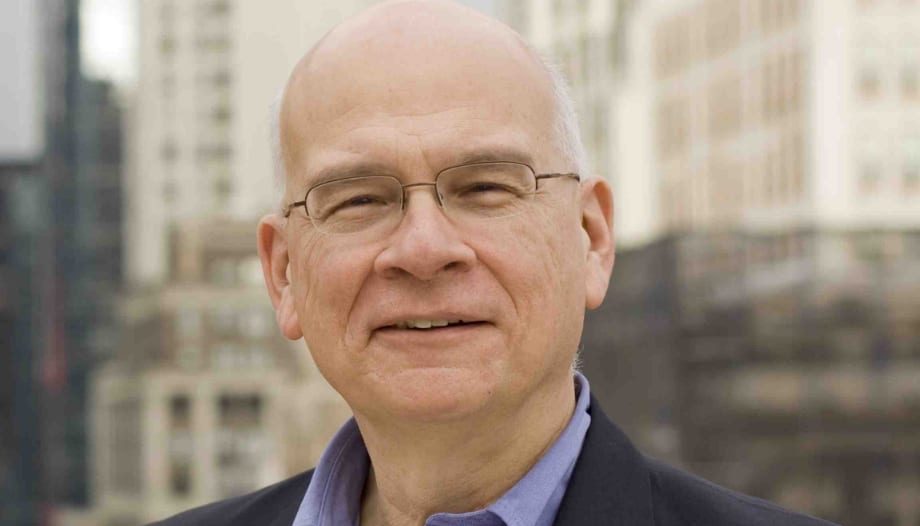

In a recent forum, “Conservative Christianity After the Christian Right,” Tim Keller predicted moderate growth of conservative evangelicalism even as the culture at large has grown more secular. In these remarks, he explains why these trends are leading to increasing polarization:

When I say “growing moderately,” I mean that the number of the devout people in the country is increasing, as well as the number of secular people. The big change is the erosion is in the middle. The devout numbers have not actually gone down that much. It depends on how you read them. But basically, they are not in freefall by any means.

You don’t so much see secularization as polarization, and what is really disappearing is the middle.

Keller sees the middle as having once leaned toward nominal Christianity, out of a sense of respect, tradition, or for social reasons. He says:

It used to be that the devout and the mushy middle — nominal Christians, people that would identify as Christians, people who would come to church sporadically, people who certainly respect the Bible and Christianity — the devout and the mushy middle together was a super majority of people who just created a kind of “Christian-y” sort of culture.

The mushy middle used to be more identified with the devout. Now it’s more identified with the secular. That’s all.

What does this mean for conservative Christians? Keller uses the analogy of an umbrella:

So what’s happening is the roof has come off for the devout. The devout had a kind of a shelter, an umbrella. You couldn’t be all that caustic toward traditional classic Christian teaching and truth. I spoke on Friday morning to the American Bible Society’s board. American Bible Society does a lot of polling about the Bible. The use of the Bible, reading the Bible, attitudes toward the Bible. They said that actually the number of people who are devout Bible readers is not changing that much.

What is changing is for the first time in history a growing group of people who think the Bible is bad, it’s dangerous, it’s regressive, it’s a bad cultural force, that was just never there. It was very tiny. And that’s because the middle ground has shifted, so it is more identified with the more secular, the less religious, and it’s less identified now with the more devout.

Later, he explains what the loss of this umbrella means for the devout:

The roof came off. That is, you had the devout, you had the secular, and you had that middle ground that made it hard to speak disrespectfully of traditional values. That middle ground now has not so much gone secular, but they more identified with this side. They are identified with expressive individualism, and so they don’t want to tell anybody how to live their lives.

And so what that means now of course is that the devout suddenly realize that they are out there, that the umbrella is gone, and they are taking a lot of flak for their views, just public flak.

He uses the White House’s rescinding an invitation to Louie Giglio as an example of the kind of flak conservative Christians are now experiencing:

And there was no doubt, by the way, the Louie Giglio thing, when he was sort of disinvited because of his traditional views on homosexuality from giving the invocation at the Inauguration, that was so clear. No matter how I add it up, I look at the mainline churches and I take out the quarter that are probably evangelical, my guess is that 80 percent of the clergy of this country would have some reservations about homosexuality — 75, 80 percent, something like that.

But what we were being told was that you are beyond the pale, not just that you’re wrong, but that respect for you is wrong. And so that was heard loud and clear in the conservative Protestant world. Loud and clear. It was enormously discouraging. It was sort of a sense of it’s not just that you’re going to disagree with us, but basically you are saying we really don’t even have a right to be in the public square.

So when you have, on the one hand, that kind of pushback in the public square because now the middle is with the secular rather than with the devout, you have both — more people from conservative Protestantism trying to get into the cultural industries than ever before, instead of just staying out and being in their own subculture; on the other hand, getting more pushback for their views than ever. What will happen?

I would think if you were in the media you would say this is a story, and I’m just going to have to keep an eye on it. Right now there is a tension between people wanting influence and people wanting to have less influence. And the end result is in doubt.