Join Alan Noble and Mike Cosper for their workshop at the 2019 TGC National Conference where they will speak on “Disruptive Witness: Speaking Truth in a Distracted Age.” You can browse the complete list of 74 speakers and 58 talks. The conference is fast-approaching, so register soon!

When Christians interpret, critique, and discuss stories with our neighbors, we can model a contemplative approach that promotes self-reflection and honesty, inviting empathy rather than promoting the detached rationalism of the buffered self. We can lean into the cross pressures produced by these stories. We can offer interpretations that affirm and account for our longings for forms of beauty, goodness, order, and love that find their being beyond the immanent frame of our secular age.

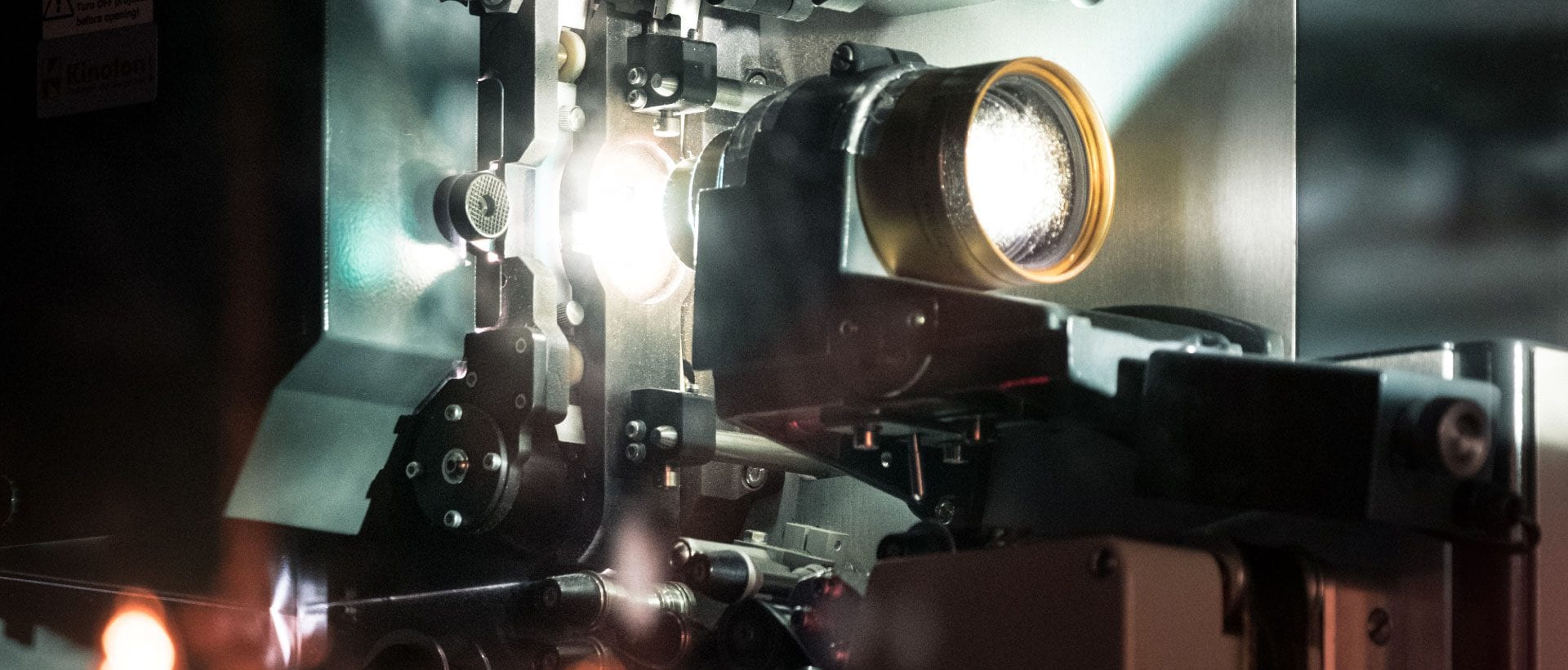

By “stories” I don’t just mean novels. I’m referring to all the cultural works that involve narratives: films, TV shows, songs, albums, plays, commercials, video games, and so on. Obviously, most stories aren’t thoughtful and compelling enough to invest time in, but there are a great many that are worthy of praise and attention. We participate in stories when we receive them charitably and dialogue with others about how to interpret them. Participation is the combined act of receiving (watching, listening, reading, seeing, etc.) and dialoguing (writing reviews, critiquing, arguing about a film’s ending, and so on). According to this definition, virtually everyone in America is participating in stories everyday—grandmothers who speculate about a cliffhanger on a soap opera, users who add annotations to lyrics on Genius.com, or friends discussing a film they just saw in a theater.

Participating in stories is a vital part of culture, and it is not a coincidence that it has so much capacity to disrupt our understanding of the world.

Seeing Beyond the Frame

Stories allow us to question our vision of fullness and consider alternatives. And because stories can convey a world, they can help us imagine new paradigms, whole new ways of understanding life, like the possibility that there is reality beyond the immanent frame.

Given the ability of stories to create this space for imaginative reflection on meaning and existence, it shouldn’t be surprising that Charles Taylor, in A Secular Age, points to literature as one of the ways modern people can envision a paradigm shift out of the immanent frame (732). Taylor argues that converting from something like a materialist view of the world to a spiritual one is not merely a change in beliefs. It involves changing our background assumptions about life. This kind of change requires new ways of speaking, new languages that resonate more fully with people who are deeply inured by the closed, immanent frame.

Many of the great founding moves of a new spiritual direction in history involve a transformation of the frame in which people thought, felt and lived before. They bring into view something beyond that frame, which at the same time change the meaning of all the elements of the frame. Things make sense in a wholly new way. . . . There was something very disruptive of existing habits of thought, action, and piety. (731)

Asking people to see beyond the frame is extremely difficult, because the frame of the immanent world is our background assumption, and what we can’t see is hard to look beyond. It takes a work of imagination to go beyond—a spiritual imagination. Stories provide the space for this imagining.

Intimations of Transcendence

In a well-crafted story we not only rationally consider the vision of the world created by the artist or artists, we also enter that world. And good storytelling invites us to empathize; we viscerally feel the world and the values and ideas that govern it.

Stories provide models for ascribing meaning to our own lives, which makes stories ideal for the kind of disruption Taylor has in mind. His focus is specifically on how Christian authors and poets can help those of us stuck in the immanent frame to imagine a world beyond, without taking us out of this world in a gnostic fashion (732).

But we can take Taylor’s claim a step further. For those of us who are not artists, our participation in other people’s stories can also “break from the immanent order to a larger, more encompassing one, which includes it while disrupting it” (732). Our interpretation and dialogue about stories can help our neighbors “feel the solicitations of the spiritual” as they appear in art (360). Our cultural participation can challenge the buffered self by showing that “part of being good is opening ourselves to certain feelings; either the horror at infanticide, or agape as a gut feeling” (555). With discernment, charity, and dialogue, Christians can participate in stories in disruptive ways that challenge the distracted, secular age.

With discernment, charity, and dialogue, Christians can participate in stories in disruptive ways that challenge the distracted, secular age.

In concrete terms, this participation might involve going to a movie theater with a friend and talking about the film afterward, book clubs, discussing the latest episode of a TV show with a coworker, hosting parties for watching a TV show that intentionally include time for dialogue, hosting movie nights, or making time to talk about an album with a group of friends. Again, virtually all of us in America do this sort of thing to some extent. Stories of one kind or another are at the heart of our culture, and we relate to one another by sharing them and interpreting them together. I’m recommending that we be more intentional about our participation in stories in specific ways, in order to make the immanent frame more visible and to interpret intimations of transcendence toward the more satisfying and fulfilling account of existence found in Christ.

Haunting Stories

Practically, this means choosing aesthetically excellent stories, whether or not they are the most popular. These stories will tend to be darker or more depressing or heavy, which sounds unpleasant. But Christians should be known for their appreciation of tragedies, because in good tragedies we must reckon with our place in the world, the problem of evil, and the struggle for meaning. (In the classical sense of the term, comedies can also make us face these difficult realities, but in the contemporary world, this is less true.) All those questions and concerns our distracted age is good at helping us ignore come to the fore in stories that deal with the tragic element of life.

I am not asking Christians to stop seeing superhero movies or listening to pop music, but we need to be mindful of how we use our time. Many of the popular stories in our culture leave us worse off. Instead of haunting us, they glorify vice, distract us from ourselves, lift our mood without lifting our spirits, and make us envious and covetous of fame, sexual conquests, and material possessions.

Christians should be known for their appreciation of tragedies, because in good tragedies we must reckon with our place in the world, the problem of evil, and the struggle for meaning.

When a story haunts us, it troubles our buffered self; it intrudes on our thought life, makes connections to other stories and experiences and ideas, and compels us to contemplation. More often than not, this haunting is a manifestation of Taylor’s cross pressures. This doesn’t mean we should watch or read content we find objectionable or that we should only watch serious movies. A story that captures the beauty of creation or the imagination can haunt us just as much as a deadly serious story.

Every time I watch Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory I am haunted by Dahl’s vision of wonder as captured so beautifully by Gene Wilder. Here is a world in which the immanent frame has a chocolate-factory-size hole in it. The final song in the movie, “Pure Imagination,” is about retreating to a world of “pure imagination” where anything is possible, a world that Wonka calls “paradise.” The lyrics (not written by Roald Dahl) are corny and heavy-handed, but with Wilder’s sincerity, we begin to feel awaken within us a genuine longing for paradise, not unlike the experience of hearing Judy Garland sing “Over the Rainbow.” When the song and the credits end, I am left with the feeling that there ought to be paradise, and I am reminded of C.S. Lewis’s famous quote: “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” We do not need to only participate in dark or troubling stories, but we do need to give priority to stories that haunt us, unsettle us, and expand us, whether through beauty and delight or tragedy.

Revealing Cross Pressures

We also need to make time and find space to interpret the stories through dialogue with others. Living in an atomistic culture, our default response to receiving a story is not to interpret it in community. We may have a personal opinion about it. We may tweet a 280-character review. We may debate parts of the story. But most of us are not inclined to take the time to slowly work through the meanings of the story in dialogue with one another. In other words, the prolonged, thoughtful, charitable dialogue about stories I’m recommending will not happen naturally. We need to intentionally pursue it.

The goal of this kind of dialogue is to reveal the points of cross pressure in the story, to consider the visions of fullness it portrays, and to relate it to the world as we know it.

Editors’ note: This is an adapted excerpt from Disruptive Witness: Speaking Truth in a Distracted Age.