A friend recently asked just how bad this moment was in American history. “Before January 6,” I answered, “I might have put it in the top 10-15 most tense moments in American history. Now it might be approaching top 5 status.”

My friend actually seemed encouraged by that answer. As bad as things have gotten with the riot/insurrection incited by the president, and his repeated efforts (starting well before November) to undermine the American election and the peaceful transfer of power, we have been in spots like this before.

Here are five really bad moments in American history that were as bad or worse than what we’re dealing with now:

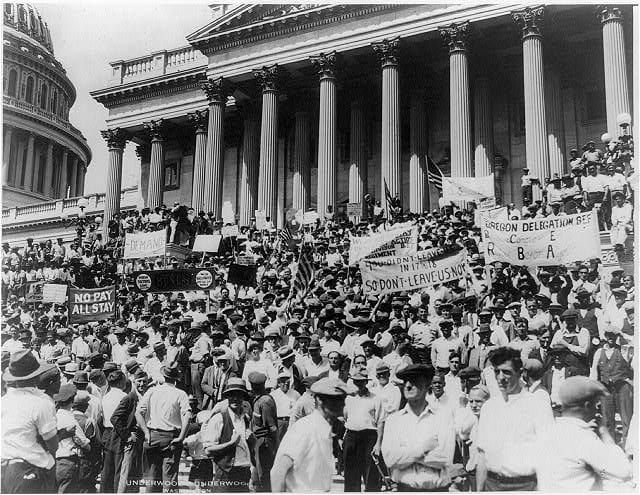

–The early years of the Great Depression and the crackdown on the “Bonus Army”: “The incident that best illustrated the breakdown of the relationship between many of the American people and the Hoover administration was the federal crackdown on the “Bonus Army” of veterans in Washington, DC, in 1932. Tens of thousands of out-of-work World War I veterans had descended upon Washington in the spring of 1932 to demand early payment of a cash “bonus” that Congress had authorized to be paid to them. The bonus was not due until 1945, but the veterans argued that given the dire conditions, Congress should issue the payments early. Congress declined. Many of the Bonus Army’s members left the capital city, but a few thousand stayed in Washington. District police tried to remove them from their encampment in July, but some of the veterans refused to budge. In the ensuing violence, two of the protestors were shot and killed.

President Hoover summoned federal soldiers to assist the police confronting the Bonus Army. Tanks and infantrymen went in, led by Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, who would later become famous for his roles in World War II and the Korean War. (MacArthur’s assistants in 1932 included future World War II generals George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would also become US president in 1953.) MacArthur’s forces used tear gas to evict the marchers from their camp, and then they burned down the protestors’ ramshackle tent village. MacArthur’s tactics had clearly exceeded Hoover’s intentions, yet Hoover did not discipline him. MacArthur regarded the marchers as a “mob . . . animated by the essence of revolution,” who threatened the stability of the federal government. The image of the administration turning the force of government against impoverished veterans was one of the last, and worst, public relations disasters for President Hoover.” [descriptions taken from my book American History, B&H Academic]

–The Nullification Crisis (1832-33): “Shortly after Andrew Jackson defeated his old enemy Henry Clay in the 1832 presidential election, the ongoing crisis over tariffs and nullification went to a new level of severity. Jackson had tried to moderate tariff policy, but in 1832 Congress passed another tariff that kept duties high on British textiles. Again, this hurt southern cotton producers. Following through on John C. Calhoun’s earlier threats, the state of South Carolina held a nullification convention in late 1832, declaring the 1828 and 1832 tariffs “null, void, and no law.” The state would not allow federal authorities to collect the tariff in South Carolina.

Jackson had been sympathetic to southerners’ grievances against the tariff, but now he was outraged. As president, he saw nullification as a threat to the Union itself, and he believed that he had no greater responsibility than to preserve the Union. He declared nullification, or “the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, [as] incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed.” The nullifiers’ ultimate goal, he thundered, was disunion, and disunion was “TREASON.” Jackson began planning to invade South Carolina, and threatened to hang Calhoun if the crisis led to civil war. When Jackson sent in federal forces to protect the Charleston customs house where tariffs were collected, Governor Robert Hayne called up the South Carolina militia.

In 1833, war loomed as Jackson asked Congress to pass the Force Bill, which authorized military intervention to make South Carolina comply with the tariff. But Jackson and many congressmen still hoped they could avert bloodshed. So Henry Clay worked out a compromise measure on the tariff, which lowered duties (though not as much as the nullifiers had hoped) the same day, March 1, 1833, that Congress passed the Force Bill. Calhoun reluctantly backed down, and South Carolina rescinded its ordinance of nullification. To make a point, however, they nullified the Force Bill. But Jackson no longer intended to take military action.”

–The Sedition Act (1798): In the context of the Quasi-War with France, “Many Federalists argued that the growing number of immigrants in the United States was destabilizing the nation, and fueling the growth of the party of Jefferson. These fears led the Federalist-controlled Congress, at Adams’s behest, to craft the Alien and Sedition Acts, the most notorious legislation of the 1790s. The Alien Acts promised to give the president expanded powers to detain and deport foreigners, if war did break out. A new naturalization policy required immigrants to wait fourteen years to apply for US citizenship. This was clearly designed to delay the voting eligibility of the immigrants, who tended to prefer the Democratic-Republicans.

The most ominous of the measures, however, was the Sedition Act. This act represented the first great challenge to the First Amendment to the Constitution, and its guarantees of free speech and a free press. It led Jefferson to call the 1798 furor the “reign of witches.” The Sedition Act made it a crime to “write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States.” This was not just an idle threat. The government prosecuted twenty-five people for violating the Sedition Act, all of them Democratic-Republicans. One Vermont congressman spent four months in jail for writing about the “ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice” of the Adams administration.

The Sedition Act reminds us that the Constitution may guarantee basic rights and liberties, but maintaining or securing those freedoms often requires vigilance by the people themselves. Democratic-Republicans suggested extraordinary measures to respond to the Sedition Act, with some radicals proposing that secession by the southern states might become necessary. Jefferson and Madison wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, respectively, making a strong case for the states’ ability to resist the national government.”

-The War of 1812 and the burning of Washington, DC: One of the main theaters “of the War of 1812 was the mid-Atlantic coast. The British navy controlled much of the Chesapeake Bay region, assisted in part by runaway slaves. As they had during the American Revolution, some British commanders promised to grant slaves freedom if they left their masters and fought on the British side of the war. More than 3,000 slaves from Virginia and Maryland took them up on this offer.

In 1814, the British seized upon American vulnerability on the mid-Atlantic coast to invade Maryland and to destroy Washington, DC. Although the capital remained small during the James Madison administration, it was still humiliating for the British to enter the city largely unchallenged in August. James and Dolley Madison escaped the White House just before the British troops arrived. The Madisons managed to save a portrait of George Washington and a copy of the Declaration of Independence, but the British burned the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings. [This episode was the last major assault on the capitol building until Jan. 6, 2021.]

The British then turned north, descending upon the burgeoning city of Baltimore, Maryland. In September 1814, they bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor, but the American defenders would not crack. Baltimore was saved. A Baltimore lawyer named Francis Scott Key had watched the bombardment and was moved to write a poem, “The Star-Spangled Banner” (or “Defense of Fort McHenry”) when he saw the American flag still flying over the fort at daylight.”

Obviously, the crisis leading to the Civil War “takes the cake” for the most volatile and violent series of political episodes in American history. By 1850, senators had already engaged in violent confrontations in Congress, and in 1856, Senator Charles Sumner was nearly beaten to death in the Senate chamber by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks. Then in 1859, the fanatical abolitionist John Brown captured the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, [West] Virginia. This made the stakes of 1860 the highest they’ve ever been in American history:

“The 1860 election was an exceptional one in the history of American politics. The northern sectional candidate Lincoln depended on deep divisions in national politics to have any hope of success. Often in American elections, a major presidential candidate has received few or no electoral votes from a particular region of the country. But Lincoln was different. He literally got no popular support in most of the South. In ten slave states, he was not even on the ballot. In Kentucky and Virginia, where Lincoln did appear on the ballot, he only received about 1 percent of the vote.

John Breckenridge, the southern Democratic candidate, and John Bell, the “Constitutional Union” nominee, likewise received virtually no popular support in parts of the North. Stephen Douglas was the only one of the four candidates to receive a respectable level of support in all areas of the nation (although he only got 12 percent of the southern vote). Broad popular support was not the issue, however. Constitutionally, what a presidential candidate needed was support in a sufficient number of states to win the Electoral College. In the end, Lincoln won the election by taking all of the free states except for New Jersey, which he split with Stephen Douglas. That gave Lincoln a strong majority in the Electoral College, though he garnered less than 40 percent of the popular vote nationally.

In the fall of 1860, white southerners, especially the Fire-Eaters, began to see the scenario unfold that could put Lincoln into the White House and made dire predictions about what Republican victory would mean. In the months before the election, the South trembled with rumors of slave insurrections and John Brown–type conspiracies. One Methodist periodical in Texas ran a column claiming that the Republicans and abolitionists intended to “deluge” the slave states in “blood and flame . . . and force their fair daughters into the embrace of buck negroes for wives.” A Georgia newspaper warned, “Let the consequences be what they may—whether the Potomac is crimsoned in human gore, and Pennsylvania Avenue is paved ten fathoms deep with mangled bodies . . . the South will never submit to such humiliation and degradation as the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln.”