“She’s fun to talk to—always so relatable.”

“I really like her Insta account. It’s so funny and relatable.”

“She’s my favorite teacher—her stories are so relatable!”

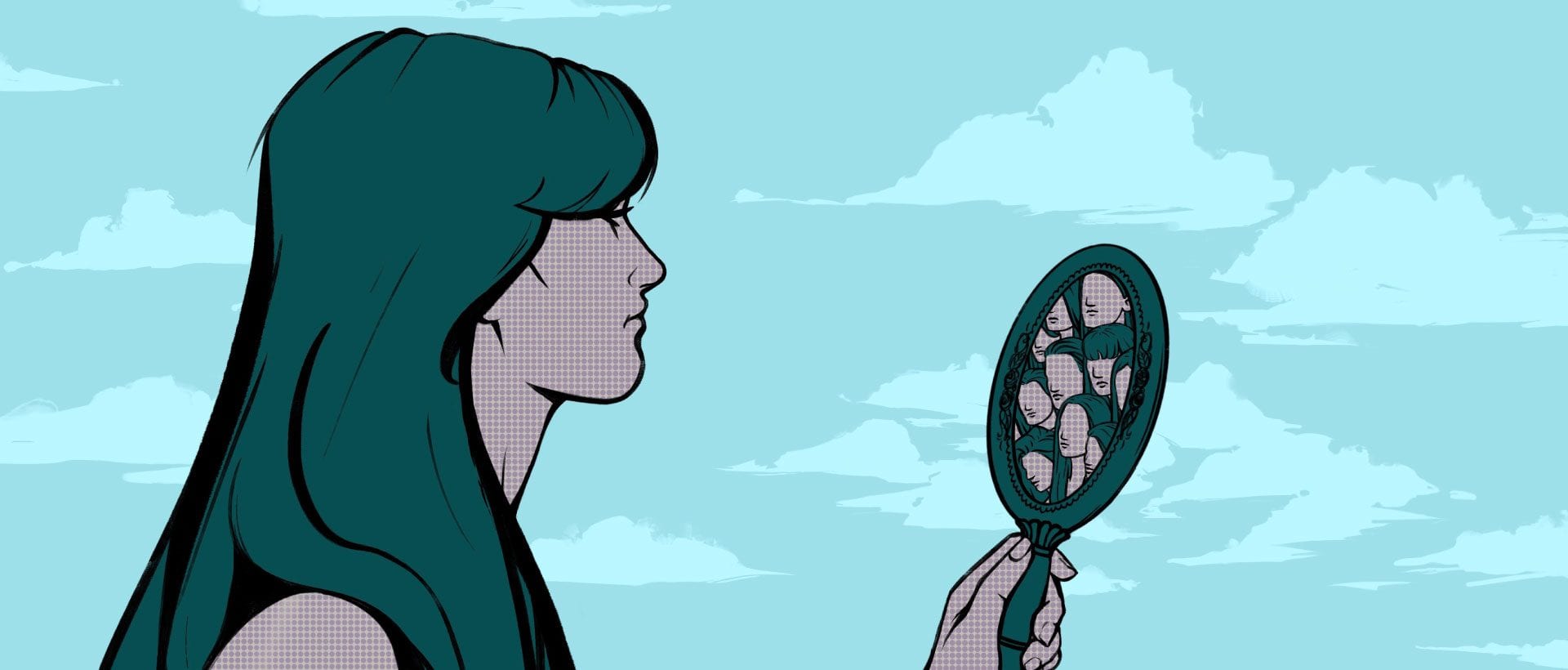

If you want to give high praise to another woman, call her “relatable.” The idea behind being relatable is exactly what you’d expect: establishing a point of connection with the person you’re talking to. It means identifying with them in some human struggle or circumstance. It means not being up on a pedestal while everyone else is down below. It means being normal (or abnormal) and not pretending otherwise.

In a digital world where filters reign and manicured feeds rule, relatability is often an antidote. It’s a way of pulling back the curtain on all those perfect images and saying the obvious: laundry exists, we have bad days, work is work, we’re often the punchline to a joke we weren’t intending to tell, and we’re all in it together.

At its best, relatability is a transparent humility that aims to serve others by providing a starting point for relationship. At its worst, it’s a longing for others to relate to our sin in a way that minimizes it. It’s a species of manipulation.

Dangerous Side of Relatability

“Oh, you yell at your kids, too? What a relief. Let’s have a laugh. So relatable.”

“Oh, you’re pouring a glass of wine and telling everyone they’re on their own for supper? Me too. I’m so sick of this everyone-needs-to-eat routine. Hahahaha. So relatable.”

“Oh, you’re binge-watching Netflix for the fourth night in a row because you just. can’t. even? Me too. So relatable.”

At its best, relatability is a transparent humility that aims to serve others by providing a starting point for relationship. At its worst, it’s a longing for others to relate to our sin in a way that minimizes it. It’s a species of manipulation.

But this way of relating doesn’t pull back the curtain quite far enough for any of us to actually experience each other’s sin or to have to walk with each other in repentance and reconciliation.

The sharing of “bad moments” is also curated and carefully chosen. It often maximizes humor and minimizes consequences. The point of sharing self-deprecating stories is to get people to like us more, not less.

That’s the power of being relatable—we love to relate to people (from a distance) who mess up like we do and who sin in the same ways we do. But we hate to be in actual relationship with people when they sin against us or we against them.

It’s not nearly as funny in real life.

Relating to Each Other in Christ

Christian women relate to one another in a different way—as set-apart women who hope in God. We will have common temptations and trials that we ought to confess and share—and our transparency can help others—but only if it leads us to our Savior together. Rather than sharing a hearty laugh over how altogether common and predictable our sin is, we join together in the uncommon holiness we’ve been given because of God’s Son who saved us from those sins (Gal. 1:4; Titus 2:11–14). Ultimately we relate to one another because we’re actually related in the family of God—by faith in his Son.

Our deepest loyalty isn’t to the shallow sisterhood of relatability or our common sin, but to our Father, who freed us from sin and made us blood-bought sisters in Christ. And yes, holy women also laugh, but not at deadly sin. We laugh at what’s to come, we laugh at what has come, we laugh at ourselves, and we laugh with a clean conscience.

When I reflect on the women and men who’ve had the most acute and lasting influence on my life, it isn’t their disarming humor and relatable stories that most influenced me.

Paul had an interesting way of relating to the church. He was quick to be transparent about his past, calling himself the chief of sinners (1 Tim. 1:15). But he was also unafraid to call people away from themselves to imitate him as he imitated Christ (1 Cor. 11:1). Many of us tend to think of humility as the thing that draws attention to our shortcomings. But Paul shows us something different. Humility is forsaking our sinful ways and following Jesus’s holy ways. It’s being honest about our inability to save ourselves. And it’s magnifying the real and powerful work of God in our lives so that we too could say to a younger believer, “Imitate me as I imitate Christ.”

When I reflect on the women and men who’ve had the most acute and lasting influence on my life, it isn’t their disarming humor and relatable stories that most influenced me. In many cases, I couldn’t relate to their experiences at all. I can’t relate to Betsy ten Boom’s contentment in a concentration camp, or Elisabeth Elliot’s weathering the loss of a murdered husband while ministering to the ones who murdered him, or even John Piper’s forsaking a television. I can barely relate to my own mom’s endless service of babysitting at the drop of hat or my dear friend’s unwillingness to go near anything that has even the faintest whiff of gossip. And that lack of “typicality”—the fact that I can’t immediately relate—is precisely what calls me away from the longing to be normal or relatable or typical and into greater desire for holiness and greater desire for the God who empowers such atypical living.

In their set-apartness, they beckon me to Christ, the ultimate sympathetic high priest, who relates to us in the most powerful way of all. He became one of us to show us the way out of our common, relatable sin and into his uncommon, joyful holiness. Sisters, let’s follow him.