This fall, LifeWay Christian Resources started looking for a new president.

He or she will have to be a spiritual leader and a change agent, but also have financial and business acumen, according to the job description. The new president should be a strategic, humble, and inspiring leadership developer. He or she should have integrity and credibility, be inclusive, and have a good work ethic. The candidate should be a good strategizer and a good communicator, be able to hold himself or herself accountable, and possess a high emotional intelligence.

“The presidency of LifeWay is a role like none other,” said LifeWay director of strategic initiatives Jonathan Howe. “The list of responsibilities is baffling—you need Southern Baptist credentials plus wider evangelical respect plus business acumen plus theological soundness. Finding that in one person is next to impossible.”

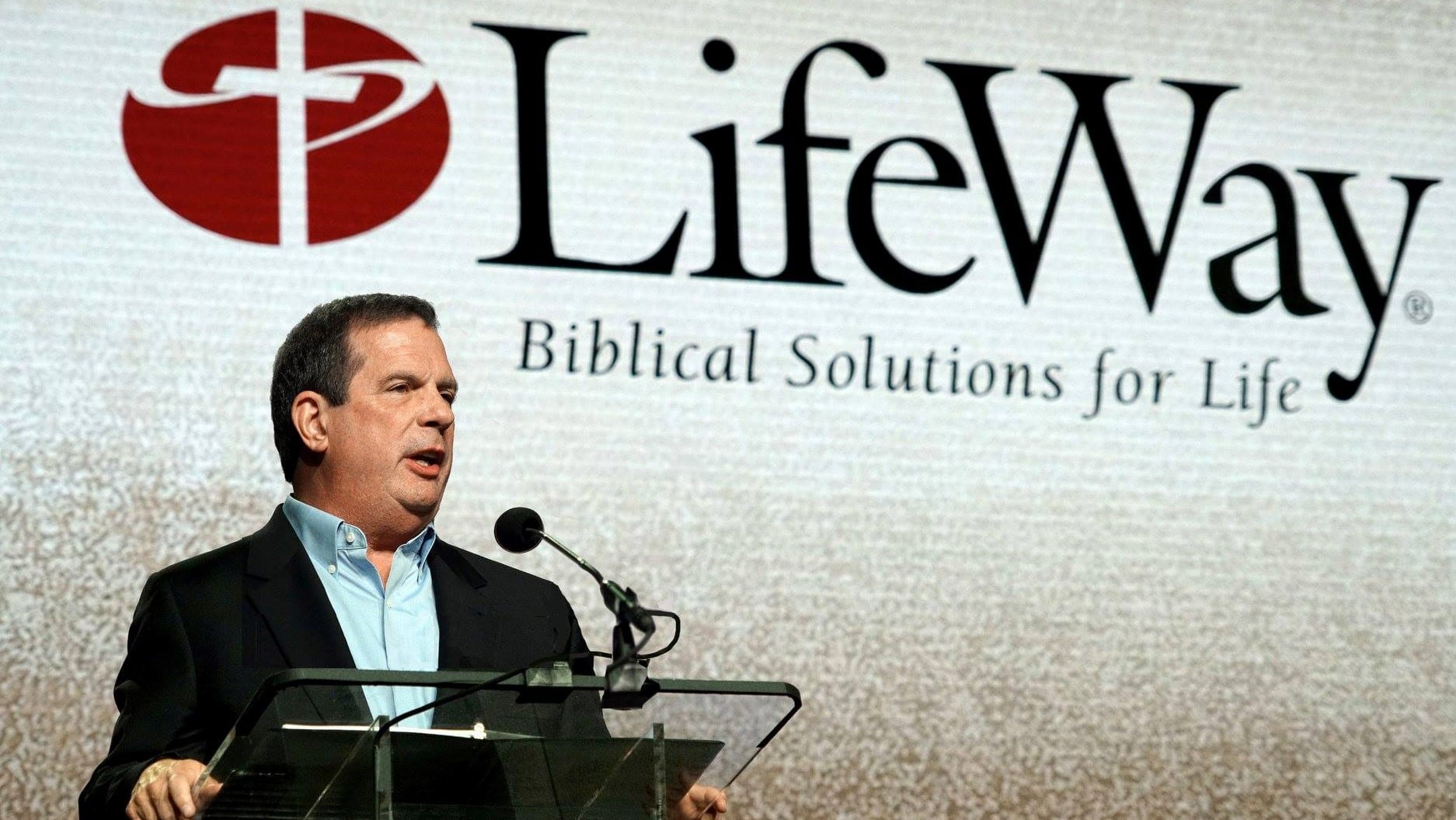

Thom Rainer, the 63-year-old retiring LifeWay president, is “a once-in-a-generation leader,” Howe said.

It’s hard to argue. With a background in finance, an MDiv and PhD from The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (SBTS), and a dozen years of serving as the founding dean for the Billy Graham School of Missions and Evangelism, it’s easy to see why LifeWay hired him in the first place.

It’s a bit harder to see why he came on board in 2005.

“LifeWay was not in the plans,” he said. “I didn’t like their resources.”

That wasn’t all he didn’t like. After publishing six books with them, concerned by the “poor services and products,” he dropped B&H (LifeWay’s book imprint) and signed his next four-book deal with rival Zondervan. He also stopped speaking at LifeWay events.

“I thought B&H was poorly managed,” he said. “Back then, they were publishing a lot of weaker books. The quality was low, the editing was low, and the relationships were weak.”

When the letter came asking him to be a candidate for president, he called it a joke and tossed it aside.

But his wife, Nellie Jo, picked it up. And just before the deadline, she dared him to apply.

“I kept this letter because I thought it would be a good souvenir,” she told him in humor. “I guess you’re not going to apply. I know you, Thomas. You’re afraid you’ll be turned down.”

Rainer looked at her.

“Gimme that letter,” he said.

From Banking to Ministry

Rainer’s dad was a banker. So was his grandpa, and his great-grandpa, and his great-great-grandpa.

“I went to the University of Alabama and got a finance degree,” Rainer said. “I got a job with a large bank in Atlanta, and later accepted another job with another large bank. I was going up the career ladder more rapidly than anticipated for a 20-something.”

But the whole time, he kept feeling the tug to ministry.

“I came home one day and told my wife that ‘I can’t resist this call any more. We need to go into ministry,’” Rainer said. “She said, ‘I’ve been waiting on you.’ She knew before I did.”

Rainer put in his two weeks’ notice, packed up his wife and two small boys, and started driving to SBTS in Louisville. It was 1983.

Partway there, “I happened to remember that I had not applied,” he said. “We stopped in Birmingham, and I filled out an application and put it in the mail. Then we kept on driving.”

The Rainer family got to SBTS before his application was processed, but Rainer was able to beg his way into some student housing. He took a job as a janitor at Lee’s Famous Recipe Chicken before a bank offered him 30 hours a week as a corporate loan consultant.

On top of everything else, he went to class. But seminary was nothing like he expected.

Southern Turn

“I was naïve, thinking we’d all be holding hands and praying the whole time,” said Rainer of SBTS. “It was difficult because Southern was largely liberal at that time. Some of the professors didn’t believe in the bodily resurrection. Some of them used profane language. It was awful, but a refining time as well.”

He didn’t stop with the overachieving, stacking a PhD on top of an MDiv and pastoring two churches while in school. He was at his second post-seminary church when SBTS president Al Mohler asked him to be a founding dean at the Billy Graham School of Missions, Evangelism and Ministry.

“I was at Southern for 13 years,” Rainer said. “I saw the biblical revolution take place. . . . I got to see the beginning and end. It was an incredible story.”

Rainer was at SBTS when the LifeWay letter came, and he applied to prove he could get the job. But as the field narrowed—from 15 top candidates to 10 to 5 to 3—he started to really want it.

“I don’t know if it was a sanctified desire, or if I was just competitive, or if God was using my competitiveness,” Rainer said. “But my desire became greater.”

He was elected in 2005 and took office in 2006. That’s when the competitive fever wore off.

“Every day I’d think, Oh, no, I didn’t want to do this,” Rainer remembers. “What am I doing here?”

Baptist Sunday School Board

The first time the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) tried to publish its own Sunday school curriculum, it was 1863 and the institution was less than 20 years old. The Southern Baptist Sunday School and Publication Board couldn’t gain traction in the aftermath of the Civil War and lasted only 10 years.

Most Southern Baptists felt they could just use the materials printed by the northern Baptists, but pastor J. M. Frost, armed with his wife’s $5,000 inheritance and lots of determination, fought to get the Baptist Sunday School Board approved by the convention in 1891.

The deal: He could publish materials, but no SBC church was obligated to use them, and he’d have to earn his own money.

Over the past 127 years, the Baptist Sunday School Board added to books and videos and Bibles and hymnals to its Sunday school curriculum. It opened physical bookstore locations and convention centers; it built the tallest office complex in Nashville. In 1998, it changed its name to LifeWay. Today, it employs more than 5,000 people.

But it’s hard to keep energy up and sales rising and morale thriving for more than a century. By the time Rainer came on, LifeWay’s flagship resource—the curriculum for Sunday schools and Bible studies—was in a 30-year decline.

One reason for that was waning denominational loyalty across the country. But another was simply that “quality was low,” Rainer said. “Our resources have to be of the highest quality, and not from a pure marketing point of view. When someone picks up our curriculum or books, or goes to one of our events, one of the first things we want them to say is, ‘Wow. God is really honored through this.’

“Frankly, that was not the case in many areas of LifeWay.”

Rainer knew he wanted better products. “But you can’t just mandate, ‘Give us better stuff.’”

To get there, he knew he needed a different culture.

Good People

“I am not the brightest bulb in the chandelier,” Rainer said, “but I can tell you one thing I can do. I can bring good people around me.” (He may also be one of the brightest bulbs—former LifeWay vice president Eric Geiger says “you realize more and more how smart he is the more you’re around him. He’s a freak-of-nature genius.”)

Rainer hired Brad Waggoner—“one of the most unsung heroes in evangelicalism”—to start up a research branch, then hand it off to the high-profile researcher Ed Stetzer. “We wanted not only the denomination but the greater evangelical world to know that LifeWay knows our subject matter,” Rainer said.

Rainer next asked Waggoner to run the B&H Publishing Group imprint, created when LifeWay’s Broadman Press publishing arm bought the A. J. Holman Bible Company. A few years later, Waggoner passed it off to Selma Wilson and became executive vice president of LifeWay itself.

Every hire Rainer made, he was looking for three things—character, competency, and chemistry.

And that’s when everybody knew for sure the culture was changing. Because only men sat at the executive table at LifeWay, and Wilson is a woman.

“He values women,” Wilson said of Rainer. “He values diversity. . . . I’ll have people say, ‘Tell me about the conflict you had,’ but I never had conflict [on the executive team] as a woman.”

Every hire Rainer made, he was looking for three things—character, competency, and chemistry.

“I don’t think I ever made a bad character hire,” he said. “But sometimes I’d skip from character to chemistry without looking at competency. LifeWay is fun but challenging work, and it can be grueling. Since 1891, we’ve never received outside funds—what we earn is how we make our way.

“I haven’t always gotten it right,” Rainer said. “Some of the most difficult conversations are where people I have a good relationship with didn’t make it because they weren’t the right fit at the right time.”

Another occasional mistake was giving too much freedom.

“You want to bring in people who, instead of goading them to go faster with a spur, you have to pull the reins and say, ‘Whoa,’” he said. “You want to err on the side of letting them make mistakes rather than controlling them to conform in your image.”

Some people’s reins had to be pulled more than others.

“When I came to LifeWay, they eventually asked me and my team to come up with some new ministry initiatives,” Stetzer said. “The first one we came up with lost $100,000.”

“Well, you learned what doesn’t work,” Rainer told him. “Let’s try something else.”

Stetzer’s next project broke even. The one after that was a new curriculum that would develop into The Gospel Project.

“There was space to fail,” he said. But not endless space.

“Certainly, if I failed five times in a row I wouldn’t be there, because LifeWay is a business,” Stetzer said. “I’ve worked at large Christian organizations where it’s really hard to lose your job. People just stay. But businesses have to make hard choices, and Thom would make those hard choices.”

Culture Change

Sure enough, with the right people, LifeWay’s culture began to change. But Rainer also made direct changes to spur that shift along.

The best and clearest example was the dress code.

As late as 2011, LifeWay had express dress requirements for its employees. Women couldn’t wear capris. Executives had to wear a suit and tie, and while the suit coat could be removed inside the person’s own office, it had to be donned again if the executive left the room. Fridays everyone could dress down—to business casual.

“It was extreme,” Rainer said. “It had become command-and-control dress code.”

And that’s not Rainer’s style. So one day at chapel, he made a casual, off-handed announcement.

“By the way, I’m really tired of this dress code,” he said. “Y’all are grown men and women. You know how to dress. The dress code is gone.”

He did not expect their reaction. Employees “went wild,” clapping and cheering, Wilson said.

Someone yelled out, “Does this mean jeans?”

“Sure, if that’s appropriate,” Rainer replied.

They gave him a standing ovation.

It seems like a simple change, one almost too small to note. But “it was part of the culture shift,” Rainer said. “It was a signal to the employees that we trusted them.”

Laughter

After that, Waggoner took on the rest of the policy manual.

“LifeWay had a policy that said, basically, ‘No hanging out in the hallway chatting,’ which usually ended up in laughter,” Rainer said. “Obviously, Waggoner did away with that when the policy manual was redone.”

Rainer isn’t a clown. He’s not gregarious or even extroverted. But he is quietly hilarious—he’s got a quick, dry wit and a well-developed ability to play. He’s the one who will start singing a Beatles song in the middle of a tense meeting, ask you to pray right after you take a huge bite of your sandwich, or tweet “I’m so excited the Stetzers are having twins” on April Fools’ Day.

Rainer “brought the gift of laughter to the culture of LifeWay,” said Wilson, who also loves to laugh.

“It made him more human,” Geiger said.

It’s hard to overestimate that shift.

“I was there before Thom, and LifeWay was pretty rigid and very hierarchical,” Wilson said. “He’s broken down a lot of those walls to be more collaborative and innovative.”

Which meant Rainer was right—changing the people changed the culture. Now for better products.

The Gospel Project

LifeWay’s bread and butter has always been its curriculum for Sunday school and small-group Bible studies.

But for decades, sales kept slipping. The staff chalked it up to an overall drop in Sunday school attendance and number of Bible studies. But Rainer wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

His team “recognized that we weren’t really serving as many people in our churches as well as we could,” LifeWay director for Bibles and reference Trevin Wax said.

“We didn’t want to push churches to get [our curriculum] out of denominational loyalty,” Rainer said. “We wanted churches calling us to say, ‘I want that.’”

Stetzer and Wax brought together teams of people to write and edit and coordinate an ambitious new project—a three-year, chronological, gospel-centered, missional curriculum. Everyone—preschool through adults—could use it. And the print copies would be supplemented with digital resources—images and songs and videos.

Every year since it began, The Gospel Project has been bigger than the year before.

“In the initial launch, in the fall of 2012, our hope was that maybe 40,000 or so people would buy this,” Wax said. “If we could have done that, it would’ve been the biggest launch LifeWay had seen in 12 to 15 years.”

Instead, 493,000 participants wanted The Gospel Project curriculum in the first quarter.

“We had printing issues,” Wax said. “It was crazy. . . . Every year since it began, The Gospel Project has been bigger than the year before.”

This year, about 1.5 million people are using it.

The Gospel Project’s wild success spurred LifeWay to “relaunch and reinvent” their two other major curriculum lines—Explore the Bible and Bible Studies for Life. This fall, sales in all three lines were growing.

“That put LifeWay in different posture,” Rainer said. “People started looking at us and saying, ‘Something different is happening there.’”

But even moving a lot more curriculum couldn’t solve LifeWay’s biggest financial struggle.

Amazon Challenge

“Amazon and the digital world has been our greatest business challenge,” Rainer said. He knows he’s part of the problem. “I’m a classic introvert. I don’t like the in-store shopping anywhere. I do it as little as possible.”

Because LifeWay produces its own products, and because most of its sales are directly to churches, its bookstores are a little better positioned than other brick-and-mortar Christian bookstores—such as Family Christian Resources (FCR), which closed its 240 locations in 2017. Last summer, LifeWay even opened a few more stores in vacant FCR spaces.

Under Rainer, LifeWay leaned into online sales. But it still operates about 170 stores, and the challenge of maintaining a brick-and-mortar presence in a digital world will largely be left to Rainer’s successor.

To prepare for that, Rainer has worked to get LifeWay into a healthy financial position.

That meant reorganizing departments and cutting personnel. It meant selling LifeWay’s 1.1 million-square-foot headquarters to build a 277,000-square-foot space five blocks north. It meant softening policies to let employees work remotely, which both relaxed the culture and saved on office space.

And it meant selling the Glorieta Conference Center, a 2,100-acre camp near Sante Fe, New Mexico. The conference center had lost money for 24 out of 25 years by the time Rainer decided to pull the plug.

As business decisions go, it was a no-brainer. But selling the conference center was the only time Rainer thought he might have to quit LifeWay.

Second Home

In the late 1940s, the SBC was looking for a conference center in the west to balance out Ridgecrest Conference Center in North Carolina. It charged LifeWay (then the Sunday School Board) with “raising funds, erecting buildings, developing, and operating” the campus.

And it was a raging success. In 1952, Glorieta opened a few programs and got 1,400 registrants from 18 states. Over 50 years, thousands of Southern Baptists came to Glorieta. Families pulled up in station wagons. Kids came for summer camp. Church staff arrived for trainings. For many, Glorieta started to feel like a second home—they remembered exactly where they scared the pants off another camper, where they proposed to their girlfriends, where they rededicated their lives to Christ.

“Glorieta had a lot of sentimental and nostalgic value,” Wax said.

But as denominational numbers declined, camp attendance fell. Staff were let go, maintenance was put off, buildings fell into disrepair. By the time LifeWay started looking for a buyer in 2011, they couldn’t give it away.

Priced at $1, LifeWay offered Glorieta to every other SBC entity. When no one wanted it, the property was sold in 2013 to Glorieta 2.0, a group of Christian businessmen and camping professionals.

Some Southern Baptists were furious about the sale, blaming LifeWay for not keeping Glorieta viable. A lawsuit was filed, claiming the sale wasn’t valid because it wasn’t approved by the SBC executive committee.

“The one time I thought might leave LifeWay was when plaintiff of this lawsuit started attacking my family,” Rainer said. “Then I said, ‘This is not worth it, guys.’ But my family said, ‘We’re fine. Don’t quit LifeWay because of us.’”

“To this day we get criticism over Glorieta,” Wilson said. “I saw up close the personal pain caused by the comments Rainer and his family were getting.”

Later, when Rainer made the decision to sell the downtown office building, she knew he’d face pushback again.

“Thom, why are you doing this?” she asked him. “I knew most leaders would say, ‘No way am I touching that. I’ve had years of pain. I’ll leave this for the next leader.’”

Rainer didn’t pause.

“Because it’s the right thing to do,” he told her.

Writing for the Health of the Church

Rainer edited his first book—Evangelism in the 21st Century: The Critical Issues—25 years ago. Since then, he’s authored, co-authored, or edited nearly 30 more—all centered around the growth and health of the church. His 2013 title, I Am A Church Member: Discovering the Attitude that Makes a Difference, has sold more than a million copies. (“He’s up there with Rick Warren as one of the best-selling Christian authors of all time,” Wax said.)

So when Stetzer told Rainer he should write a blog, Rainer said he didn’t have time. He also didn’t want to have to mess with the comments section.

Stetzer told him to turn off the comments.

“He kept pushing and pushing,” Rainer said. “So I started. And some of the early ones were really bad.”

But eventually, “writing blogs became part of my routine,” Rainer said. “We became a seven-day-a-week resource.”

If I was waiting on my ingenuity [to produce content], I’d be sitting at a keyboard staring at a blank screen. Instead, I’m listening.

Rainer’s online platforms get more than 10 million pageviews annually. His podcasts are downloaded more than 1.5 million times a year.

Those blogs turned out to be crucial for gauging what church leaders were struggling with or wondering about. “Through the number of views or open comment stream, they’re telling me where their pain points are or what their needs are,” he said. “If I was waiting on my ingenuity [to produce content], I’d be sitting at a keyboard staring at a blank screen. Instead, I’m listening.”

I Am a Church Member was born that way, from a blog post, dashed off at midnight for a 7 a.m. deadline.

“After seeing the response, I said, ‘Oh my gosh, we have diminished what it means to be part of the body of Christ so much that they’re starving for this,’” Rainer said.

Rainer’s organization Church Answers also grew from those blog posts and podcasts. “I had so many pastors asking me questions that I couldn’t get to them all,” he said. “So I said, ‘Let’s create a 24/7 forum where you can get a question answered anytime, day or night. . . . I don’t ever want to tell a pastor we can’t help him.’”

Long Change in the Right Direction

“Eugene Peterson’s line was ‘long obedience in the same direction,’” Stetzer said. “For Rainer, it was a long change in the same direction. Make changes one at a time, kind of insist on it, and align the company.”

It worked.

“If you knew LifeWay 10 years ago and LifeWay now, you’d say this is a very different world, in a way that I think is remarkably positive,” Stetzer said. “Thom’s greatest legacy would be he just wants to help the church.”

Rainer’s not done helping. One of his heroes of the faith is Caleb, the spy who was keen to charge into the promised land at 40 years old, and who sounded even more fiercely eager at 85 (Josh. 14:6–12).

“As long as I have breath and an ability to serve God, I’m looking forward,” Rainer said. “Hindsight is 20/20, and I know I would’ve done some things differently. But I’m not going to dwell in that world. I’m looking forward.”

Rainer’s retirement plans look like two full-time jobs. “I’m going to do three podcasts, seven-day-a-week blog posts, and continue with Church Answers.”

And any future books he writes? He’ll publish with LifeWay.

“It became an A-level publisher,” he said. “I love publishing with them now.”