Matthew Levering—a Roman Catholic theologian who teaches at the University of Saint Mary on the Lake in Illinois—has a number of books to his credit. His newest book, Was the Reformation a Mistake? Why Catholic Doctrine Is Not Unbiblical, was written at the invitation of Zondervan. Levering offers an introduction then nine chapters on the following doctrines: Scripture, Mary, the Eucharist, the seven sacraments, monasticism, justification and merit, purgatory, saints, and the papacy. Each chapter consists of two parts, “Luther’s Concern” and “Biblical Reflection.” A lengthy response by Kevin Vanhoozer, titled “A Mere Protestant Response,” closes out the book.

On the first page of the introduction, Levering gives his answer to the book title’s question: “I do not call the Reformation a mistake,” (15, all page references to advanced reading copy). He adds that he’s grateful for many of the Reformation’s theological emphases. He contends, however, that “the [r]eformers made some doctrinal mistakes” (15).

In his rebuttal of the reformers, with Luther as the main focus, Levering seeks to show Roman Catholic doctrine is “not unbiblical.” It’s worth noting that isn’t the same as being biblical. It’s also worth noting Levering’s theological method or, as he puts it, his “mode of biblical reasoning.” He writes, “Rather than presenting his twelve disciples with a list of doctrinal truths, the Lord Jesus made clear that his disciples would need to learn the truth about him in a communal and liturgical way, by living with him over a period of time and by being intimately related to him” (21).

Was the Reformation a Mistake? Why Catholic Doctrine Is Not Unbiblical

Matthew Levering

Was the Reformation a Mistake? Why Catholic Doctrine Is Not Unbiblical

Matthew Levering

He further speaks of a “liturgically situated mode of reasoning about the realities described in the Bible” (25), adding that “the Holy Spirit may guide the church in Spirit-guided modes of biblical reasoning” (27).

Reasoning on Doctrine

This mode of reasoning is immediately pursued in chapter one on Scripture. Levering posits that “the church is the faithful interpreter of Scripture” (35), adding that if the church fails in being faithful, then “Scripture itself would fail in its truth” (35). Of course, for Levering the Bible can’t fail so, therefore, it must be true that the church can’t fail as interpreter. Levering does admit that church leaders err, but he maintains they are “preserved . . . from an error that would negate the church’s mediation of the true gospel to each generation.”

Now the reader can decide. Was Luther making a mistake at the Diet of Worms in 1521 when he claimed popes and councils may err and that his conscience was captive to the Word of God? Levering needs to reconcile his pronouncement of de facto gospel fidelity on behalf of Rome against the data of the 16th century (and other centuries for that matter).

Would Levering endorse the systemic abuse of indulgences as practiced in the church at the time of the Reformation? The fact that Levering doesn’t address this challenge to his thesis in a book on the Reformation is a serious gap, if not a death blow to his argument. At the very least, this chapter demonstrates clearly the distinction between sola scriptura and the Roman Catholic view.

Levering then turns to eight Catholic doctrines. He makes the point that Mary’s suffering was “uniquely united with her Son’s suffering,” and from there asks, “Did Mary receive a unique share in his exaltation?” (71). He then employs “typological reasoning” to see Mary in many exalted roles and places—including as the “Queen Mother” in Jeremiah 13:18.

On the saints, Levering acknowledges that Paul uses saints to refer to all Christians, but then notes how Rome identifies certain individuals as “saints in a particular sense” (157). Levering ends the chapter by declaring, “To love the saints and to ask regularly for their prayers is to love Christ and the Father who sent him” (171).

On the papacy, he offers no attempt to show the evidence of apostolic succession from Peter onward. He simply states, “The form that this Petrine ministry takes in the church develops over the centuries under the guidance of the Spirit” (186). That’s not an argument; it’s a supposition. Given the role of the papacy in the Roman curia, Levering is going to have to do better.

Shared Gospel?

As important as these doctrinal differences are, the central issue is the gospel. At various points Levering speaks of Catholic and Protestant communion around the gospel, but such communion doesn’t exist. Regarding purgatory, Levering says, “Christ has paid the penalty of sin and has perfectly forgiven us, but we nonetheless must go through the penitential experience of suffering and death so as to be fully configured to him in love” (154). The “but” there is damning. The gospel is Christ’s finished work plus nothing, yet Levering here holds to Christ’s finished work plus something: extra suffering after death if life’s sufferings didn’t fully purify you.

But Luther’s fear wasn’t purgatory; he feared the final judgment on the last day. Purgatory is actually a distraction from the real threat to humanity: eternity in hell under the just wrath of God. Either Christ removed the curse from us and we’re reconciled to a holy God and will be with him at the moment of our death, or the curse isn’t removed and we’ll be separated from God in this life and forever. Purgatory isn’t only unbiblical; it’s an affront to the gospel.

In chapter six on justification and merit, Levering rejects imputation. He asks if it’s possible that “we are made truly just and not merely imputed to be just?” (133). This is a crucial distinction. If we’re made just, then we work with the grace God gives us, and our justification is a result of both God’s grace and our works. There could be no more crucial place for a distinction than between justification and sanctifciation. The doctrine of imputation is key to that distinction. Justification is apart from works, apart from merit—and apart from penitential suffering in purgatory.

Necessary Reformation

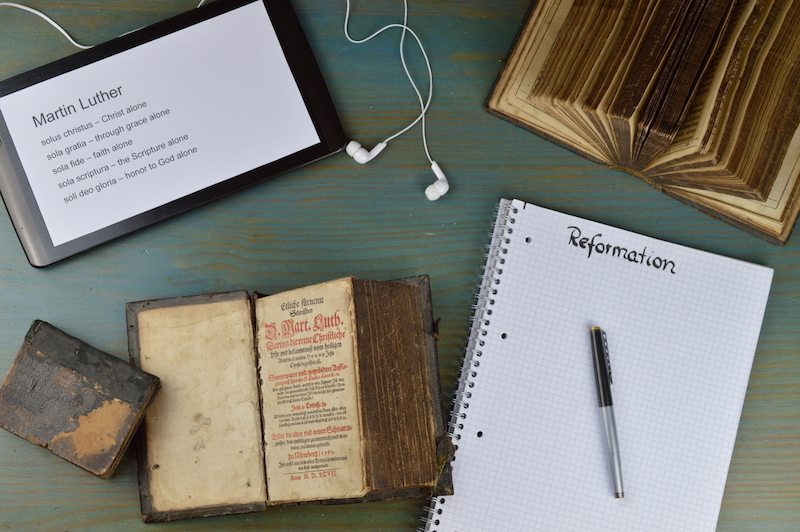

Was the Reformation a mistake? No, it wasn’t, for there are clear and crucial differences between Rome and the reformers on Scripture and the gospel, not to mention the other seven doctrines in this book. The reformers’ efforts centered around a formal principle and a material principle. The formal principle concerns the question of authority. The difference between the reformers and Rome on authority was crystalized at the Council of Trent. There Rome affirmed Scripture as authoritative as it is interpreted through Rome. Hence, we see the value of the sola in the Reformation view of sola scriptura.

The material principle concerns justification and how a person is redeemed by Christ and reconciled to God. The Council of Trent affirmed that we “cooperate with and assent to” grace for our salvation. Here again we see the value of sola in the Reformation planks of sola fide (faith alone) and sola gratia (grace alone). (By the way, Trent’s anathemas against the doctrine of justification by faith alone have never been retracted.)

Levering’s book does succeed in showing these real and clear differences between Rome and those who follow in the Reformation traditions—which is to say, his book succeeds in showing that the Reformation is still necessary.