In August, Oxford University Press will publish his spiritual biography Woodrow Wilson: Ruling Elder, Spiritual President as part of a new series edited by Timothy Larsen.

He is the author of numerous books, all of which are worth reading if you are interested in the history of evangelicalism:

- Baptists in America: A History, co-authored with Thomas Kidd (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Jesus and Gin: Evangelicals, the Roaring Twenties, and Today’s Culture Wars (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

- Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America (Eerdmans, 2008).

- Evangelical and Fundamentalism: A Documentary Reader (NYU Press, 2008).

- American Evangelicals: A Contemporary History of a Mainstream Religious Movement (Rowman and Littlefield, 2008).

- The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists (Greenwood Press, 2004).

- Uneasy in Babylon: Southern Baptist Conservatives and American Culture (The University of Alabama Press, 2002).

But it’s his first book—God’s Rascal: J. Frank Norris and the Beginnings of Southern Fundamentalism (University Press of Kentucky, 1996)—that I wanted to talk to him about. For it was 90 years ago this week that the rascally J. Frank Norris shot and killed a man in his own church.

Let’s start with an impossibly broad question: Who was J. Frank Norris? More specifically: Where was he from, what was he like, and why does he matter?

I have argued that Norris was the most significant Southern fundamentalist of the first half of the 20th century.

He was born in Alabama in the 1870s and moved to central Texas when he was a child. He grew up in Hubbard, which was also the home of Tris Speaker, one of the greatest major league baseball players of all time. Speaker was about 10 years younger than Norris. Hubbard is about 30 miles from Waco, where Norris attended Baylor University and then Southern Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

His first pastorate was at the McKinney Avenue Baptist Church in Dallas. Then in 1909 he moved to First Baptist Fort Worth where he remained pastor until his death in 1952. From 1935 to 1950 he also pastored simultaneously Temple Baptist Church in Detroit. The combined membership of the two churches was roughly 25,000, which allowed Norris to boast, as he often did, that he had more parishioners under his pastoral care than any other preacher in America.

He was a rabble-rousing fundamentalist, in fact something akin to the stereotype that the media erroneously thinks all fundamentalists fit. He was indicted in the burning of his own church in 1912, again for the infamous murder in 1926, and under suspicion for the burning of his church (again) in 1929. The only legal issue that ever stuck was a libel judgment for which he had to pay a modest sum.

Was Norris a separatist from the get-go, or was this a development in his theology and practice of cooperation (or lack thereof)? What was his role in organizing separatist fundamentalist Baptists in the South?

Norris was a separatist fundamentalist. He spent his career calling people out of the SBC and into his own small, separatist, fundamentalist denomination. With Norris it’s always difficult to tell how much he was driven by theological principle and how much by ego. He loved to fight, and he hated the SBC leaders—George Truett, J. M. Dawson, Louie Newton (that’s Louie, not Huey the Black Panther), and others.

I have spent a good part of my career defending evangelicals and fundamentalists to secular reporters, trying to ween them off the negative stereotypes. But with Norris, the stereotype holds. He was a rascal. He twisted the truth, sometimes in ways that were outright lies, in order to attack his perceived enemies.

I’m no psychologist, but I’m convinced he had a major personality disorder. A history of separatism fundamentalism just published this past year documented cases of sexual harassment and even a possible sexual assault. I never found such evidence, but I find the charges believable. I’ve told many people over the years that I never found compelling evidence that he burned his own church, but I do believe he was capable of it.

All that said, Norris was also an outstanding, indeed mesmerizing preacher, who probably won scores of people to Christ. Chalk that up to God’s grace in using a deeply flawed vessel like Norris.

At the risk of anachronism, would it be fair to call Norris one of America’s first megachurch pastors?

Yes, he was one of the first megachurch pastors, or perhaps we should say megachurches, since he pastored two of them at the same time, in two different states.

How in the world did he pull this off?

He had lieutenants who ran things when he was away. Often he was at neither church, but instead was traveling around doing revivals and making appearances at all manner of national fundamentalist meetings.

By the way, one of these lieutenants was G. Beauchamp Vick in Detroit. Norris eventually persuaded Vick to come to Fort Worth to run the Bible Baptist Seminary. Once in Fort Worth, Vick figured out that Norris was misappropriating funds. When Vick challenged Norris on these and other matters, Norris told Vick essentially that he owned the seminary and could do whatever he wanted. Vick and his group left Norris in 1950 and founded the Baptist Bible College in Springfield, Missouri, and eventually the Baptist Bible Fellowship, which is to this day one of the, if not the, largest fundamentalist denominations in America.

Little more than a year after BBC was formed, a newly converted roughneck from Virginia named Jerry Falwell enrolled. As Falwell said in the 1980s, once he had become famous politically as the founder of the Moral Majority, “I was trained by men who were trained by J. Frank Norris.” Go figure.

So let’s go to July of 1926. Over in California a grand jury was being convened to explore the evidence for Aimee Semple McPherson’s kidnapping or perjury. Over in Gloucester, England, James Innell Packer was born. What was happening in Fort Worth?

In the twenties and thirties (but not the forties, I’ll explain), Norris, like many other fundamentalist and even liberal Protestants, was extremely anti-Catholic. The mayor of Fort Worth—Meacham—was Catholic. Norris began attacking the mayor in his weekly newspaper, The Fundamentalist. The paper ran verbatim print editions of Norris’s weekly sermons (he had a stenographer). In one of these he accused the mayor and his city manager of manipulating a land deal to the advantage of a Catholic church and school in the city. He also said the city manager was the “missing link” and that Meacham was “not fit to be mayor of a hog pen.”

Who was Dexter Elliott Chipps Sr. and how does he enter into the story?

Chipps was a businessman who had moved to Fort Worth from Georgia (or somewhere) years before. He owned a large lumberyard business. He was also Catholic and a strong supporter of the mayor.

So what happened on July 17, 1926?

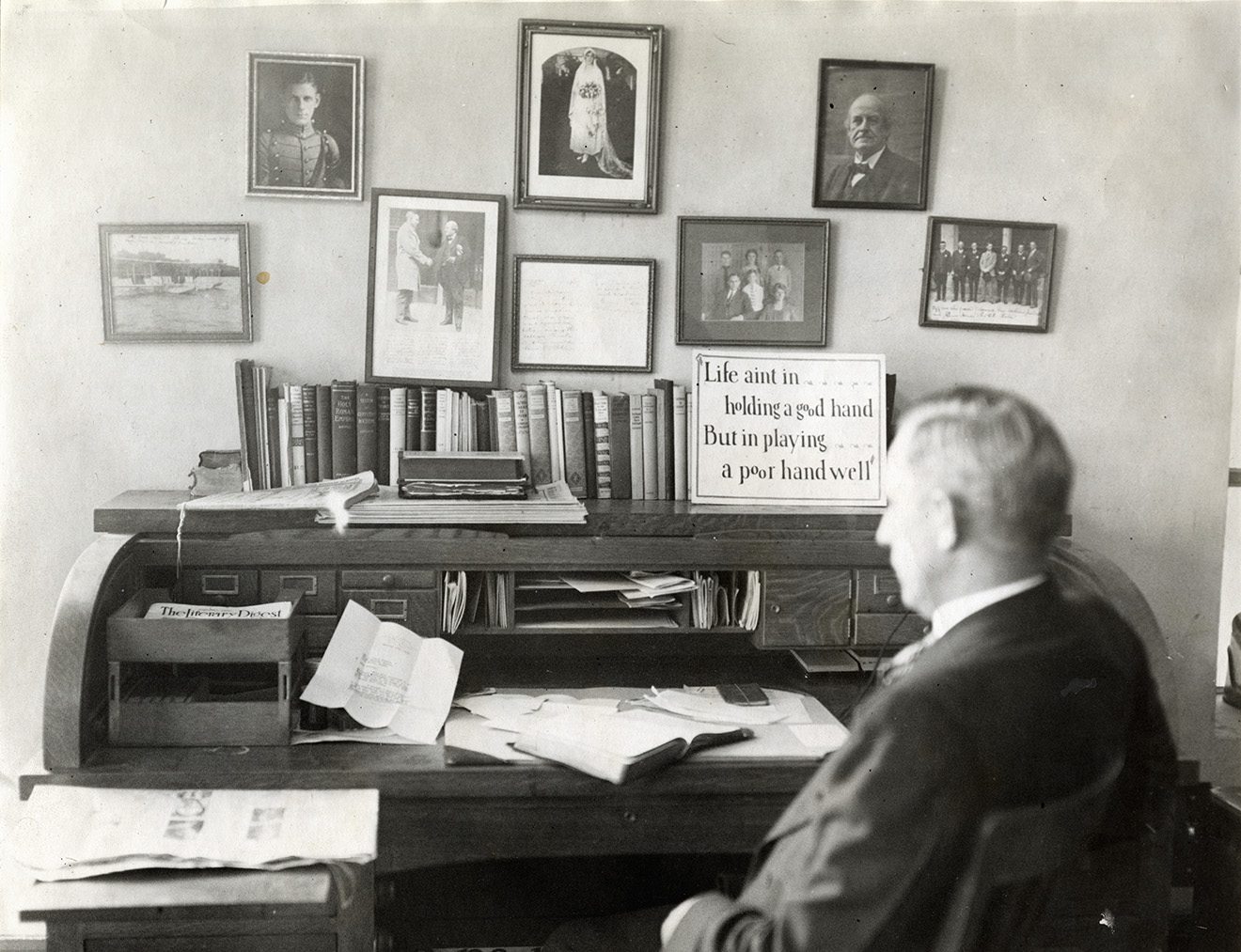

On this day, a Saturday, Chipps called Norris at the First Baptist church office and told him to lay off the mayor. The two apparently exchanged words, as Norris was never one to back down from anything. One thing led to another, and before long Chipps showed up at Norris’s office door. They exchanged more words, and, according to the church business manager who overheard the exchange, Chipps challenged Norris to a fight. Instead, Norris pulled the night watchman’s pistol out of his desk drawer and fired four shots, three of which hit Chipps. As my PhD adviser wrote in the margins of my dissertation draft back in 1990, it was “Goodbye Mr. Chipps.” Norris then called his wife and the police, allegedly saying, “I just killed me a man.”

Norris is released on bail, and Chipps dies at his home. What happened next? Was Norris convicted? Did all of this affect his popularity?

Through a change of venue the trial was moved to Austin, 185 miles to the south. It would have been difficult to find jurors in Fort Worth who were impartial to Norris. You either loved him or hated him, depending on your position in town.

Norris testified in the trial that Chipps had threatened to kill him and that he acted in self defense, which was his plea. This was believable, as other witnesses testified that they had overheard a drunken Chipps say on occasion that he’d kill Norris if he didn’t lay off the mayor. The jury believed Norris, and he was found not guilty. (This is Texas, you know. Kind of an early version of “stand your ground.”)

Norris returned to a packed house celebration in Fort Worth. It appears that First Baptist added perhaps hundreds of members while all this was going on. (Again, go figure.)

Earlier you mentioned Norris’s virulent anti-Catholicism. How did this change in the 1940s?

2. Norris was quite influential politically. The Herbert Hoover campaign of 1928 cited him as more important than anyone in swinging the state of Texas into the Republican column for the first time since Reconstruction. He was invited to and attended Hoover’s inauguration. He corresponded regularly with the top politicians in Texas, including Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and U.S. Senator Tom Connally, and they answered his letters. His newspaper was often filled with political ads and editorials, usually in favor of Republicans in an era when Texas was solidly Democratic. He would love today’s one-party Republican Texas. (No, wait, as soon as Texas went Republican, he would have become an army of one attacking the new establishment!)

3. Norris was the most significant Southern fundamentalist of his era. The problem for Norris is that it was tough to convince Southerners that there was enough theological liberalism to warrant a full scale theological war. This was part of the reason he constantly attacked Southern Baptist leaders, nearly all of whom were orthodox, evangelical Christians. While Norris’s followers numbered in the tens of thousands, he could never get the SBC very concerned about liberalism, because there just wasn’t enough of it to worry about.

4. As Kevin Bauder and Robert Delnay, both products of Regular Baptist fundamentalism themselves, show in their recent book, One in Hope and Doctrine: Origins of Baptist Fundamentalism 1870-1950, Norris is a case study in destructive personality. If Norris’s heirs think I was hard on him, they ain’t seen nothing yet. Bauder and Delnay put it well when they write, “[Fundamentalism] features fools, predators, toadies, hypocrites, power grabbers, and character assassins as well as humble servants, insightful leaders, and heroic warriors” (p. 14). They make it crystal clear which category Norris belongs in. Norris is a case study of the worst aspects of fundamentalism. As I say above, although not in my book, I’m convinced he had at least a personality disorder if not outright mental illness. But he was an outlier, even among those who made a career of fighting militantly for the faith.