The book of Job is not answering a theoretical question about why good people suffer. It is answering a practical question: When good people suffer, what does God want from them? The answer is, he wants our trust.

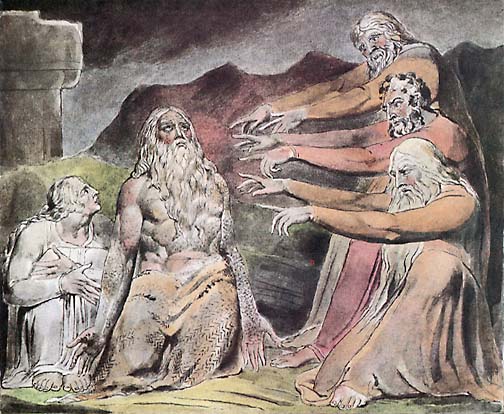

The book is driven by tensions. One, Job really was a good man (1:1, 8; 2:3). He didn’t deserve what he got. Two, neither Job nor his friends ever saw the conflict going on between God and Satan, but his friends made the mistake of thinking they were competent to judge. Three, his friends interpreted his sufferings in moralistic, overly-tidy, accusing categories (4:7-8). Thus, they did not serve Job but only intensified his sufferings further. Four, Job refused to give in either to his own despair or to their cruel insinuations. He kept looking to God, he held on, and God eventually showed up (38:1-42:17).

Two observations.

One, even personal suffering has a social dimension, as others look on and inevitably form opinions. Suffering brings temptation both to the sufferer and to the observer. The sufferer is tempted to give up on God. The observer is tempted to point his finger at the sufferer with smug, self-serving thoughts and words: “This is all your own fault, of course. If you’d just own up, everything would start getting better.” The fallacy here is to assume that we live in a universe ruled by the simple laws of crime and punishment. Our minds dredge up these thoughts not really because we are confident in ourselves but because we are uneasy about ourselves and therefore threatened by the suffering of another: “If it’s happening to Job, it might catch up to me too.” So we cling to the illusory feeling of control by reinforcing our own self-image of moral superiority. We try, by sheer force of assertion, to re-order the moral universe in a way reassuring to our prejudices. The book of Job teaches a more honest and humble way. When we observe someone suffering, we too should trust God and sympathize with the sufferer rather than off-load our own guilty anxieties by dumping on the sufferer.

Two, when we ourselves suffer in ways that defy easy explanation, God wants us to trust him more deeply than we ever have before. Job eventually settles into a profound place where, without answers to his questions, he trusts in the omnicompetence of God: “I know that you can do all things” (42:2). What God can do is more important than how God explains himself. What if he did tell us every mystery right now? Would we be satisfied? Would we say, “Oh, I see. Here I have your explanation for it all. That really makes everything okay now”? I doubt it. An explanation is a wonderful thing, so far as it goes. But it is an intellectual thing. It cannot touch our core being, where the anguish in fact has taken up its deepest residence. Far better to leave it all with God, as our faith deepens from questioning to waiting. We don’t live by explanations; we live by faith.

“I know whom I have believed, and I am convinced that he is able.” 2 Timothy 1:12