In 1843, a 21-year-old Dartmouth student named Mellen Chamberlain was doing research on the American War for Independence.

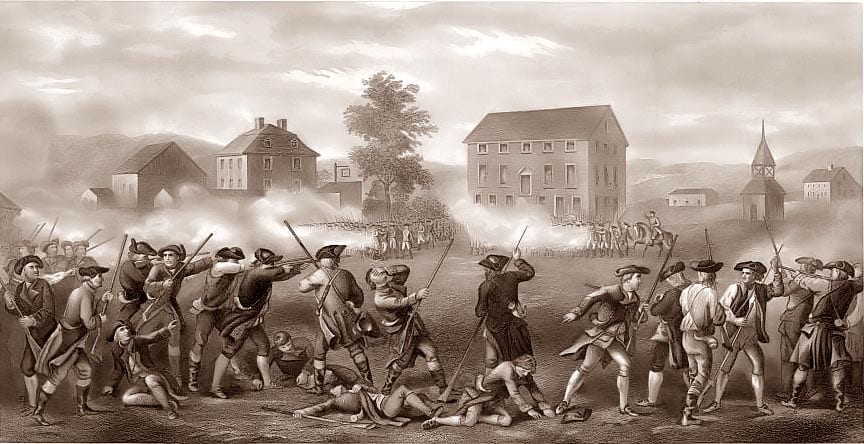

He had the opportunity to interview a survivor of the initial battles of Lexington and Concord, 91-year-old Captain Levi Preston of Danvers.

The young scholar wanted to know the cause behind his involvement with the war.

David Hackett Fischer records their exchange:

“Captain Preston,” he asked, “what made you go to the Concord fight?”

“What did I go for?” the old man replied, subtly rephrasing the historian’s question to drain away its determinism.

The interviewer tried again, “. . . Were you oppressed by the Stamp Act?”

“I never saw any stamps,” Preston answered, “and I always understood that none were sold.”

“Well, what about the tea tax?”

“Tea tax? I never drank a drop of the stuff. The boys threw it all overboard.”

“I suppose you had been reading Harrington, Sidney, and Locke about the eternal principle of liberty?”

“I never heard of these men. The only books we had were the Bible, the Catechism, Watts’s Psalms, and hymns and the almanacs.”

“Well, then, what was the matter?”

“Young man, what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had been free, and we meant to be free always. They didn’t mean we should.”

[For more details, see, “Why Captain Levi Preston Fought: An Interview with One of the Survivors of the Revolution by Hon. Mellen Chamberlain of Chelsea,” Danvers Historical Collections 8 (1920): 68–70.]

This anecdote, of course, doesn’t mean that journalists and historians should stop asking complex questions about the past or tracing the long tail of influences leading up to an action. Memories are fallible; they can be simplistic, and good investigations of the past go beyond what any one individual thinks and to observe trends, patterns, and wider swaths of thought.

But it’s still a fascinating example of someone having a narrative, based on reading, and how different it looks if they were able to interview the actual participants.

Historical causation is notoriously complex. Yet sometimes we forget that a historical actor’s motivation can be surprisingly simple. As those interested in correctly interpreting the past, we should never stop our investigation with the self-perception or motivation of those involved in the events. But we should often start there.

All of this reminds me of a quote from the conservative political and cultural commentator Jonah Goldberg:

The car and the birth-control pill have—for good and ill—done more to overturn settled institutions and customs than Nietzsche or Marx ever could.

But pills and automobiles are hard to argue with, so like drunks searching for their car keys under the street lamp because that’s where the light is good, intellectuals focus on the stuff they can argue with.