On July 13, 2024, former President Donald Trump was very nearly assassinated on live television by a sniper’s bullet.

Historian Niall Ferguson writes:

A slight gust of wind, a tremor of the assassin’s hand, an unexpected move by the former president—for whatever tiny reason, Trump lived to fight another day.

As the editors of National Review wrote:

If the bullet that wounded Trump had traveled a slightly different path, we would have witnessed earlier this evening one of the most horrifying events in American history. It would have deepened the sense of crisis gripping our country and would have had unforeseeable consequences, none of them good. Sometimes the course of history depends on margins just that small.

Whether it was a bad wind estimate or Trump’s turn of the head at the last second, or (most likely) both, the former President—and current Presidential frontrunner—came within inches of his life.

Several presidents, former presidents, and presidential candidates in U.S. history have been shot. But Abraham Lincoln was the first, suffering a mortal bullet wound to his brain at the age of 54 on the evening of Good Friday in 1865, just days after the end of the Civil War. Nearly nine hours later, he was dead. In a forthcoming book with Oxford University Press, tentatively titled “Our Beloved Martyred President”: The Assassination and Sacred Legacy of Abraham Lincoln, historian James P. Byrd will look at the sermons that were preached in the United States that Easter Sunday and beyond.

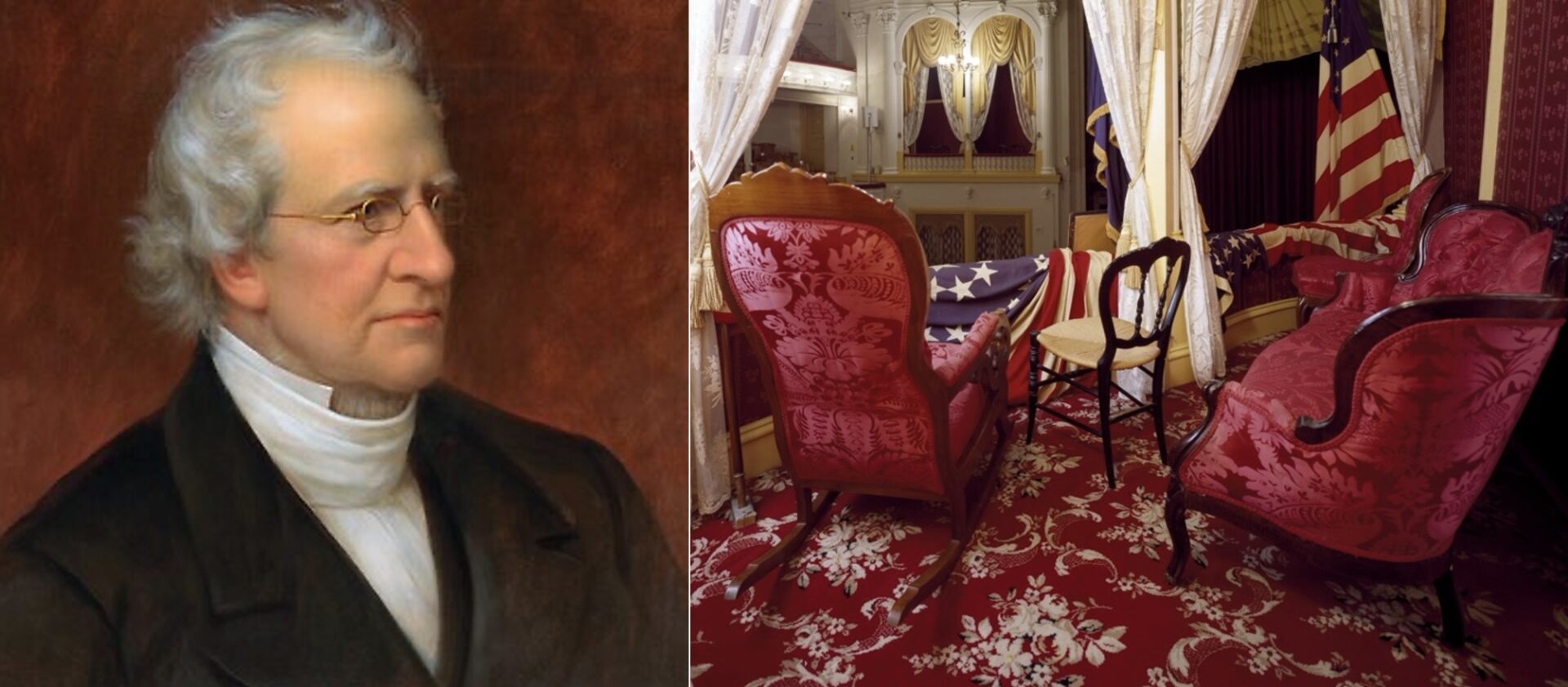

After the assassination, theologian Charles Hodge, principal of Princeton Theological Seminary, published a nearly 10,000-word, 23-page essay on “President Lincoln” in The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review (vol. 37, issue 3 [1865]: 435–58).

It is a fascinating glimpse into the thinking of a Reformed theologian who was the leading public intellectual of his day, reflecting on the providence of God in light of this perplexing national tragedy.

Here are some notes on what Hodge wrote.

Four Assumptions Behind the Scriptural Doctrine of Providence

Skipping any prefatory comments, Hodge begins by explaining four assumptions behind the scriptural doctrine of divine providence:

- The external world really exists.

- Secondary causes are efficient.

- Apart from supernatural events, all events in nature or history have their proximate and adequate causes in the agency and properties of created substances (spiritual or material).

- God is not a mere spectator of the world, nor is God the only efficient cause. Rather, God “is everywhere present, upholding all things by the word of his power, and controlling, guiding, and directing the action of second causes, so that all events occur according to the counsel of his will.”

Hodge insists that

- nothing happens by necessity and

- nothing happens by chance.

According to Hodge, God governs

- free agents with certainty without destroying their liberty, and

- material causes without superseding their efficiency.

Every great event, therefore, is to be viewed as

- the effect of natural causes, and

- a design and result of God’s providence.

The Challenges of Interpreting Providence

Hodge urges humility and caution when it comes to interpreting providence, because it often involves great difficulty and responsibility.

When it comes to the design of events, he says that they could be in one of three categories:

- perfectly clear,

- doubtful, or

- for the present inscrutable.

“We have a right to infer,” he says, “that the actual consequences of any event, whether great or small, are its designed consequences.”

How do we know whether God intends judgment or mercy to those affected by them? He says it must be determined partly by three things:

- their nature,

- their attendant circumstances, and

- the course of subsequent events.

He writes:

No Christian can look upon the events of the last four years without being deeply impressed with the conviction that they have been ordered by God to produce great and lasting changes in the state of the country, and probably of the world. Few periods of equal extent in the history of our race are likely to prove more influential in controlling the destinies of men. Standing, as we now do, at the close of one stage at least of this great epoch, it becomes us to look back and to look around us, that we may in some measure understand what God has wrought.

Chattel Slavery Was the Cause of the War, and God Was Displeased

Despite the claims of Southern partisans, Hodge wrote, “the conviction is almost universal, both at home and abroad, that the great design and desire of the authors of the late rebellion were the perpetuation and extension of the system of African slavery.”

It cannot really be doubted that this was “a most unrighteous end.” To say all forms of slaveholding is evil would be an “unscriptural extreme,” but two points are undeniable:

- However it may be right in certain states of society and for the time being to hold a class of men in the condition of involuntary bondage, any effort to keep any such class in a state of inferiority or degradation, in order to perpetuate slavery, is a great crime against God and man; and

- The slave laws of the South, being evidently designed to accomplish that end, were unscriptural, immoral, and in the highest degree cruel and unjust. It is self-evident that only an inferior race can permanently be held in slavery, and it is therefore unavoidable that the effort to perpetuate slavery involves the necessity of the perpetual degradation of a class of our fellow-men. Such was the design and effect of the laws

He lists the design and effects of laws such as those that

- forbade slaves to be taught to read or write;

- prohibited their holding property;

- made it a legal axiom that slaves cannot marry;

- authorized the separation of parents and children, and of those living as husbands and wives.

No wonder, then, the Lord was displeased with this great sin: “It could not be that an offence so great as the indefinite perpetuity of a system so fraught with evil, and the avowal of the purpose not only to perpetuate but to extend it, could long continue without provoking the Divine displeasure.”

The Mystery of Providence

Hodge’s extensive essay works through the consequences of the war, including the rise in the country’s religious spirit:

More prayer has probably been offered to God during the past years, from sincere hearts, than in any ten years of the previous history of our country.

Never before have there been such frequent, open, and devout recognitions of the authority of God as the Ruler of nations, and of Jesus Christ, his Son, as the Saviour of the world, by our public men, as during the progress of this terrible war.

He goes into quite some detail about why Lincoln’s death is a national sorrow, examining the President’s character and public services, as well as the principles of his administration.

But most relevant for our purposes, as we think about providence and tragedy, is the category of mystery. Not all of God’s purposes behind a particular events are unknown, but some are.

We cannot see the reason for it, nor conjecture the end it is designed to accomplish.

We can see the reason for many of our recent national disasters. Had we been as overwhelmingly successful at the beginning as we have been at the close of the war, none of the great results to which we just referred would have followed. Slavery would not have been overthrown, and nationality would not have been vitalized; our power would not have been developed, and our stand among the nations of the earth would have been very different from what it is at present.

But why Mr. Lincoln should have been murdered just when he was most needed, most loved, and most trusted, is more than any man can tell.

God however is wont to move in a mysterious way. [An allusion to William Cowper’s 1773 hymn.]

Hodge gives examples from the early church through the Reformation of evil deeds that are difficult to understand: “These are things we cannot, even after the lapse of centuries, understand.”

There is a use in mystery.

What are we, that we should pretend to understand the Almighty unto perfection, or that we should assume to trace the ways of him whose footsteps are in the great deep?

It is good for us to be called upon to trust in God when clouds and darkness are round about him.

It makes us feel our own ignorance and impotency, and calls into exercise the highest attributes of our Christian nature.

It is therefore doubtless a beneficent dispensation which calls upon this great nation to stand silent before God, and say,

It is the Lord, let him do what seemeth good in his sight. [Cf. 1 Sam. 3:18]

The Judge of all the earth must do right. [Cf. Gen. 18:25]

Most Americans won’t wrestle deeply with the question of providence, not least because the former president and current presidential candidate survived the assassination attempt. Lost sometimes in the discussion about God’s providence in such an event is that even though former President Trump survived, Corey Comperatore lost his life. A churchgoing Christian and a firefighter, he died protecting his wife and daughter from the assassin’s bullet. And two others were critically wounded.

The lessons from such events remain the same today as what Hodge urged upon the readers of his day:

The fact that all things are ordered by God, and must work out his wise designs, does not change the nature of afflictions, or modify the duties which flow from them as afflictions.

When God brings any great calamity upon us, he means us to feel it.

He designs that we should be humbled, that we should mourn and pray.

It is thus that he makes our trials the means of good.

If we harden our hearts under his chastising hand; if we refuse to mourn and to humble ourselves in his sight, our afflictions become punishments, and work out for us only evil, however they may minister to the good of others.

Humility. Mourning. Prayer. These are always the appropriate responses in the light of evildoing.