Kenosha Christian Academy was supposed to be a church plant.

“Throughout seminary, I had a growing desire to do ministry in a hard place,” said Justin Denney. After finishing his MDiv at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (TEDS), he came on staff at Crossway Community Church in Bristol, Wisconsin, as a church planting resident in 2018.

Crossway knew exactly where they wanted him to go—into the Wilson neighborhood of nearby Kenosha, where they’d been running an after-school program for the past eight years.

Kenosha sits on Lake Michigan, in the urban sprawl that nearly connects Chicago and Milwaukee. With a population of about 100,000, Kenosha’s median household income is about $60,000 a year. Around 15 percent of the people live below the poverty line.

A year after Denney moved his family into the neighborhood, Jacob Blake was shot by police less than a mile from his house.

“That set the city on fire,” Denney said. “It happened on a Sunday. On Monday night, there were sirens the whole night. In the poorest, most densely African American neighborhood in the city, the whole strip burned. It was a really dark time.”

The next day, a friend texted him an article from The Gospel Coalition on the riots in John Piper’s neighborhood in Minneapolis, near where George Floyd had been killed.

“I cried my way through it,” Denney said. He loved the example of long, steady faithfulness in a hard place. But what caught his heart most wasn’t Bethlehem Baptist Church. It was Hope Academy—the classical Christian school that Bethlehem member Russ Gregg started in 2000 to better love his neighbors.

The reason for Denney’s pivot? The Wilson neighborhood already had historic, black, gospel-preaching churches—it didn’t need another one. Instead, Denney found that the children in his after-school program needed “long-term relationships with people who loved them and, as they got down the road, network connections,” he said.

He couldn’t think of a better way to do that than a classical Christian school. But the barriers seemed impossible until he saw Gregg do it.

Last fall, just over 50 students walked into the brand-new Kenosha Christian Academy (KCA) for the first time. For the past six months, Denney has watched his students’ hearts soften and awaken. He can see glimmers of a different future for them.

“I’m so grateful for all the different things God has put in place to make it possible,” Denney said. “I just see this as an unparalleled mission opportunity to address the challenges of generational poverty with evangelism and discipleship.”

Neighborhood Schools

It wasn’t that Denney’s neighborhood didn’t have its own schools—it had two. But less than 10 percent of students at both schools are proficient in math and reading, according to the state of Wisconsin. One ranks in the bottom 3 percent of schools in the state. And in January, school officials voted to close the other.

Many teachers and administrators work hard and care deeply about their students, Denney said. But the system’s negative effects—particularly on low-income students—demonstrate its brokenness.

“We’d work with kids who could barely read in fifth grade,” he said. “Even the really sharp and driven kids were receiving a subpar education. Their imaginations were almost completely unengaged. They thought school was boring, and they didn’t want to work hard.”

Even the really sharp and driven kids were receiving a subpar education. Their imaginations were almost completely unengaged. They thought school was boring, and they didn’t want to work hard.

Even more concerning was the “moral, spiritual, and cultural side,” Denney said. “James Davison Hunter talks about how public education has created an environment where character is impossible. Even though there are a lot of character programs, the underlying assumptions about identity and the human person encourage kids to seek what is best for themselves.”

In a culture where kids are seldom encouraged to do anything against their immediate wishes, “you can’t form character,” Denney said. “And that leaves kids exposed to the winds of pop culture because it doesn’t give them anything firm to latch on to.”

Even so, starting a whole new school is a lot of work. Wouldn’t it be easier to join the existing school system and work for reform from the inside?

Trouble on the Inside

Megan Heinrich was ready to try.

Homeschooled until college, she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Parkside, which is in Kenosha. She majored in elementary education, attended Crossway, and started helping in the same after-school program as Denney.

“I wanted to dive into public education—I thought I could change the world,” she said. “I believe education and literacy are foundational to kids’ success. I felt like if I could build trust with families, I could share the gospel—or at least model grace.”

As soon as she graduated, she got a job teaching fifth grade in Denney’s neighborhood. She expected the work to be hard but rewarding. What she didn’t expect was the consistent, disruptive violence.

“Kids were out of control,” she said. “I would regularly break up fights or evacuate my room while trying to get scissors away from somebody. . . . I’d have students who could derail my classroom—by throwing objects, filming on their cellphone, or threatening people—but they’d never be removed.”

In fact, they’d rarely be addressed, since “other classrooms were experiencing more chaos” than Heinrich’s was. In the five years before she came, her school went through eight principals in five years.

Three years in, Heinrich was ready to quit.

“I did not feel fruitful at all,” she said. “I didn’t have any sense of even being able to help the kids to read.” On top of that, she wasn’t building relationships. She didn’t know the parents, and the relationships inside the classroom were unstable and chaotic.

“You can’t build a community of students if some are literally threatening to shoot up the others’ houses that afternoon,” she said. “You just can’t do that.”

So when Denney threw out the idea of starting a classical Christian school, Heinrich knew he was too idealistic. “I could not wrap my head around it,” she said. In an area where education was often synonymous with free childcare, “who is going to want that?”

Will Anyone Come?

Jerrell Griffin was 15 years old when he first went to jail for drugs. Over the next 12 years, he spent more months in jail than out. He believed in God and prayed for help. But it always seemed like just a few months before he was hanging around the wrong crowd again, selling drugs, and then heading back into prison.

“I was on my bunk one day when the cell doors popped open unexpectedly, which means it’s time to fight,” he said. Griffin hopped off his bunk and backed into the corner with his hands up. But the inmate who walked in didn’t rush him. He just looked at Griffin and asked if he could help him.

“Who are you?” Griffin asked.

“I’m your daddy,” the man said. And he was.

“It was weird and scary,” Griffin said, partly because it’s a crazy coincidence to be locked up with your father, and partly because it made Griffin’s own trajectory clear. He knew he didn’t want to be serving a 20-year sentence like his father. Around the same time, he met a girl who believed in God and went to church.

“When I met Shayna, she gave me meaning—she gave me something to look forward to,” he said. He knew he could have a different life with her—they could go to church, build a family, and have a stable home.

“I was reading the Bible like crazy, so when I got out, she and I were on the same page,” he said. It was a good page—Griffin married Shayna, went to school, and opened his own barbershop.

The couple met Denney while having dinner with mutual friends. Denney told them he wanted to start a Christian school, with Christian curriculum and Christian teachers.

“I was like, Man, this sounds like a really good opportunity for our son,” Griffin said. He knew he wanted more for his boy Eli than he’d had.

Shayna was thinking the same thing. Eli was in first grade at a charter school but was struggling and didn’t like it. She loved the idea of a curriculum that connected every subject to Christian principles, of teachers and classmates who were more likely to influence him toward truth, goodness, and beauty than toward drugs, violence, and gangs.

Jaran Bouie also loved the idea. A business analyst by day and youth pastor by night, he met Denney at a neighborhood park a few years ago, then worked with him at the after-school program.

Bouie grew up in the neighborhood and knew first-hand the challenges with the public schools—not only academically (one of his daughters has been pushed along faster than she should be) but also socially (his first daughter was born when he was 16).

“I’ll never forget it,” he said of the first time Denney mentioned the idea of a Christian school to him. “I thought, That’s an incredible idea.”

But the leaders at his church were a little more skeptical. “This was a new form of ministry to them,” Bouie said. The nearest private school isn’t known for its focus on the gospel but for its sports programs, he said.

“They understood the concept of the school but not the notion of what Christ-centered education looks like,” he said.

What Christ-Centered Education Looks Like

At first, Denney wasn’t sure what Christian education in the Wilson neighborhood would look like either. So a couple of weeks after Kenosha burned, Denney visited Russ Gregg and Hope Academy in Minneapolis.

“That lunch was a turning point,” Denney said. The two biggest hurdles to starting a school are knowing how to do it and how to pay for it. In Gregg, he’d found a model he could follow. But unlike Gregg, he didn’t need to raise funds to cover tuition. Back in the 90s, Wisconsin became the first adopter of school choice. In their program, low-income students get funding (this year $8,399 for K–8, $9,045 for high school) to attend one of more than 900 program-approved private schools.

Denney and Heinrich started visiting other schools in contexts like theirs, including The Field School, just an hour south in Chicago.

“They match us in mission and vision closer than any other school in the area,” Heinrich said.

Classical Christian schools in impoverished neighborhoods teach children about God through the truth, goodness, and beauty of history, science, English, and math. But they also lean heavily into classic thinking from minority philosophers and theologians, explaining how those writers were shaped by and contributed to the classical tradition. They’re more intentional about studying minority and non-Western art and music. KCA divides its student body into groups—or houses—named for prominent minority figures such as Frederick Douglass, Katherine Johnson, and Luis Palau.

“We didn’t want to simply reproduce another version of the government schools,” said Greg Forster, a professor of systematic theology at TEDS, one of the first people Denney talked to about planting a school instead of a church, and now a KCA board member. “We wanted Christian formative education that affects every aspect of the classroom.”

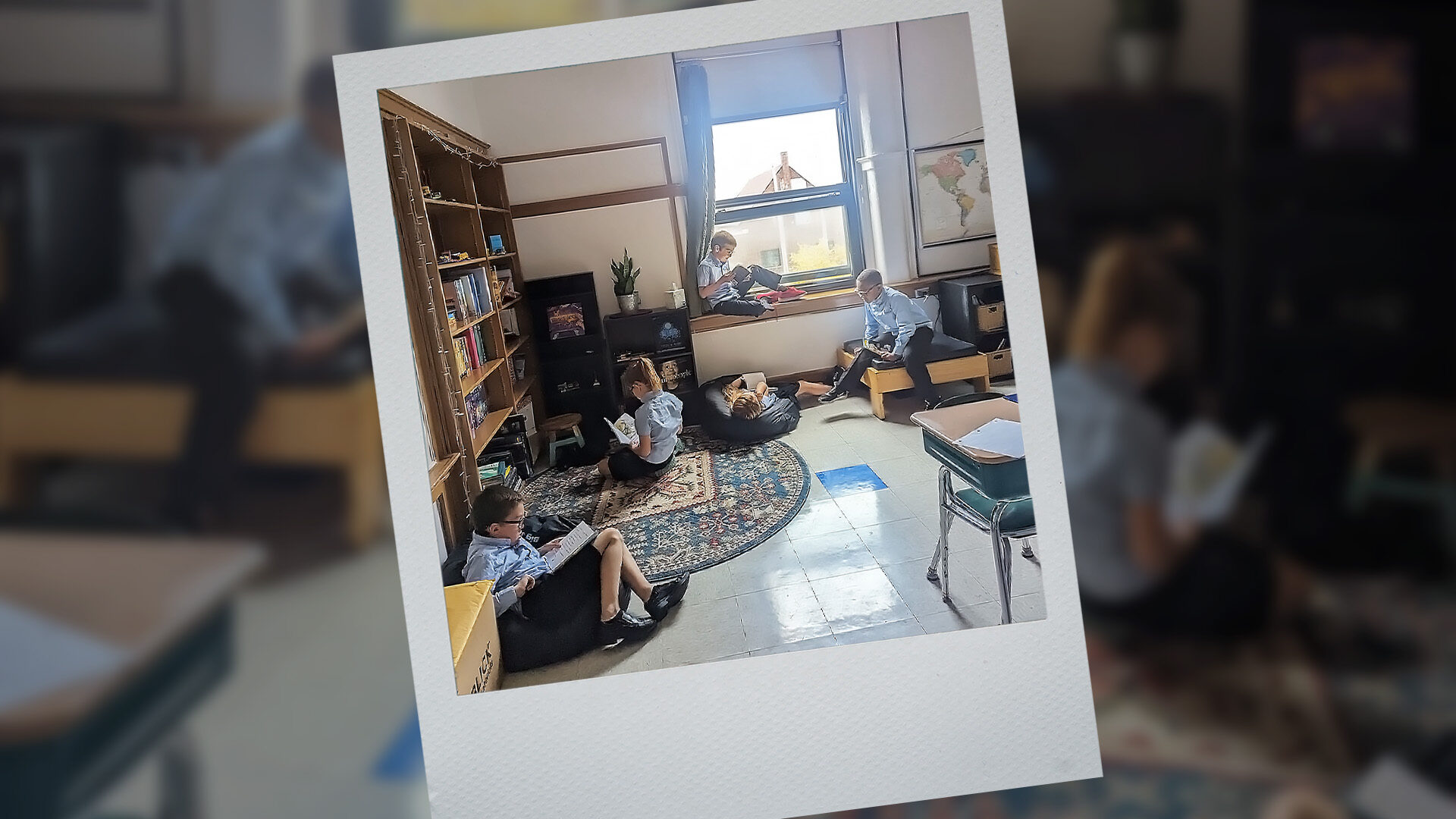

That means creating a clean, calm, beautiful space for learning; prioritizing time for playing outside; and disciplining kids with the goal of pointing them to Jesus. It also includes care for the teachers, whose load is especially heavy in this first year. After a few months, Heinrich felt like she was drowning. Denney eased back on the afternoon curriculum, adding in more reading time and structured play.

That also works better for the students, since “research shows that mastery and enjoyment in learning are better in the long-term than breadth of coverage,” Heinrich said.

For the first time in her career, she feels like she’s teaching. “We ordered curricula over the summer, and I got the pile of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths,” she said. “I just cried in the empty classroom where I was sorting them. Because I pored over those Greek myths as an elementary student when my mom fed that to me, and now I get to give it to kids whose cousins and older siblings I’d taught in a different context.”

From Theory to Practice

To be fair, her third graders weren’t clamoring for Homer on their first day.

“The first week, we did have a student try to resolve conflict with violent threats,” Heinrich said. While this child settled in, several others were unable to stay when they couldn’t follow expectations after months of support, she said.

Creating a new school culture has been challenging. Along with phonics and addition, teachers explained how they wanted kids to behave. “We believe God designed the world in a certain way, so obedience and respect and responsibility aren’t just expected so I can manage a classroom,” Heinrich said. “Those are habits we want children to form for their own good and God’s glory.”

Uniforms help to smooth the differences between income levels. About a third of the students come from stable, middle-class homes, Denney said. Another third are stable but have more financial challenges. And the final third come from financially and relationally unstable homes.

“At school, you feel like you have to fit in,” Griffin said. “I wasn’t one of the fortunate ones who always stayed dressed clean with new shoes and clothes. I like the uniform here.”

He can see Eli gaining not only reading skills but friendships and confidence.

Heinrich sees that in her classroom too. The child who was afraid enough to threaten violence is now relaxed and asking spiritual questions. Students are encouraging and challenging each other. When Heinrich reads Greek myths to them, she hears questions such as “Is Zeus like the one true God?” or “Is a hero really a hero if they don’t always do the right thing and hurt the people following them?” When she reads Narnia, they laugh together and wrestle through what it means to live with hope and faith even in the darkness.

Bouie can see the change in his son’s reading and handwriting. “I feel relief as a parent,” he said. “There’s no activity he’s behind on anymore.”

In the fall, Heinrich read aloud The Jesus Storybook Bible.

“One of the sweetest things has been to watch our kids enter into God’s story,” she said. Some of her students are biblically literate; others aren’t. “This year we worked hard to give them the same language to talk about the Bible, the same stories, the same big-picture view of who God is and what he’s doing.”

Each time she read, the kids would ask if this day’s hero was the “snake-squisher” that was promised to Eve. She kept telling them no. “They didn’t know it was Jesus until we got there,” she said. Even some of the kids from Christian homes had never thought about the Bible in this way.

When they finally reached the story of the resurrection, the kids were ecstatic. “They watched Jesus crush death and were like, ‘He’s the one!’” Henrich said. “Right after I closed the book, they asked me, ‘If Jesus crushed death, why is there still death and sin in the world?’ And we wrestled with it. These kinds of questions, wrestling with the reality of living in the already/not-yet kingdom, are an everyday occurrence. It’s great.”

“My son reads the Bible on his own now,” Griffin said. Eli is also reminding his parents to make sure they read theirs.

Shayna is thrilled. “Even my mom can see a difference in him.”

From School to Church

While the teachers and staff at Kenosha Christian Academy are believers, the parents don’t need to be.

That’s exactly how the administration wants it. Bouie, who is also on the board, compares the school’s approach to the tactics of online companies.

“Most people think Google is a search engine, but it’s really an advertising company,” he said. “They draw attention through a service that they parlay into something else.”

That’s what Bouie hopes the school is doing—giving a rich, robust education and at the same time directing children and their parents to God and to the local church. At 35, he’s one of the only men between the ages of 20 and 60 in his congregation.

“The hardest thing to do is pull in 16-to-20-year-old kids and give them an entirely different perspective,” he said. “Most of them, as they get to that age, they hear the call of the world the strongest. Most of the time, they don’t make it back to the church. In my community, that has dire consequences. You may not live. You may end up in jail.”

“The spiritual component is the most important,” Denney agreed. And since he’s interested in the whole family, he’s outside at dismissal every day, touching base with parents. He’s running Dads and Donuts, which gives him time with the fathers in the school. Every Tuesday night, his wife Catherine hosts a pizza night for a different class. Families are encouraged to come by and, slowly, relationships are starting to form. Parent-teacher conferences are mandatory, as are multiple Saturday orientations.

“Last week a student told a teacher to shut up under his breath,” Denney said. “The Saturday before, I was with his dad at Dads and Donuts. So I called him and told him what happened, and he had the opportunity to talk about it with his son. The boy came back remorseful and distraught. He said he hopes God forgives him and the teacher forgives him.” (She did.)

Denney loves that growing spiritual sensitivity among students. He loves conversations with dads who want to break long cycles of generational brokenness. He loves anticipating how this education will change the trajectory of generations in the future.

“We wanted to make a difference in a way that has a mercy ministry edge but also a significant discipleship and evangelism edge,” he said. “This school is able to do all of those things.”

“It’s magnificent,” Heinrich said. “It’s incredibly hard work. I work a lot of hours. I am tired. But it is magnificent. This is where I want to spend the rest of my life.”