Sixty years ago—on Saturday, May 11, 1957—38-year-old Billy Graham arrived in New York City. That evening he held a press conference at the Hotel New Yorker and was interviewed by Walter Cronkite for the CBS Evening News.

It had been eight years since the lanky, telegenic, Southern fundamentalist-evangelical evangelist had burst unto the national scene through his Los Angeles campaign of 1949.

Wednesday, May 15, 1957, would begin the most significant and longest-running campaign of Graham’s storied career.

While there have been no shortage of books and biographies on Graham, only a few rise to the top, including William Martin’s biography (eventually to be updated) and Steven Miller’s Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South.

But the dean of Graham studies right now is Grant Wacker, Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Christian History at Duke Divinity School. His magisterial study of Graham’s career was published in 2014, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation (Harvard University Press). In June 2017, Oxford University Press will publish Billy Graham: American Pilgrim, a fresh collection of essays from historians on various aspects of Graham’s life and ministry, edited by Wacker along with Andrew Finstuen and Anne Blue Wills.

Professor Wacker is currently writing a short narrative biography for Eerdmans entitled, ‘One Soul at a Time’: A Short Life of Billy Graham. The following interview is adapted from his chapter on the 1957 Madison Square Garden crusade.

This was the longest-running and most highly publicized crusade of Graham’s long career. How long was it intended to last, and how long did it end up going?

Originally scheduled to run six weeks, the campaign at the Madison Square Garden in New York City was extended three times.

It started on May 15, 1957, and closed on September 1, Labor Day Eve.

All told, it ran nearly sixteen weeks.

How would you describe Graham’s fame and status when it was all said and done?

If there had been any doubt about Graham’s star status when the crusade began, none lingered by the time it finished. By then Graham ranked as the most famous evangelist in the United States since George Whitefield in the 18th century.

Later one historian of American celebrity preachers would call Graham “the least colorful and most powerful preacher in America.” The least colorful part might be debated, but by 1957 the most powerful part seemed to lie beyond serious debate.

When did the prospect of an event in New York first come onto Graham’s radarscreen?

In 1954 a group of evangelical ministers in the city invited him. He declined because the invitation did not come from a broad enough base. In addition, the prospect of taking his crusades into the Big Apple—with its large Catholic, Jewish, and non-churched population, and its reputation as the command center of American commerce—probably seemed daunting to the still-young evangelist from the rural South.

The following year the Council of Churches of the City of New York, representing more than 1700 congregations and 31 denominations, including Mainline Protestant ones, issued a new invitation. They set their sights on the summer of 1957.

Most people who attended a Graham crusade—or watched one on television—had no idea about all of the behind-the-scenes work that went into preparing for it. Can you tell us a little bit about what had to happen to pull this off?

On a personal level, Graham took the new offer with utmost seriousness. His wife, Ruth Bell Graham, always a strong influence on Billy, urged him to accept. Besides the usual regimen of prayer and preparation of sermons, he jogged the mountains near his house, beefing up his stamina like a prize fighter going into battle.

Extensive preparation had distinguished Graham’s crusades for years, but this one capped them all. It still ranks as the most intricately orchestrated undertaking of his career. Advance men and their families started moving to the city nearly a year before the meetings began. As usual, they launched neighborhood prayer meetings and training sessions for the counselors.

But to an extent not seen before, they cultivated the media by arranging interviews, press conferences, talks with civic groups, and appearances on TV shows for Graham. The organizers’ herculean advertising campaign gave new meaning to the word “mass,” as they blanketed the city with handbills, billboards, bumper stickers, and banners on buses.

What were some of the themes of Graham’s teaching during this marathon crusade?

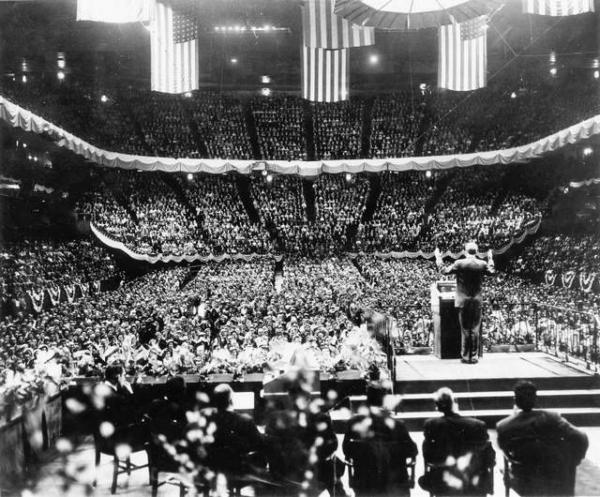

In the opening service, Graham pled with the 18,500 people packing the Garden, “Listen with your soul, tonight; your heart also has ears.” Here as always Graham was preaching for a verdict. But he knew that the verdict—the decision—to choose Christ had to come from an underlying desire to do the right thing. Listening with the soul—with the heart—stirred the desire that produced the decision to stand up, walk to the front, and commit one’s life to Christ. The next morning the New York Times printed the entire sermon, word for word.

What was the response that first night?

Graham’s efforts that night yielded 704 decision cards. He always gave all the credit to God for good results of that sort, but he would have been less than human if he had not taken at least a tiny measure of satisfaction in his own role in it too.

What role did television play in his crusades?

Beginning on June 1st, the BGEA broadcast the Saturday evening services live over the ABC television network. This venture took Graham into millions of homes around the country. Eventually, an estimated 96 million people reported that they had seen at least one of the meetings that way. (After the crusade, they cut back the telecasts of live meetings to once a quarter, to trim costs and not trivialize them by making them routine.) Television close-ups brought him face to face in a way that huge crusade settings and of course radio never could. When color television came along, his sandy blonde hair and, especially, azure blue eyes helped rivet viewers’ attention.

What does Graham’s attire tell us?

Graham knew how to dress the part, first for live audiences in the Garden and then for television audiences around the country.

A decade before, rocketing around the country for Youth for Christ, he had distinguished himself with a flamboyant wardrobe of pastel suits and flashy (sometimes literally flashing) ties. But by the mid-1950s, he looked more like a smartly dressed banker, invariably outfitted in dark suit, subdued ties, wing-tipped black shoes, starched white collars, and the ever present cuff links. One reporter had called him “a walking Arrow collar man.”

If Graham’s dress had gone uptown, so did his style of presentation. If in Los Angeles in 1949 he had preached fast and loud, in New York the speed slowed to what might be called a brisk pace, and the volume dropped. By then he had learned to let the microphone, not his own voice, do the heavy lifting.

When it was all said and done, do we have a reliable way of knowing how many people attended or watched—and how this compares with the other crusades in Graham’s ministry?

The aggregate numbers spoke volumes: nearly 2 million attenders at the regular meetings; 400,000 at miscellaneous and overflow meetings’ and more than 60,000 decision cards turned in.

The statistical records for the New York crusade topped all of his other meetings in the United States, and stood among the top eight of all of them around the world.

The attendance figures likely saw some bloating, since there was no way to control for repeat attenders. But of course this problem compromised the statistics for all of Graham’s four-hundred plus crusades, as well as those for other evangelists.

Who were the people who filled the Garden night after night? Why did they come? (And how do you, as a historian, even determine the answer to such a question since you weren’t there to ask them?)

As before, photographs of the crowds suggest thoroughly middle-class roots. They were a bit less dressed up than they had been in the Los Angeles photos, but so was the rest of America.

Also as before, women predominated, but adolescents and young adults were significantly better represented in New York.

Racial representation was pretty much the same in in both settings: all or almost all white.

As for why they came, the Los Angeles meeting left little evidence, but New York was a different story. From an array of sources—letters, testimonials, interviews—we know that people came for a variety of reasons. For some, going to church was just a good way to pass a summer evening. Others went to see the spectacle, maybe to be able to tell their grandchildren someday they had seen Billy Graham up close. And some went with a premonition that at the end they would walk to the front and try to start their lives all over again.

The New York crusade saw the fully developed use of an outreach program, started at Harringay, called Operation Andrew. This scheme helped bring the crowds in. It encouraged churches in the region to sponsor buses to carry their members to the crusade. The idea was shrewd, for it capitalized on the conviviality of a cross-town or out-of-town bus ride with friends, freedom from the hassles of traffic and parking, and the promise of reserved seating—with one’s friends—once they got there. One feature of Operation Andrew proved particularly successful. Every person was strongly urged to bring a friend, especially a friend who was “unchurched.”

https://youtu.be/X-aTqnFmy14

One of the notable features of this Crusade—which began just months after the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended—was Graham’s desire to address racial justice. Tell us about the background of this development.

Till then, his racial justice efforts were mostly memorable for starting to de-segregate his crusade audiences in 1953 (possibly 1952). In the context of the early 1950s, insisting that he would not tolerate segregated audiences was a momentous and courageous step. One Graham biographer, generally not sympathetic to him, called it his “handsomest hour.” But 1953 was not 1957. “Time makes ancient truth uncouth,” the poet James Russell Lowell had said. Graham knew that he had to do more.

From the beginning at the Garden, Graham saw that his audiences were overwhelmingly white. A few days in, he contacted his black friend Howard Jones, the pastor of a large African-American Christian Missionary Alliance church in Cleveland, and asked what he should do about it. Jones advised, do not wait for blacks to come to you. You need to go to them. The sub-text was clear: you and everything else about your crusade—associates, artists, music, choir, and congregation—present a virtually solid white front. If blacks are hesitant to come, what would you expect?

What did Graham do about this?

Graham responded with four moves.

First, and most controversially, he invited Martin Luther King Jr., to offer a pastoral prayer in the service on July 18. King’s words were affirming, though not ringing, and the same could be said for Graham’s follow-up comments. But given the prejudices of the age, the wonder is not that the prayer and follow-up were less than resounding but that they happened at all. Afterward Graham received searing criticism from white segregationists.

Second, Graham took the crusade out of the white precincts of the Garden and into preponderantly African American sections of the city in Harlem and Brooklyn. Facilitated by Jones, he preached to church audiences of thousands in both places. In Brooklyn he acknowledged, perhaps for the first time publically, that discrimination required anti-segregation legislation as well as Christian love.

Third, Graham and crusade boss Cliff Barrows diversified the roster of guest artists by featuring black blues soloist Ethel Waters, singing her signature song, “His Eye is on the Sparrow,” backed by the mass choir of 3,000 voices. Graham also appeared on The Steve Allen Show with the African American actress and singer Pearl Bailey, who promised to attend the meetings. At Graham’s invitation, Jones joined the Graham team in New York and sat on the platform. The solidly white image of the Graham revival was slowly changing.

Finally, Graham’s least dramatic but in the long run most important move was to add Jones and, later, African Canadian evangelist Dr. Ralph S. Bell to the roster of permanent associate evangelists. Their recurring presence on the stage and behind the pulpit sent powerful signals.

The Graham team took advantage of a number of “public relations opportunities” offered by New York. (The critics labeled them “publicity stunts.”) What role did these play in the crusade and its legacy?

Graham deftly exploited these opportunities, knowing how to command the media’s and the public’s attention. The most notable example was Graham’s decision to move the meeting to Yankee Stadium on July 20, the day that he had earlier targeted as the closing night. With 100,000 souls jammed into the stadium’s bleachers, and another 20,000 gathered outside the gates, Graham drew the largest crowd in the stadium’s history since Joe Louis knocked out Max Baer in 1935. Reporters noticed and drew parallels between Graham’s bouts with the devil and Louis’s with Baer.

Though Graham had no way of knowing in advance, everyone sweltered in the heat, 96 outside and 105 on the stage, one of the hottest days of the year. The weather alone made it stick in memory.

What Graham did know in advance was that Vice-President Richard Nixon would attend and address the faithful from the pulpit. Nixon brought greetings from President Eisenhower, whom he called “a good friend of Dr. Graham.” Nixon added that one of the reasons for the nation’s progress was the “deep and abiding faith” of its people.

Nixon made another comment that revealed worlds within worlds about the power of Graham’s attraction to millions of people: his humility. Walking into the stadium with Graham, Nixon complimented him on the size of the crowd. Graham replied, “I didn’t fill the stadium, God did.’”

Nixon’s visit marked two firsts: (1) the first time a sitting vice-president would participate in a Graham meeting, and (2) the first time Graham would mix the gospel with partisan politics in such an unapologetic way.

[JT: At the 34:00 mark, you can watch Graham introduce Nixon, who speaks for about 10 minutes, from 36:00 to 46:00.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OqyWsoBrnsA

Setting aside whatever influences on the culture this crusade might have had, historians recognize that one of the most significant internal legacies from this summer was Graham’s decision about partnering with modernists, moderates, and mainliners.

The New York crusade embodied and portended one of the most important strategic decisions of Graham’s entire life. He determined that he would work with anyone who would work with him if (1) they accepted the deity of Christ and if (2) they did not ask him to change his message.

In practice he quietly overlooked the “deity of Christ” provision. He accepted the help mainline of Protestants who probably would have the affirmed the divinity but not necessarily the deity of Christ, and of Jews, who found his emphasis on God, patriotism, and decency appealing.

But the second provision—“if they do not expect me to change my message”—proved absolutely non-negotiable. There is no evidence anyone tried.

Inclusiveness worked—on the whole. As I noted earlier, the invitation to New York came from a majority of the churches, evangelical and mainline. It is hard to generalize about Catholics, but signs abound that thousands of ordinary believers and many members of the Catholic clergy supported him. Some Jews, too.

That being said, fundamentalists relentlessly opposed Graham’s effort in New York and, from then, pretty much everywhere else. By working with so-called liberals and Catholics, they reasoned, he had sacrificed doctrine for success, and the price was too high. Their opposition could be called “the bitterness of disillusioned love.” In their eyes, Graham had once been one of them, but he had left the family, never to return.

The diversity was not only religious but also included men and women from a variety of occupations and social levels. The crusade was sponsored and undoubtedly partly funded by leading figures in the business community, such as George Champion, vice president (soon president) of Chase Manhattan Bank, one of the largest in the nation. The nightly meetings featured a retinue of testimonials from prominent entertainers, politicians, and military men. Anecdotal evidence suggests that thousands of ordinary people—more often readers of the New York Post than the New York Times—talked about the meetings on the subways and in street corner diners.

Tell us about the closing night.

On the closing night, 125,000 souls, crowded under the stars in Times Square and surrounding streets. Crusade organizers staged the event for September 1, the night before the Labor Day holiday, when many people would be off work. And a night that symbolized the closing of one season and the opening of another.

It is easy to believe that for many of the thousands who turned in decision cards that evening, it also marked the end of one season of their lives and the opening of another.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQnlH3JNJ-g

For an outstanding online exhibit on the 1957 campaign, including posters, film, and oral history, see the Billy Graham Center Archives at Wheaton College here and here.