher wrote to his son to remind him of “the trembling solicitude of a father’s love.”

Lyman insisted Charles would always be loved—no matter what he believed. Although their “opinions may differ,” he wrote, their time apart had only produced “a more intense interest, solicitude, and sympathy” for him. His father missed him. But Lyman wouldn’t interfere in Charles’s personal affairs. Expressing a deep sadness for Charles’s pain, Lyman only wanted him to know that he dreamed of his “returning home.”

Nevertheless, for Lyman Beecher, no conversation was devoid of some biblical allusion, comparing Charles to the one lost sheep of Luke 15. Although this was a bit on the nose for a son grappling with spiritual doubt and resentment, given the circumstances, the analogy wasn’t entirely inaccurate. Of all the Beecher children, Charles was the first to literally run away from his father.

A more appropriate metaphor for Lyman’s relationship to Charles would have been the parable of the prodigal son in the very same chapter of Luke. In fact, this parable was almost certainly on Lyman’s mind when he pleaded with Charles not to abandon his faith and his family. Charles had fled his father’s house, but the father was still waiting expectantly for his return: “Oh, my dear Charles—the last child of my angel wife, your blessed mother—you can never know the place you fill in your father’s heart, and the daily solicitude and prayers of his soul for your protection and restoration to equanimity, satisfaction, and joy of heart in communion with God.”

Ultimately, Lyman saw Charles’s departure as a crisis of faith and he wanted him to know the entire Beecher clan was there for him. “Whenever the temptation comes over you to feel that you are friendless,” he charged, “remember . . . that your father lives, that Aunt Esther lives almost only to suffer and pray for you, and that every one of your brothers and sisters are united in a weekly concert of prayer for your preservation and restoration to joy and peace in believing.”

Indeed, when she was alive, Roxana had prayed for her son’s salvation, he reminded Charles. Alluding to Augustine’s Confessions, Lyman compared Roxana to Monica, Augustine’s mother, who prayed incessantly for her skeptical son. Lyman’s message to Charles was the same as the Bishop of Hippo’s to Monica: “The child of so many prayers can not be lost!” (Lyman was enlisting the help of Scripture and the early church.) If Roxana could speak, he wrote, she would certainly point Charles’s “troubled soul” to Christ. Lyman then preached the gospel to his son, quoting Matthew 11:28: “Come unto me, thou weary and heavy laden, and I will give thee rest.”

Prodigal

Not long after Lyman penned his letter to Charles, his son found rest from his burdens and came back to the fold of God. He later confessed he had “made shipwreck of the faith.”

Lyman compared Roxana to Monica, Augustine’s mother, who prayed incessantly for her skeptical son.

Upon returning to Cincinnati, Charles was married in 1840 to Sarah Coffin. After serving as his brother Henry’s worship pastor in Indianapolis, he became a “missionary to the West” and served as pastor in Fort Wayne, Indiana, from 1844 to 1850. He also composed hymns and published several books and sermons, including The Duty of Disobedience to Wicked Laws: A Sermon on the Fugitive Slave Law (1851). Indeed, all seven of Lyman’s sons would become pastors—even Charles.

He and his father never saw eye to eye on many doctrines, and Charles would struggle for the rest of his life with “systematic” theology. However, Charles maintained that much of his aversion to his father’s Calvinism was simply due to his father’s “well-known admiration of President Edwards,” rather than Edwards’s theology itself.

As an older man, Charles attributed his homecoming to his father’s persistence and prayer. Indeed, he confessed, Lyman had done “all that could be done” for his son in that critical hour. He would never again question his father’s love. Charles recorded he was “restored through the mercy of a covenant-keeping God.” He relayed this story in his father’s autobiography, a work composed chiefly by his formerly prodigal son.