One of the defining moments of my generation (millennials) was the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Sparked by generational cynicism about institutions and concern about inequality and justice, the movement gave expression to a growing sense that something needed to burn. The wealthy. The privileged 1 percent. The whole financial system. We weren’t clear on what needed to replace the current system, only that it was corrupt and needed to be destroyed.

This is emblematic of our general posture toward institutions. Scorched earth is our policy because the atomized individual—freed from the constrictions of institutional life—is our goal. Institutional bonfires aren’t a bug. They’re the feature.

Twelve years ago in Occupy Wall Street, anti-institutionalism took the form of raging against wealth, fame, privilege, and power. But in a surprising twist, today’s newest anti-institutional hero has all of those things.

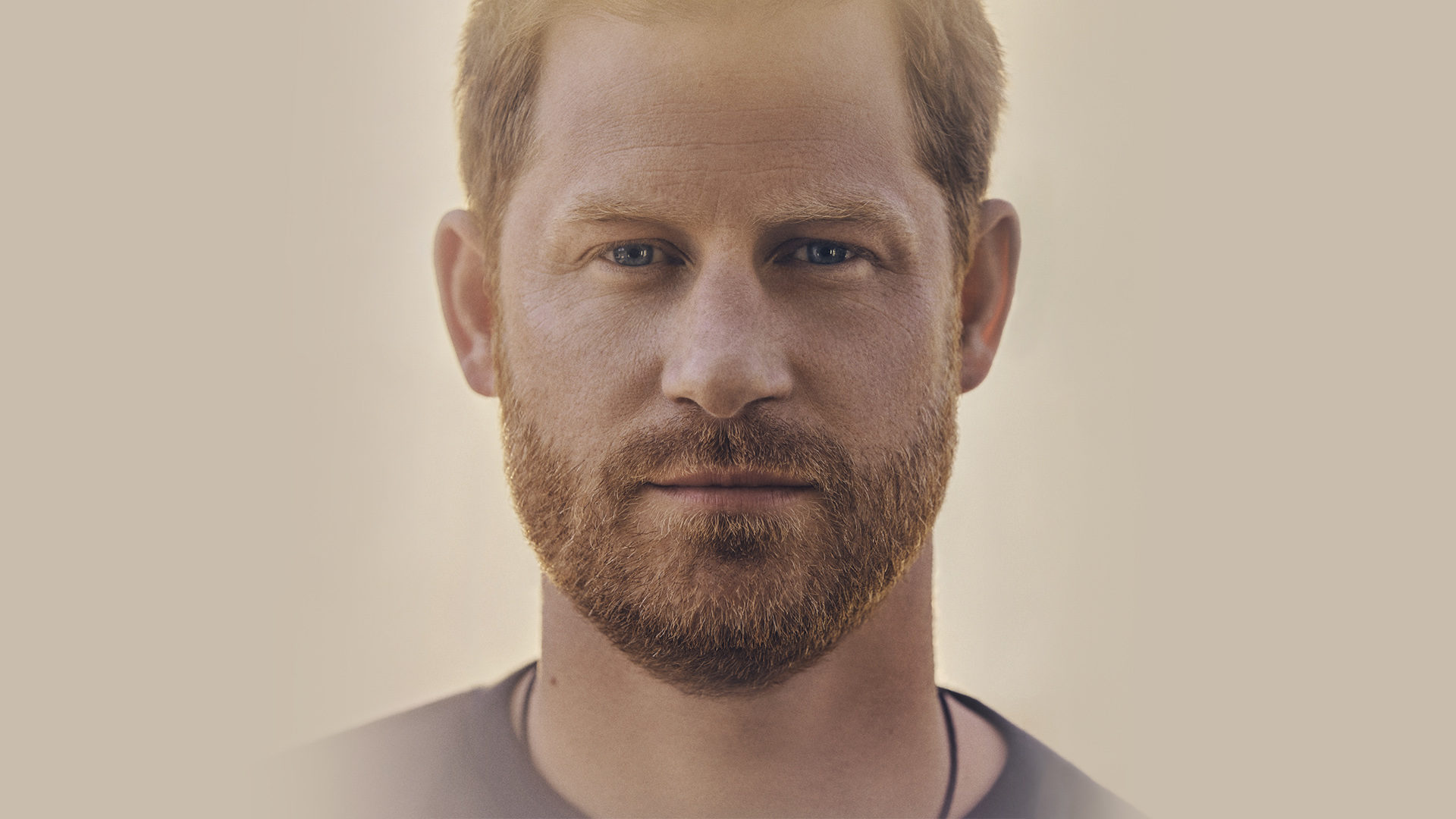

Who is the person now carrying the torch? A white man, born into tremendous wealth as a member of one of the world’s most powerful families: Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex.

Strange Hero

Harry’s autobiography, Spare, is on target to break every record for nonfiction book sales. It sold more than 1.43 million copies on its first day, unseating the previous record holder, President Barack Obama’s 2020 memoir, A Promised Land, which sold 887,000 copies on release day.

Scorched earth is our policy because the atomized individual—freed from the constrictions of institutional life—is our goal.

The difference between the books is extraordinary. Obama’s memoir has a hopeful tone and seeks to offer a positive vision for the future. Harry’s autobiography, however, is the Occupy Wall Street of the royal family. I feel profound sympathy for him: he lost his mother at an early age, lived in the shadow of his brother, and was mocked by his family as “the spare,” hounded by paparazzi, horribly misrepresented by tabloids, and endangered by the press during combat in Afghanistan.

While I find his recent decisions to thrust his family into the public eye—Oprah Winfrey interviews, a Netflix docuseries, an autobiography, and a Spotify podcast deal—somewhat confusing given his self-described hatred of fame, I suppose it may be an effort to set the record straight. I wonder at what point the record is sufficiently straightened so he can justify slipping away from public life (as much as possible) and the news media he so vociferously despises. But that’s a question for the future.

Presently, it’s more important to ask how someone who embodies so much of what my generation sought to tear down has become a hero to so many.

Queen Elizabeth’s World

The answer comes by comparing Prince Harry to his late grandmother, Queen Elizabeth II. During her coronation speech in 1953, she said to the nation, “I have in sincerity pledged myself to your service, as so many of you are pledged to mine. Throughout all my life and with all my heart I shall strive to be worthy of your trust.”

She goes on to describe her “duty” to steward her role as queen by drawing upon “the splendid traditions and the annals of more than a thousand years,” including her faith, British “social and political thought,” and “free speech and respect for the rights of minorities, and the inspiration of a broad tolerance in thought and expression.”

She speaks as a woman committed to squelching her own personality and self-expression so she can dutifully take on an externally defined role: the queen. She ended her speech by calling her subjects to cherish and practice those ancient traditions so they, too, might live out their role in society.

For Elizabeth, tradition is a launching ground, not a statue to be toppled. Society is a web of interlocking roles and responsibilities, not an atomized collection of self-expressive individuals. Social order is a trellis upon which healthy fruit grows, not a cage domesticating our inner wild.

Elizabeth embodied the ideals my generation loves to torch. So perhaps it’s no surprise a royal from my generation did exactly that.

Prince Harry’s Grievances

In a strange way, the tabloids sometimes turned out to be correct—not in the details but in the overall shape of things—about Harry’s “naughty” life. As Harry’s autobiography details, he abused alcohol, dabbled with drugs, physically bullied his bodyguards, wore a Nazi costume, used racial slurs with a Pakistani friend, was sexually promiscuous, and more. But he’s not to be blamed for this bad behavior, he argues; the institution is.

Harry is a victim, caged by a royal family that corrupted him, prevented him from processing the trauma of his mother’s death, and thereby forced him to do what his pure inner self would not otherwise do. He writes about externally imposed identities as an unending death loop, concluding, “Each new identity assumes the throne of Self, but takes us further from our original self, perhaps our core self—the child.” He compares the taking of social roles and responsibilities to shaving gold off an ingot until nothing real is left. Strip the institutions away or they’ll strip you.

Elizabeth embodied the ideals my generation loves to torch. So perhaps it’s no surprise a royal from my generation did exactly that.

The autobiography isn’t just a tell-all. It’s a burn-all. Excluding his mother and wife, no one and nothing is left unscorched: his brother and sister-in-law, his father and stepmother, Queen Elizabeth, the court, his friends, the military, the press, and more. The royal institution, like all institutions he encounters, is “toxic.” He has no sense of a role within the royal family—he’s just “the spare.” He doesn’t speak about duty positively, even as he writes about his military career: “There was a script here and I had the audacity not to be following it.”

Throughout the book, he describes encounters with animals he envies because they aren’t tamed and domesticated like him. They are wild. The book ends with the freeing of a hummingbird, and he is clearly the bird. He has freed himself by burning his cage.

I know people reading this will, correctly, point out there are deep problems with the British royal family. They’re right. There are. But I’m not writing about that. I’m simply asking the question: How did Harry become a hero? The answer is simple: he embodies the spirit of our age. In Spare, he doesn’t offer a positive vision for the future, only the indiscriminate fire of antivisions.

Prince Harry’s appeal isn’t just his celebrity and tragic story. It’s the way his story functions as an allegory for our stories: we are all spares in a larger social drama that dwarfs us and imposes rules, commitments, entanglements, and expectations upon us. Society seeks to “tame” us, shaving away the pure, childlike goodness at the core of every person by piling on roles and responsibilities. So, like Harry, we must light the match, watch it burn, and emerge unscathed as the wild, self-expressive individuals we truly are.

What Will We Build?

I fear my generation will be remembered as the generation of chaos and destruction. Even among Christians, tearing down institutions like the church has become a cottage industry of books, magazines, substacks, and podcasts. The bigger the demolition, the more clicks it garners—whether broadsides against thirdwayism or obsession with church scandal.

I fear my generation will be remembered as the generation of chaos and destruction.

The problem isn’t destruction as such. Some things are worthy of destruction. The problem is we don’t share Elizabeth’s readiness to die to herself and serve her duty unto the reconstruction of a better reality.

My prayer is that Christian millennials will come to see chaos is no better than totalitarian order. While others in our generation leave ash in their wake, we must prove the power of the resurrection by building local institutions that are good, true, and beautiful. We must understand that, yes, Babylon burned the temple as an unwitting act of God’s justice, but also that Jesus reconstructed the temple using living stones.

He calls us to do likewise.

There’s beauty in playing a role without having to be the star. There’s goodness in submitting to duty and to a vision greater than yourself—so long as it’s the vision of the kingdom on earth as in heaven.

Yes, let’s tear down what needs tearing down. But never forget that rubble makes for a poor legacy. Let’s follow Jesus’s example rather than Prince Harry’s. Let’s be the rebuilders in a generation of demolishers.