Over the past few weeks, I’ve been enjoying National Review’s “Great Books” podcast. Every episode focuses on a classic book that has shaped our society. After hearing the episode on Witness by Whittaker Chambers, I bought the book and devoured it in a few days, finding it to be every bit as fascinating as the podcast had indicated. I also picked up Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, which, despite being on plenty of middle- and high-school reading lists, was passed over at the Christian school I attended (most likely for its occasional swearing).

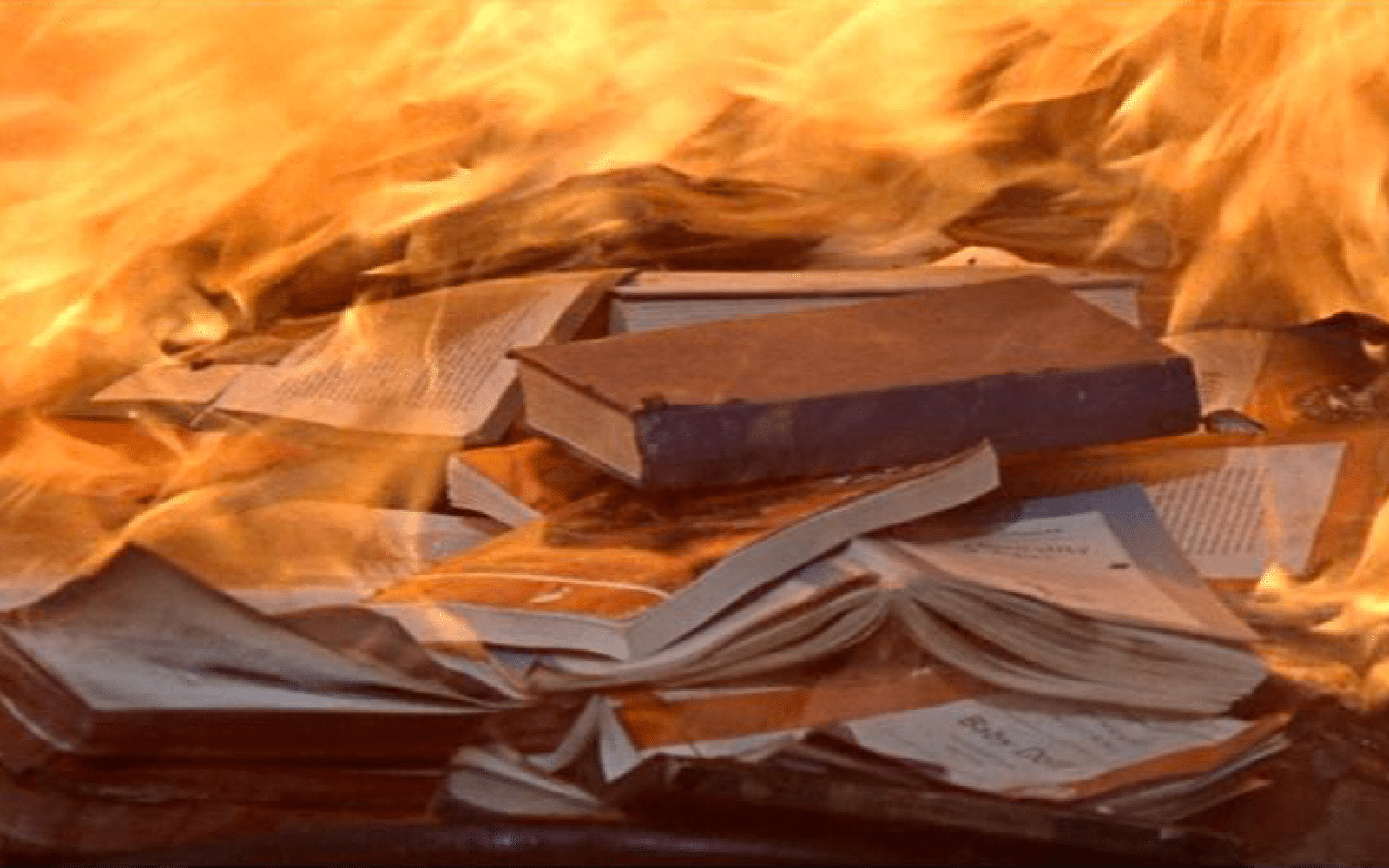

When I finished reading Fahrenheit 451, I saw that HBO had just released a film version of the dystopian thriller, starring Michael B. Jordan and Michael Shannon. When Bradbury wrote this book, at the dawn of the television era, he envisioned a future world where entertainment becomes the solution to the world’s pain and suffering. Firemen don’t put out fires; they start them, and books—dangerous for their ideas that lead to debate, conflict, and suffering—are banned and burned. The title refers to the temperature at which books catch fire.

Writing for The Federalist, Georgi Boorman claims the new movie is better than the book; its adjustments to the storyline have improved on the original characters. I disagree, but not because I’m giving into the typical grumpiness expressed by literature fans when their favorite books are altered for a new medium. I have no problem with films that take dramatic license with original sources. When it comes to Fahrenheit 451, my question is not “Does this movie follow the book?” but “Does this movie capture the heart of the story?” And, unfortunately, that’s where I believe the new adaptation fails.

To be sure, many of the changes HBO made were smart, mostly related to updating the technological aspects of the original. In the movie, we encounter an eerie ever-watching computer eye named Yuxie (similar to Alexa). The destruction of information and enforcement of censorship happens not only through book bonfires but also through the smashing of hard drives. It was also a good decision to leave out what the book describes as a mechanical hound that pursues fugitives.

But the movie introduces major changes in the two most important female characters in Bradbury’s work.

First, the modern adaptation removes Guy Montag’s wife, Mildred, from the story altogether. I understand why the moviemakers thought the story would be better off without Mildred. She’s a pathetic character, addicted to her screens and medicines, escaping into a world of unhappy pleasure, yet satisfied with her vices and the stories she accepts as true. Perhaps the filmmakers believed that it was better to show the fragmentation of society by having Montag be single instead of married. Boorman describes Mildred as “insufferable” and writes:

Of course, she had both an illustrative purpose in showing how much misery constant media immersion can generate and a mechanical purpose to further the plot by ratting out her husband. Still, she’s a character a producer might think twice before bringing to the screen if he could avoid it.

The second significant change concerns Clarisse, the young woman who in the book appears briefly at the beginning of the story. The relationship between Guy and Mildred is so strained and superficial that neither one can even remember when they first met. But Guy’s first meeting with Clarisse kicks off the story and awakens a longing he never knew he had. The movie expands her role, portraying her as an older, rough-edged undercover operative who becomes a love interest for Montag. Boorman applauds this change as an improvement:

In Bradbury’s original tale, Clarisse was just there to further the plot, like Mildred. She’s a teenager who dies in a car crash early in the story, and it is not clear at all that Montag has fallen in love with her. Her death is sad, but not tragic.

Those are the two most significant changes, and both affect the story because they reduce the internal tension Montag feels as he goes from taking pleasure in burning books to bravely resisting totalitarianism in order to rescue our human inheritance. The reason the contrast between Mildred and Guy matters to the plot, and the reason why the contrast between Mildred and Clarisse remains indispensable to the drama, is because these characters show us what it means to be either fully alive or sensually deadened, aspiring to human greatness or succumbing to superficial pleasures.

At its heart, Fahrenheit 451 is not about censorship and book-banning; it’s about history and book-loving. In Bradbury’s version, Montag finds Clarisse compelling, not due to a spark of romance, but to her spark of wonder at the world around her. Montag is drawn not to her beauty or bravery, but to her interestedness and curiosity. She knows depths of happiness and sadness that he has never experienced. She’s alive to the world in a way that he is not. And what sets Montag on the journey that forms the narrative arc of the book is his encounter with people who are fully human, throbbing with passion and knowledge and debate—in contrast to the dull and isolated world of shallow friendships, where everyone is addicted to screens and drugs.

The book shows us a man who stashes away books in secret places, who experiences genuine mourning when Clarisse and her family disappear, and who vacillates back and forth between conformity and rebellion. The movie loses the drama of Montag’s journey in exchange for more action from the underground resistance.

Wonder at the world and gratitude for the treasures of human history—this is the light that pierces Bradbury’s dark, dystopian tale. A few rays of that light make it into the new film version, but because Mildred is excised and Clarisse is reinvented, the filmmakers rely on weaker elements to move Montag along in his development from destroyer to preserver of books.

The movie still accomplishes something that Bradbury intended: it serves as a warning of how we can amuse ourselves to death, or gain the technological world and lose our souls. “Totalitarianism and censorship are bad,” it says. But it skips over the deeper magic of Bradbury’s tale, which says, “History and its treasures are good,” while showing us not only what people awakened to the wonders of our civilizational inheritance fight against, but also what kind of world they fight for.