There seem to be no stones left unturned in the life of C. S. Lewis. We even have his diary from his early to mid-20s in print, published as All My Road Before Me. I think most of us would cringe at the notion of inner thoughts from our young adult years being made public. Can the man have no privacy?

In addition to all of Lewis’s books—those he planned to publish and those he didn’t—we have stacks of collected correspondence he wrote over his lifetime. We even have Lewis’s letters in other languages, like those penned to a priest who’d read the Italian translation of The Screwtape Letters. Since Lewis didn’t know conversational Italian, and since the priest didn’t know English, they exchanged letters in Latin; these are now available as The Latin Letters of C. S. Lewis.

Becoming C. S. Lewis (1898–1918), Volume 1: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis

Poe, Harry Lee

Becoming C. S. Lewis (1898–1918), Volume 1: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis

Poe, Harry Lee

We have his books, his diary entries, his letters—what more could there be for us to squeeze out of Lewis’s life? We also have scads of biographies, some written by close friends, and many written by careful students of his life and writings—most recently the excellent work by Alister McGrath. Why another book on Lewis?

The answer is, we don’t need another book on Lewis.

That is, we don’t need another book on Lewis if we have the time and means to pour through the countless pages written by and about him, or to travel to Oxford or Wheaton to view the wealth of his unpublished materials. The challenge is even more daunting for someone wanting to explore Lewis’s childhood. Such obstacles make Harry Lee Poe’s Becoming C. S. Lewis: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis (1898–1918) not only interesting and helpful, but also necessary.

In Search of Aslan

Most books about Lewis—including his book about himself, Surprised by Joy—give few details about his formative years. After he published that spiritual autobiography, his friends joked a better title would be Suppressed by Jack. For those who have come to love his writings, an intimate picture of him as a boy and a young man is an invitation into the uncharted world that leads to Narnia.

This is the world about which Poe became increasingly inquisitive. Though curiosity is said to kill the cat, in this case, it led to a search for a lion. Lewis’s imagination has helped readers through the years better understand reality: Becoming C. S. Lewis gives us the story of its formation. It’s a world worth exploring, and Poe does it well.

Knowledge of the little things, the peculiarities and preferences of another, is a defining feature of a good friendship. That’s why Poe wanted to learn more of Lewis as a boy—to better understand him as an adult. This search led Poe to realize the extent to which the “early life of C. S. Lewis had been neglected”:

[Lewis] expressed opinions in those letters, before he went off to war, that he might have included in any of his scholarly works. It also became clear that most of the things he liked and disliked had been settled by the time he was 17. It became clear to me why Lewis devoted so much of Surprised by Joy to his school days and his time with Kirkpatrick. As I read the letters, this book began to take shape in my mind.

While Lewis’s diary from his 20s is called All My Road Before Me, Poe was interested in all the road behind him. The more Poe read in Lewis’s letters, the more the need for Becoming C. S. Lewis became clear. “I had never planned to write this book,” Poe says, “but it got ahead of me.” I’m thankful it did.

Essential Resource

Like McGrath’s biography, Poe takes into account all of Lewis’s letters and diaries, setting both his and also McGrath’s projects apart from earlier biographical works. Poe’s book is divided into nine chapters, beginning with Lewis’s birth and ending in 1918 with the soldier Lewis, an atheist, lying in a hospital bed recovering from wounds received in the Great War. The ground Poe covers in between sets the framework for the later accomplishments of the Oxford professor.

Becoming C. S. Lewis can be illustrated with a Texas oil field. From the interstate, you could make out the general landscape and topography. That’s how most books about Lewis deal with his childhood events—from a distance, moving rather quickly. However, Poe’s book drills down deep into many of Lewis’s early experiences, and he regularly strikes oil. Having read a lot by and about Lewis, I still made notes in the margins, underlined sections, and dog-eared pages for quick recovery.

As with any relationship, however, some may not need or care for a thorough analysis. Sometimes it’s enough to drive past the field and appreciate the panoramic. But for anyone wanting to explore, Poe’s book is an essential resource to understand Lewis’s personal and professional accomplishments in light of their embryonic origins. For sightseeing in the terrain of Lewis’s childhood and adolescence can help us better understand the man. These early years outline the “values, the longings, and the questions” that frame the intellectual path toward faith walked by Lewis the adult. But like pictures from one’s childhood, this is something reserved for those who want an intimate picture of the British apologist. Odd it would be to force one’s baby pictures on a stranger.

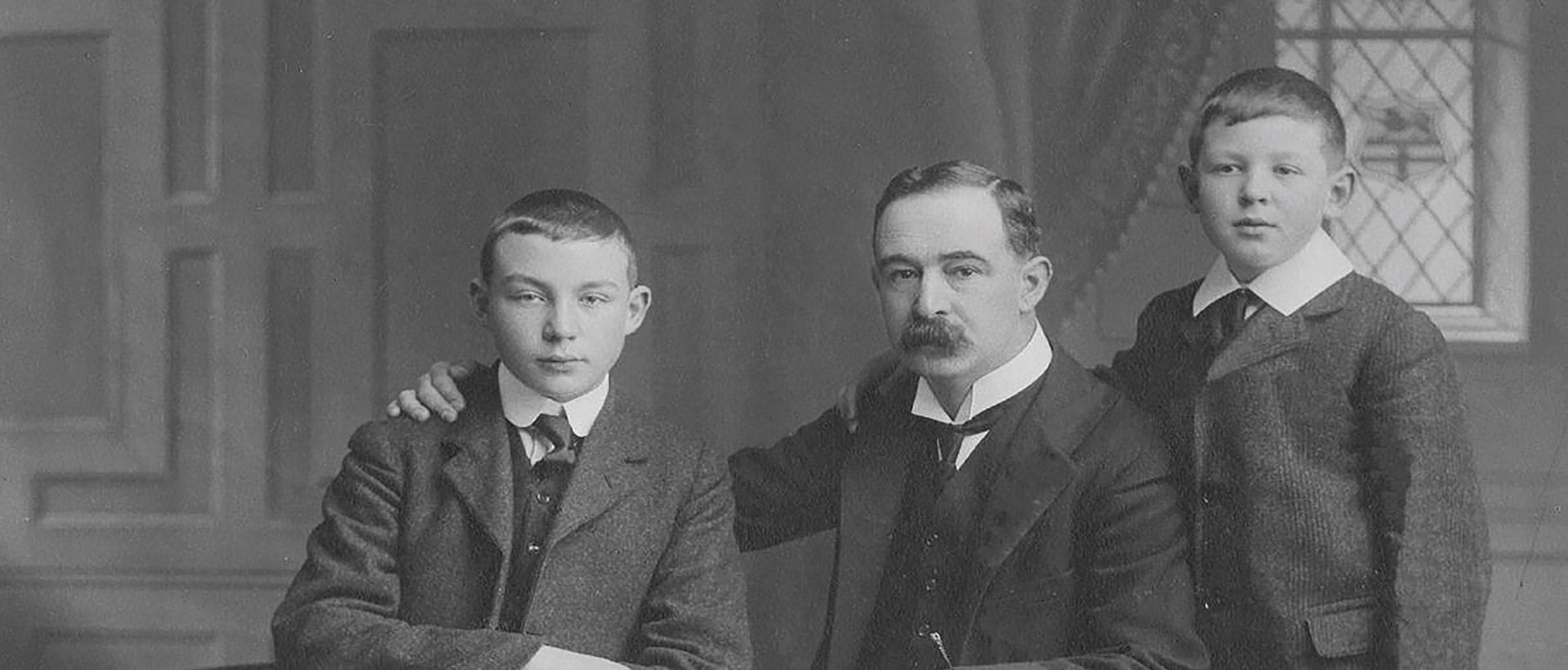

Still, in Lewis’s childhood we find a world of talking animals that predates Aslan. The young C. S. Lewis and his brother called it “Boxen.” In many ways, this youthful invention evolved into Narnia, home to a talking faun, a majestic lion, and an image of sacrificial love that’s left an indelible mark on the imaginations of millions. Anyone wanting to learn more about the childhood genius that in maturity brought us so much beauty should consider reading Becoming C. S. Lewis. In it, Harry Lee Poe takes readers through the wardrobe and into the world of a boy from whom so many worlds have come.