“It’s a shame he was an adulterous and unfaithful husband, but he sure was a great theologian and a gift to the church.”

Is this sentence intelligible? Might it be regarded as capturing the complex reality of indwelling and ongoing sin for theologians, or is it simply oxymoronic? Part of how we answer the question depends on additional information. Was this adultery a single occasion or a persistent reality? Does this theologian out himself in broken and contrite confession and repentance, or does he justify his actions and remain habitually unrepentant?

I’d imagine most of us would instinctively conclude that if the “theologian” in our thought experiment engaged in high-handed and unrepentant habitual adultery, the descriptor “adulterous and unfaithful husband but splendid theologian” is nothing more than an oxymoron.

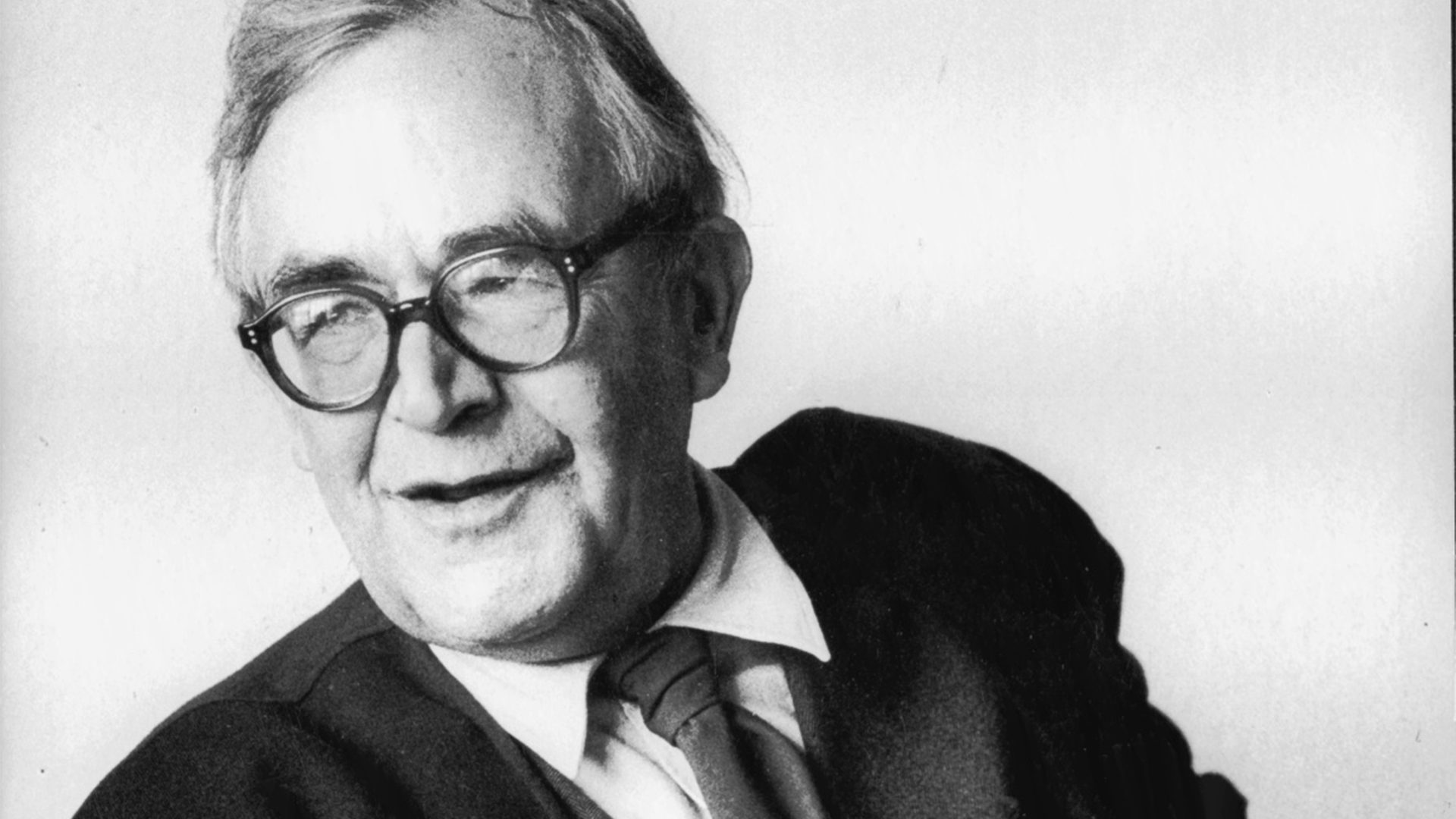

And we haven’t been thinking about a hypothetical figure; we’ve been thinking about Karl Barth, who is regarded by many as one of the most important theologians of the 20th century.

Karl Barth and the Handicap of Habitual Sin

Most theologians and historians have engaged with Barth’s work without having to address the question of his relationship with his assistant, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, for the simple reason that no one could confirm whether their relationship was anything more than professional. With the recent discovery of Barth’s private correspondence with Kirschbaum, the ongoing romantic affair has become incontrovertible.

The descriptor ‘adulterous and unfaithful husband but splendid theologian’ is nothing more than an oxymoron.

Barth not only pursued a long-term romantic courtship with Kirschbaum but also invited her to live with him and his family. This put incredible strain on his relationship with his wife, Nelly, who wasn’t oblivious. In fact, her depression was so severe that at one point she put an ultimatum to Barth: either Kirschbaum moves out of the house, or Nelly would do the unthinkable and divorce him. Barth, ever committed to rational and well-thought-out actions, responded by calling a meeting between himself, his wife, and his mistress to talk the matter over. The result was that Nelly received a “no” to her ultimatum, and she was effectively forced to remain living with her adulterous husband and his mistress.

I don’t bring up Barth merely to hash out the salacious details of his adulterous sin or his cruelty toward his wife but rather to consider how all this factors into our assessment of Barth as a theologian. How might this high-handed and habitual unfaithfulness have influenced his theological contemplations?

Asking this question isn’t an exercise in the fashionable tendency to “cancel” theologians from the past in the spirit of self-righteousness. Nor is it a demonstration of speculative psychologizing. Barth himself wasn’t silent in his private correspondence with Kirschbaum about how he conceptualized their affair from a theological perspective. Indeed, he readily admits his actions affected how dogmatic he allowed himself to be. “A strange consequence of our ‘experience’” writes Barth, “will be that my seminar this summer about the recent history of theology will turn out much more lenient, merciful, cautious than it would have been the case otherwise!”

Barth would even go so far as to justify his sin theologically. At one point, he says to his mistress, “It cannot just be the devil’s work, it must have some meaning and a right to live, that we, no, I will only talk about me: that I love you and do not see any chance to stop this.” According to Barth, the pious option was to remain in the tension between the revealed commands of God’s Word and the assumed ordination of God in his love for Kirschbaum. It couldn’t possibly be that God intended for him to deny his affections for a woman who wasn’t his wife—even though this is what Scripture clearly teaches.

So he concludes God has purposes to keep him in this tension: refusing to divorce his wife and refusing to deprive himself of his relationship with Kirschbaum. “Thus I stand before the eyes of God, without being able to escape from him in one or the other way.” God, according to Barth, has placed him in an impossible dilemma, where the closest thing to obedience, and the most pious option, is to stay in an adulterous relationship.

Gregory of Nazianzus and Consecration

This is bad theology. How could someone as undeniably brilliant as Barth reason so poorly? If we could consult another influential theologian from the past, Gregory of Nazianzus, he would insist Barth’s sin couldn’t do anything other than produce a handicap in his theological contemplations. Jesus meant it when he said that it’s the “pure in heart” who will see God (Matt. 5:8). With Barth, or any other theologian, the way a person lives affects the way he thinks.

That’s why Gregory writes at length on the notion of theological consecration. “Discussion of theology is not for everyone,” he says, “but only for those who have been tested and have found a sound footing in study, and, more importantly, have undergone, or at the very least are undergoing, purification of body and soul. For one who is not pure to lay hold of pure things is dangerous, just as it is for weak eyes to look at the sun’s brightness.” In other words, Gregory stresses caution. It’s not possible to do theology well in the abstract, without attending to our personal piety.

With Barth, or any other theologian, the way a person lives affects the way he thinks.

Gregory stresses the significance of purity of heart when approaching God because of God’s holiness. To approach the Holy One in any capacity (including intellectually) is to approach the One who is a consuming fire (Heb. 12:29)—we can’t avoid the heat of his holiness. God’s own nature doesn’t give us the option of contemplating him rightly in a compartmentalized sense, where we consider him with accuracy intellectually but with cold hearts and impure hands that are distant from him. To the degree we contemplate God rightly, we’re participating in his divine mind—we’re thinking God’s thoughts after him—which is so holy that it cannot do anything but make holy what’s in its presence.

This way of thinking exposes our modern assumptions. We may imagine the ideas that come out of a person are completely disconnected from his body and soul. We may imagine a theologian can be assessed without any consideration of his life and conduct. But we’re forgetting what theologians are for.

Christ gives the gift of “teachers” to his church (Eph. 4:11–14). The theologian who doesn’t make it his central ambition to build up the church ends up in a Samson-like position: having been given by the Lord to Israel for her deliverance and protection and benefit, he selfishly pursues his own gratification, benefiting those he was assigned to only when it’s convenient for him and when their needs overlap with his selfish pursuits (see Judg. 13–16). But his (theological) strength does not exist for himself, and he shouldn’t behave as if it does.

We can even go so far as to say the theologian’s godliness, which enables him to see God rightly, is cultivated. He needs the accountability of fellow brothers and sisters in Christ, and they need the teaching he provides, so that “the one who is taught the word” may “share all good things with the one who teaches” (Gal. 6:6).

Refuse to Settle for Ungodliness

I can think of at least three immediate implications for all of us in light of this meditation on piety and theology.

1. Don’t settle for impious theologians.

Though we dare not require perfection from our theologians, we must insist upon ever-increasing purity of heart. Settling for anything less should be unthinkable. If theologians are teachers whom Christ has given to the church, we should expect more from them than a “Dr.” title and a sharp mind.

We need theologians who are strengthening the church from the inside, attending to their own lives with godly earnestness and a willingness to “one another” fellow church members. Purity of heart doesn’t come apart from a clear concern for personal and communal holiness. If purity of heart is a prerequisite for seeing God (Matt. 5:8), the church simply doesn’t need the theologian who won’t pursue holiness in the context of local church membership. He can’t help the church see God because he’s unable himself to see God.

2. Don’t settle for impious pastors.

Pastors are the preeminent shepherd-teachers, tasked to care for the flock of God. If these principles and standards apply to anyone, they surely apply to pastors, which is why the most memorable and straightforward passages emphasizing the relationship between doctrine and piety are in the pastoral epistles (e.g., 1 Tim. 3:1–13; 4:16; Titus 1:5–9; 2:1–15).

We’re all exhausted by the seemingly endless train of pastors who crash and burn and disqualify themselves publicly. If this trend shows us anything, it’s that we’ve failed to reckon with what the Scriptures teach: character, not charisma, is the most important prerequisite for pastors. So let’s not settle for brilliant, charismatic, energetic, creative, winsome, impious pastors. Let’s expect purity of heart from those who are to shepherd our souls.

3. Don’t settle for impiety in your own life.

R. C. Sproul’s remarkable book Everyone’s a Theologian teaches a valuable lesson with its title. Too often we think contemplation of God is the work of professional theologians and pastors and that their job is simply to condense down for us the “so what.” But Christ gives teachers to the church in order to help the church see what they see.

The sooner we realize knowing God isn’t a means to an end but rather the greatest end and final purpose of all our lives, the better. The culmination of all our contemplations of God here in this life is the very thing that makes heaven heaven: the blessed sight of God (1 John 3:2; Rev. 22:3–4). All roads of desire for God lead there. We want to see God. And if we want to see and know God rightly, then purity of heart is nonnegotiable—for Karl Barth and us as well.