As Amos 7:14 says, “I am not a prophet or the son of a prophet.” I do not know who will win the presidential election, and even though I’m fascinated by various data points and pundit analyses that lay out different paths to either candidate’s victory, and even if I have an inkling as to how things will turn out, you won’t see me leaving my lane in order to make public predictions about who will be in the White House come January.

But there is something I can predict with nearly absolute certainty. Many Americans will be terribly and totally shocked by the election results.

Why?

- Because fewer and fewer Americans live in communities or have close friendships with people who vote differently than they do.

- Because fewer and fewer Americans trust the polls and surveys that signal the state of the race.

- Because social media algorithms exacerbate and reinforce pre-existing political impressions.

‘The Big Sort’

Over the past few decades, Americans have increasingly self-segregated politically, to the point that now most Americans live in “landslide counties,” where the people in their area vote overwhelmingly in favor of one candidate or the other. As a result, many Americans get the impression that their preferred candidate is not only winning, but dominating.

Bill Bishop, in a book written with Robert Cushing, calls this “the Big Sort.” They observe Americans becoming more and more polarized as each election passes, in part because “landslide counties”—where a candidate receives upwards of 20 percent or more of the vote—have become the norm in both rural and urban America. In other words, many Americans live not in red and blue counties anymore, but in super red and super blue regions.

David Wasserman writes in reference to the 2016 election:

“If you feel like you hardly know anyone who disagrees with you about Trump, you’re not alone: Chances are the election was a landslide in your backyard.”

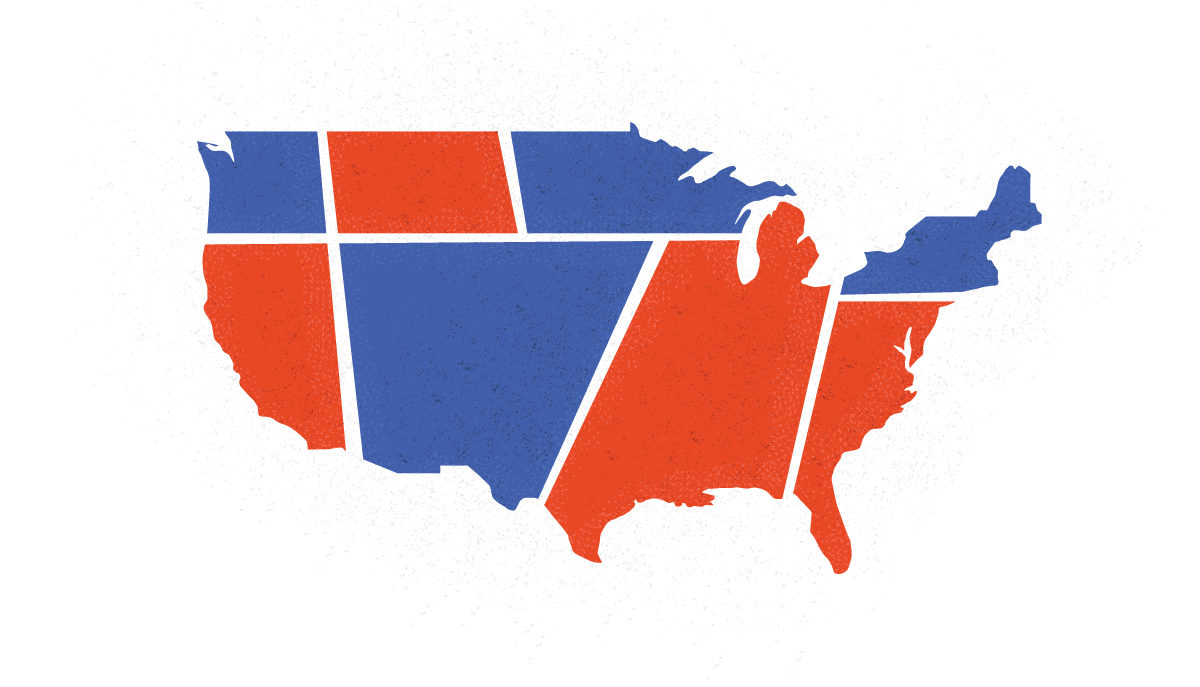

Here’s what the map looked like in 2016:

- “Of the nation’s 3,113 counties (or county equivalents), just 303 were decided by single-digit margins—less than 10 percent. In contrast, 1,096 counties fit that description in 1992, even though that election featured a wider national spread. During the same period, the number of extreme landslide counties — those decided by margins exceeding 50 percentage points—exploded from 93 to 1,196, or over a third of the nation’s counties.”

This trend is likely to continue, and the effects may intensify as many businesses shift to working remotely.

“Both liberals and conservatives . . . show a tendency to want to migrate to communities where they would fit in better,” Alan Greenblatt says in a conversation about migration studies and how Republicans and Democrats end up living apart.

Online Sorting

It’s not just true of our geographic location. Our online preferences reinforce the “big sort.” Consider the LifeWay Research and ERLC Civility study that shows 48 percent of evangelicals by belief agree that they “prefer to follow or befriend people on social media who have similar thoughts on social and political issues.” That’s not surprising, as people generally befriend others with similar interest and outlook.

But consider this statement about one’s preferred way of getting news: 53 percent agree with the statement, “I trust news more if it is delivered by people who have similar thoughts on social and political issues as me.” In other words, more than half of evangelicals prefer news sources that are partisan. Again, not surprising, as most people would rather have their worldviews confirmed than challenged.

Unfortunately, the result is a myopic and distorted view of reality. We are left with impressions from Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter delivered up by algorithms that create a narrative that may be far from the truth. The Trump supporter sees video after video of large campaign rallies, Biden’s frequent gaffes, and anecdotal evidence or selective bits of data that point to a huge upset on Election Day. The Biden supporter sees video after video of Trump saying something demeaning or silly, celebrity endorsements for the Democratic candidate, and data points that signal a landslide Biden win.

Knowing that 74 percent of evangelicals are on Facebook at least a few times a week (according to this study), and knowing how these algorithms and filters work to tailor our feeds to our preferences, it’s easy to see how those who spend time not only with their neighbors but also online are likely to feel confirmed in their belief that their candidate just couldn’t possibly lose. These habits fuel conspiracy theories and make more plausible the idea that the election must be rigged (and both Republicans and Democrats have openly entertained different versions of this theory).

Brace Yourself

For these reasons, we can expect that many Americans will be shocked next week. Both geographically and digitally, we have self-segregated into likeminded enclaves where we rarely deal substantively with people who hold different political perspectives.

How should the church respond? What can Christians do?

First, we must remind ourselves that our King is not up for election, that our faith is global not national, and that politics—while important—is not ultimate. In other words, we lift up the prominence of King Jesus in our thinking and demote the politics of this world. We are to engage in the political process out of love for neighbor, not out of fear or anger. We vote, we serve, we participate, but we do so as exiles and sojourners, not as people who pin all our hopes to any party or politician.

Second, it’s possible that churchgoing evangelicals are more likely than other Americans to come into contact with people with different political beliefs. Furthermore, 58 percent say that “they have someone they would consider a close friend who differs from them in having a very different political view.”

This means the church has a grand opportunity: to show a watching world what a community looks like where allegiance to Christ transcends the political differences of the current moment. We can push back against the trend of making nearly everything in life political, and of reducing people to their political views.

The commission we have from our King that does not distinguish between party affiliation. We are called to make disciples—and not only of Republicans or Democrats or independents. We cannot be satisfied with the enclave of our “landslide county” if we are faithful to our calling to lift high the glory of Jesus.

So, whatever happens on Election Day, don’t be shocked. Be settled. Firm in your faith. Kind in your convictions. Gracious in your words. Generous in your actions. We belong to a community that believes there’s no election shock and surprise that compares with Easter morning.

If you would like my future articles sent to your email, please enter your address.